KEY JUDGEMENTS

I. We assess that Russian intelligence staged the recent provocations in Transnistria as part of a military deception campaign (“maskirovka”). Russia aims to prevent Ukrainian forces in Odesa province from reinforcing positions in Donbas and Kherson.

II. The Transnistrian maskirovka is contingent and could escalate into more palpable operational objectives in the short term. While the Operational Group of Russian Forces in Transnistria (OGRF) is unfit to engage in significant combat, we cannot ascertain that Moscow will see the Group’s precarious condition as an obstacle to joining the fight. One possible scenario is that the OGRF could attempt to contest or seize the Palanca road segment of the Reni-Odesa highway – controlled by Ukraine although on Moldovan territory (Stefan Voda raion).

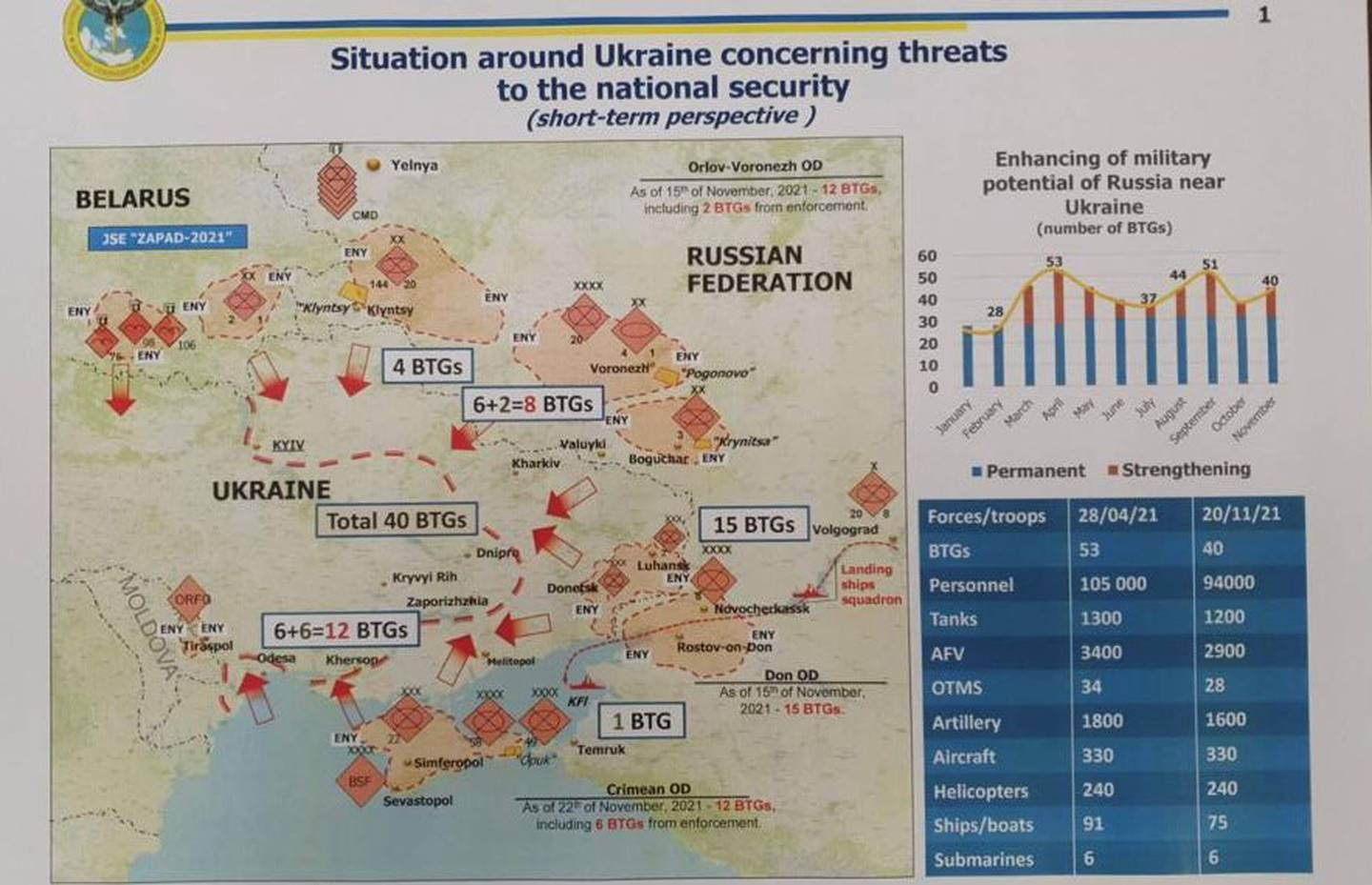

III. We assess that the Kremlin retains the intention of linking up with Transnistria, but the Russian military is operationally unable to reach this goal in the medium term. The vast majority of Russian battalion tactical groups (BTGs) are committed to Donbas and Kherson, where they are desperately needed, and continue to suffer a heavy attrition rate.

IV. We have threatcasted three notional scenarios that Russia might consider at any given time to link up with Transnistria:

- landbridge from Kherson to Transnistria (via Odesa);

- air assault into Tiraspol;

- amphibious landing in Budjak province followed by an incursion into Moldova’s Stefan Voda raion.

These scenarios are purely imaginative and do not aim to predict to future. Instead, their role is to reduce uncertainty.

SITUATION REPORT: RUSSIA ENGINEERS A POTENTIALLY MALIGN DISTRACTION

OGRF: THE FORGOTTEN “LITTLE GREEN MEN”

1. The self-proclaimed and unrecognized “Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic” hosts roughly 1,000 to 1,500 Russian soldiers as part of the Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF). The OGRF is the illegal Russian occupation force that remained after the 1992 invasion of Moldova. The OGRF is a direct successor to the locally-based Soviet 14th Guards Army, which served under the command of the Odesa Military District.

The OGRF consists of three units:

-82nd Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Battalion [unit 74273]

-113th Separate Guards Motorized Rifle Battalion [unit 22137]

-540th Separate Command Battalion [unit 89353]

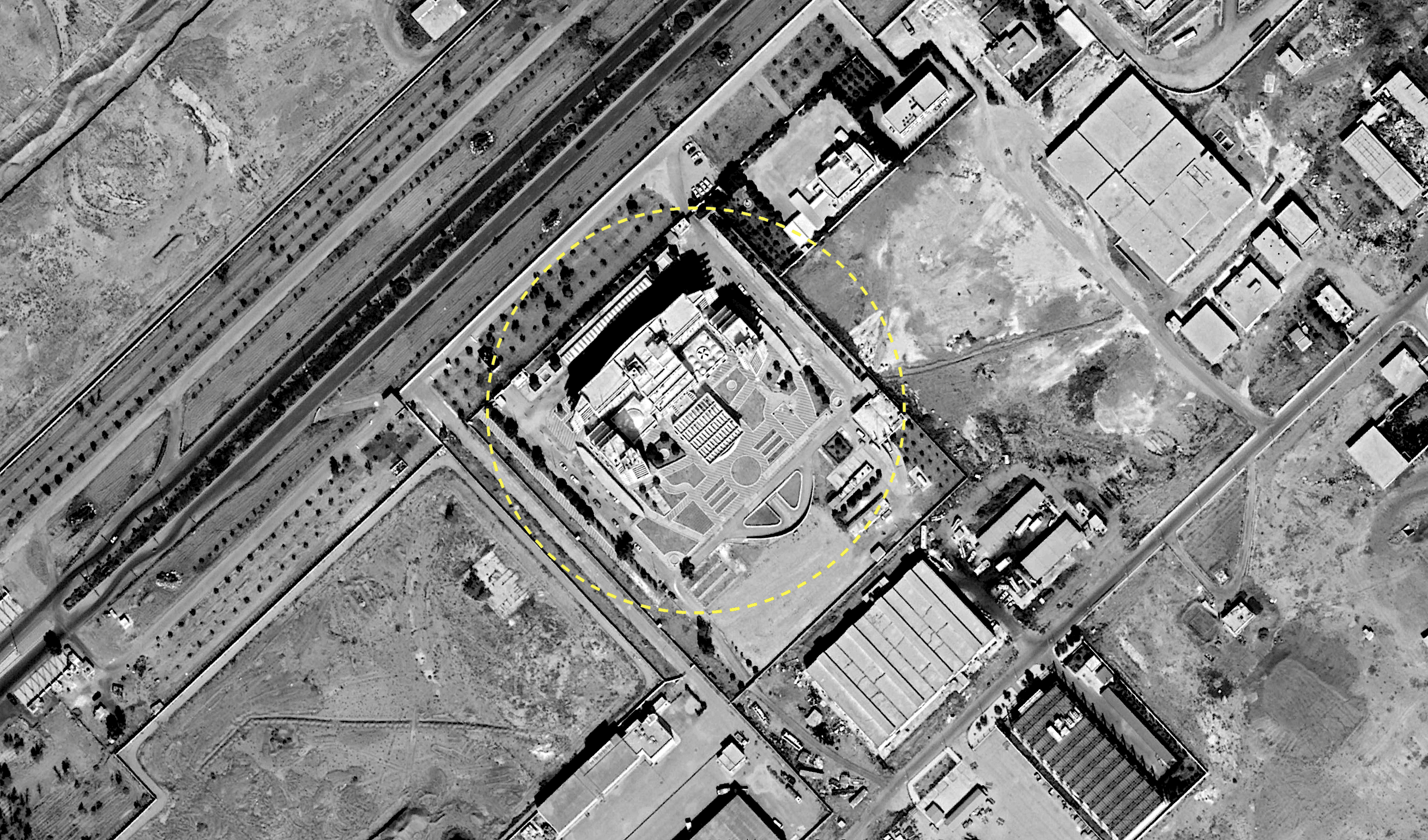

Together these three units could likely assemble only one battalion tactical group (BTG) – Russian Ground Forces’ (RGF) combined-arms formations for combat use. Based on our open-source research, all three OGRF units are headquartered at Karl Liebknecht 159, Tiraspol, Republic of Moldova. However, the units are most likely garrisoned elsewhere, as the Soviet-era military quarter has been largely abandoned and re-purposed into new apartment projects.

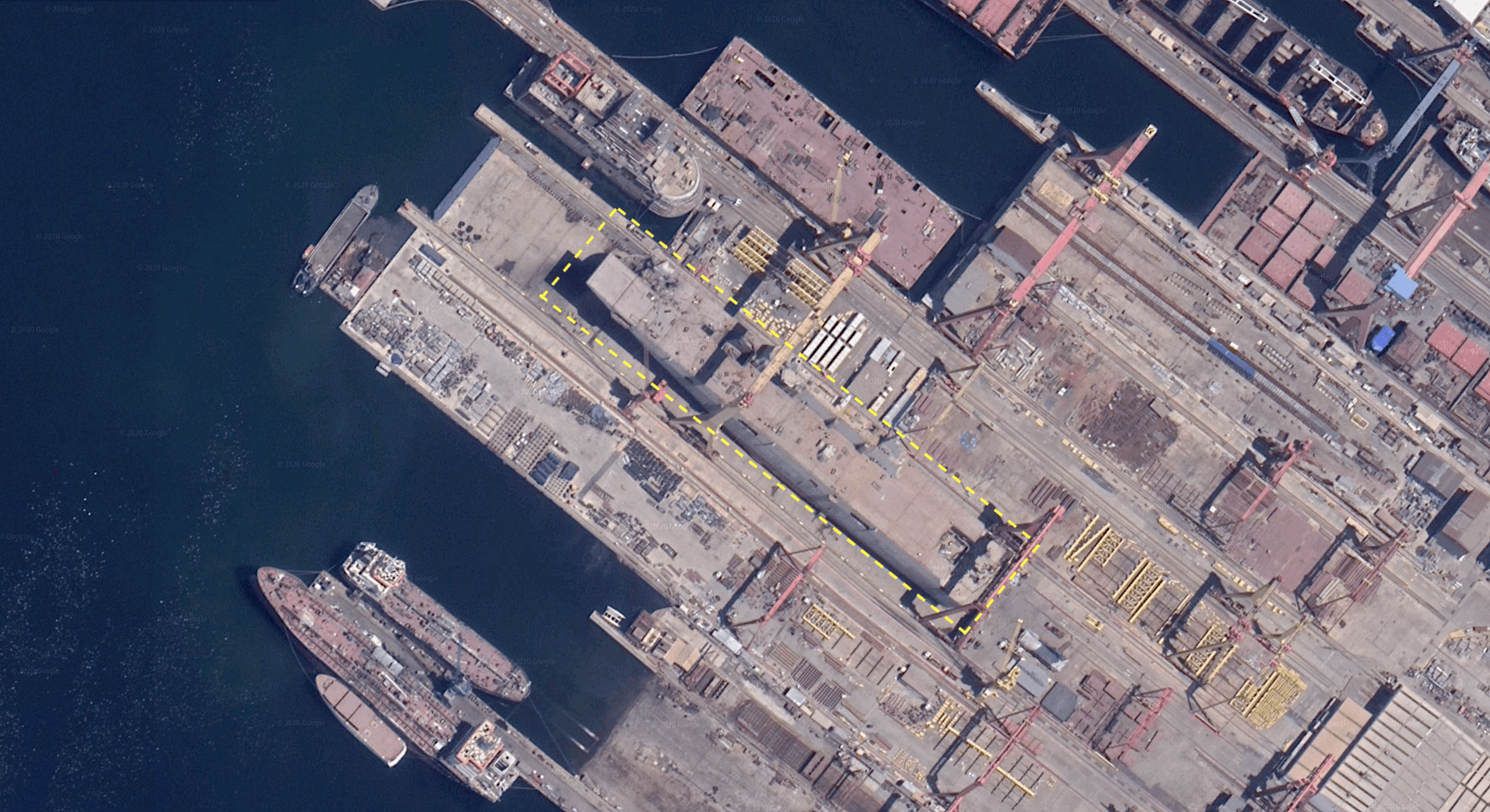

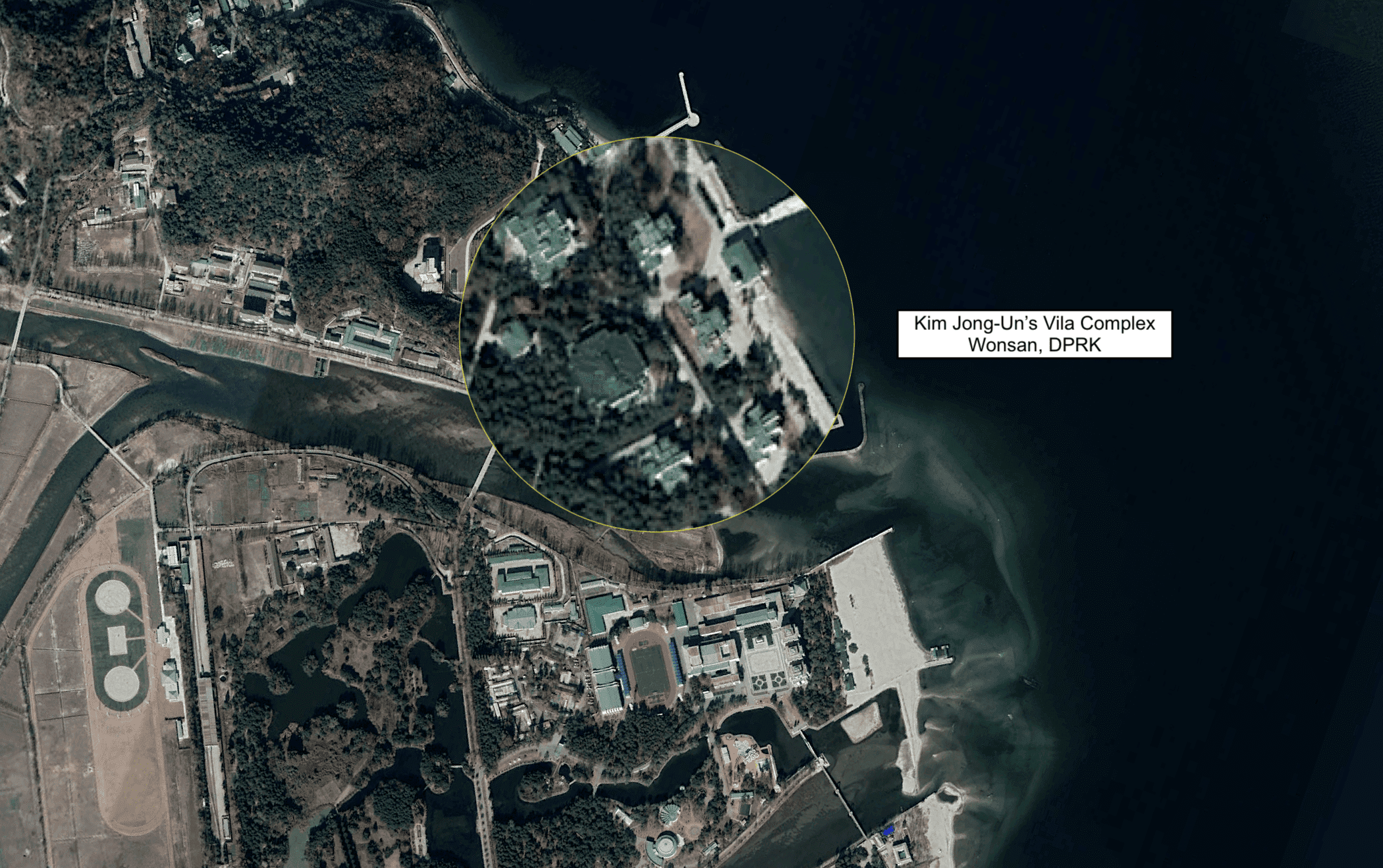

GEOINT: Overview of OGRF HQ and assessed affiliated sites in Tiraspol

2. The OGRF has three operational objectives in the region:

-Engage in capacity-building efforts;

-Guard ammunition storage sites in Transnistria, especially the Cobasna ammo facility.

-Serve Moscow’s interest in whatever way necessary.

3. While the OGRF is probably the most ill-equipped and undertrained force in the entire Russian Armed Forces, it does pose a serious threat to the Moldovan military and could become a tactical distraction for Ukraine.

MASKIROVKA: KEEP UKRAINIAN UNITS FIXED IN ODESA, AWAY FROM “REAL FIGHT” IN KHERSON, DONBAS

4. We assess that Russian intelligence staged the recent provocations in Transnistria as part of a military deception campaign (“maskirovka”). Russia aims to prevent Ukrainian forces in Odesa province from reinforcing positions in Donbas and Kherson. Russia’s remaining main lines of effort (LOEs) in the invasion are the Donbas offensive and consolidating gains in Kherson province. Ukrainian reinforcements in these theaters could put a decisive dent in Russia’s sluggish and largely unsuccessful operations.

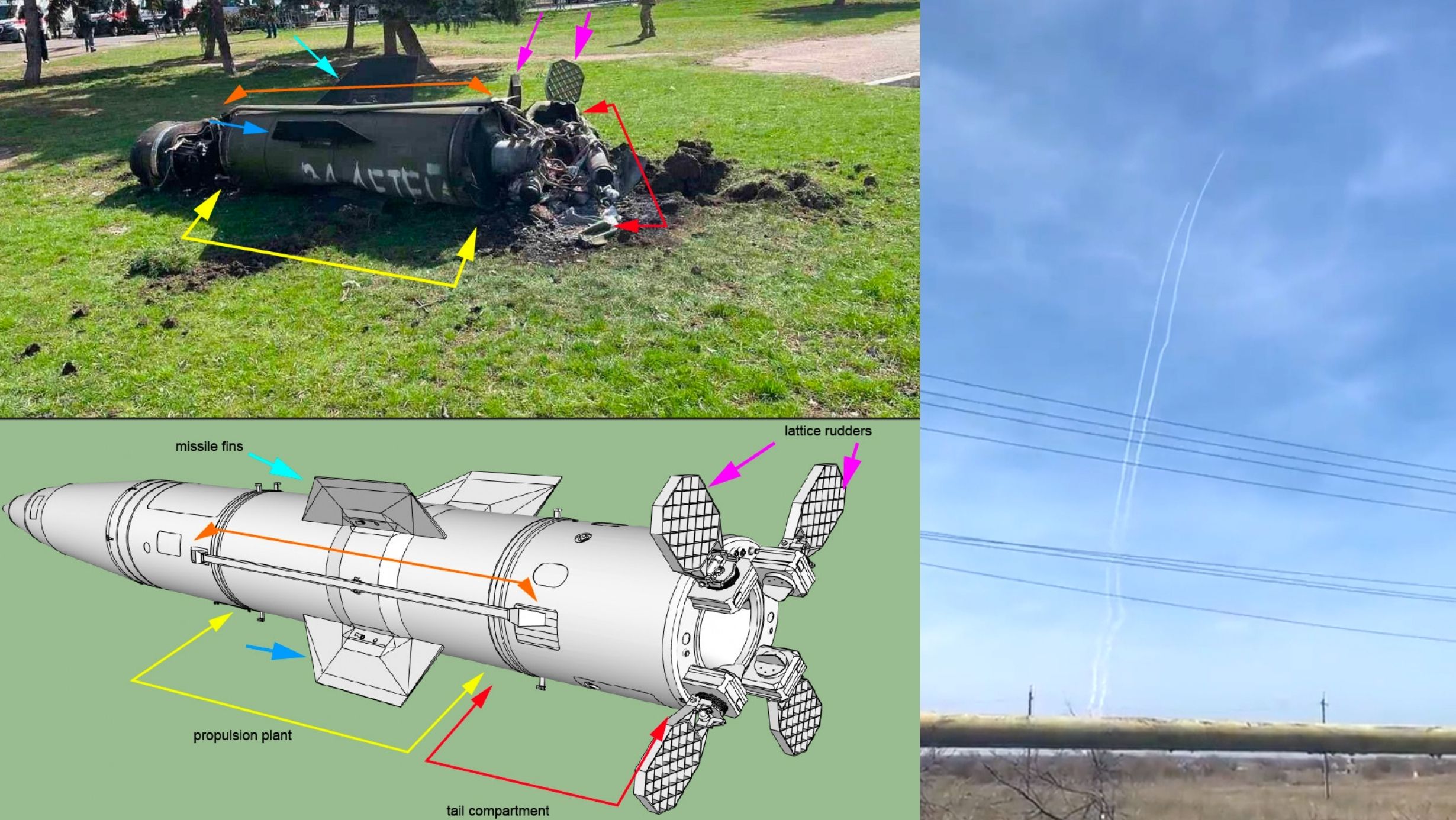

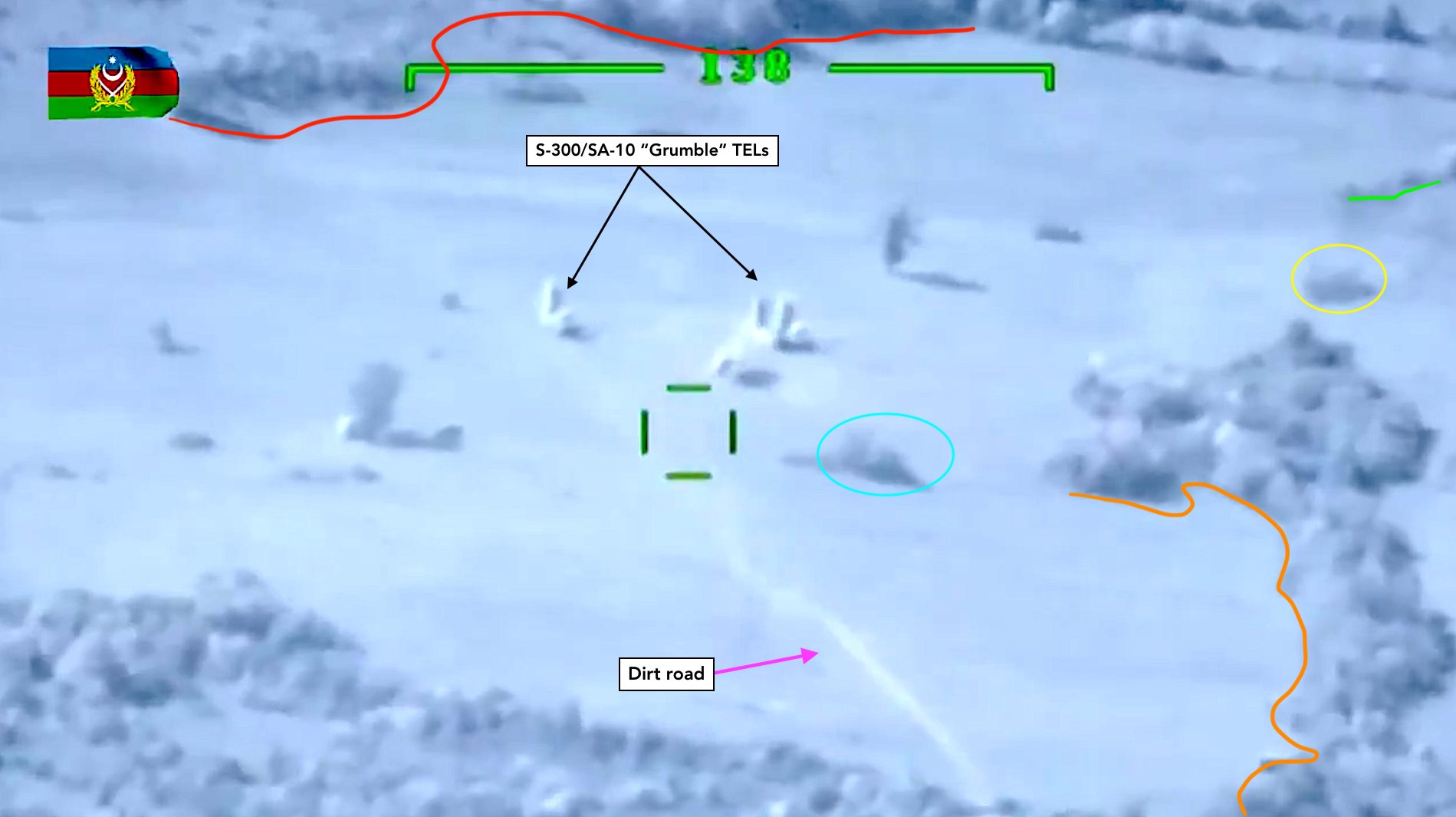

5. Russian intelligence most likely orchestrated a series of incidents in Transnistria:

- a rocket-propelled grenade attack on the so-called “Ministry of Security;”

- two destroyed antenna towers in Grigoriopol raion (used to broadcast Russian radio channels).

- claimed gunshots towards Cobasna village which hosts a Soviet-era ammunition depot.

- explosions at Tiraspol airfield (confirmed by Moldovan authorities).

- Reported explosions at a border crossing with Ukraine.

6. The “local government” responded by placing the Transnistrian military on high alert and ramping up anti-Romanian and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric. Moldovan and Ukrainian press outlets report that the Transnistrians have established checkpoints throughout the region (confirmed via social media photos), and are preparing for general mobilization (claim denied by the Transnistrian “authorities”). Tiraspol has placed its military on high alert according to the Ukrainian General Staff.

MASKIROVKA IS CONTINGENT, ESCALATION POSSIBLE

7. While the recent provocations constitute a benign feint, the OGRF’s maskirovka is contingent and could escalate into more palpable operational objectives in the short term. To craft a credible threat that will force the Ukrainians to divert attention to the Dniester river, the OGRF (with or without the Transnistrian military) could launch limited cross-border attacks. Alternatively, although less likely, the OGRF could launch a limited land incursion.

8. One possible scenario is that the OGRF could attempt to contest or seize the Palanca road segment of the Reni-Odesa highway – controlled by Ukraine although on Moldovian territory (Stefan Voda raion). Chisinau transferred the 7.7 km road segment near Palanca to Ukraine as per the Additional Protocol (AP) to the Treaty between the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine on the State Border (August 18, 1999). The two parliaments ratified the AP in 2001.

Palanca Road (T-Intelligence 2022)

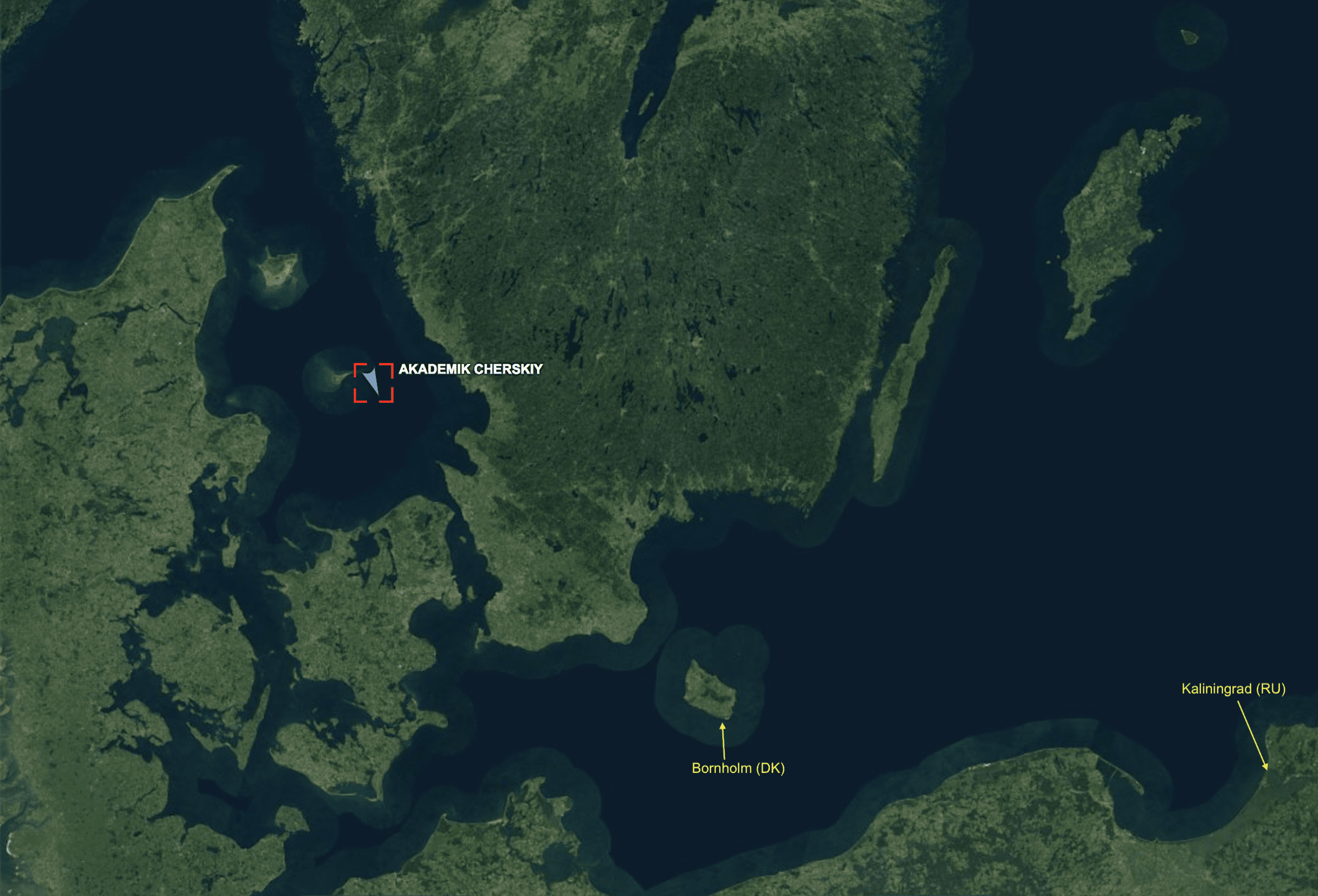

The Palanca road is now the sole remaining ground line of communication (LOC) between NATO member Romania and the eastern raions of Odesa province, as Russia bombed and damaged the Pidyomnyy bridge near Zatoka on April 26. The

Russia bombed the Pidyomnyy bridge for military and economic reasons. On the one hand, Russia wanted to disrupt the flow of Ukrainian products exported through the Romanian seaport of Constanta as Russia has blockaded Odesa and the other Ukrainian ports. On the other hand, with the bridge disabled, Russia severed NATO’s most direct LOC with Ukraine’s frontlines.

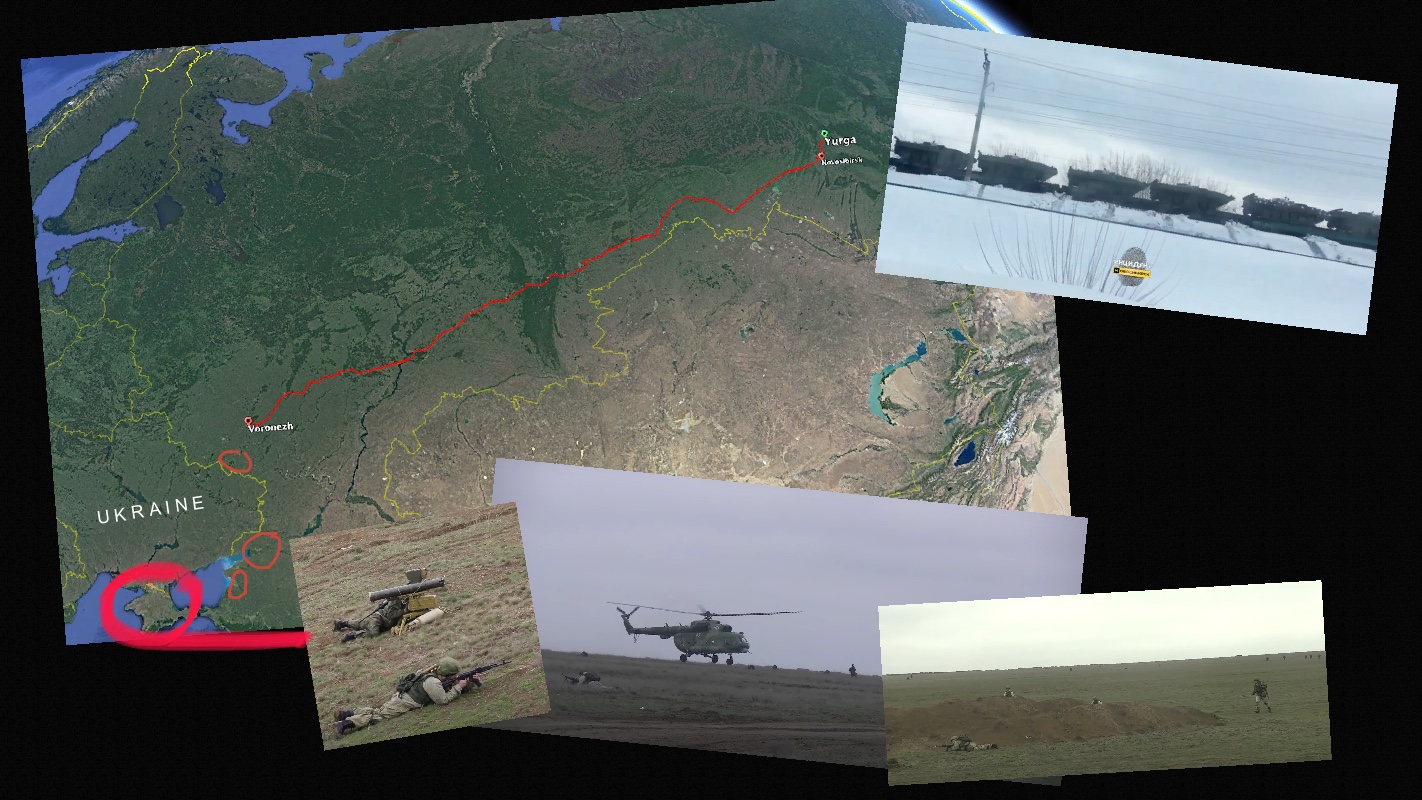

9. While the OGRF is unfit to engage in significant combat, we cannot ascertain that Moscow will see the Group’s precarious condition as an obstacle to joining the fight. Based on our estimates, Belarusian President Lukashenko’s war map, and other indicators, Transnistria was scheduled to join the now-failed Southwestern Operational Direction (OD). The OGRF and the Russian Southern Military District (MD) grouping would have linked up in the process.

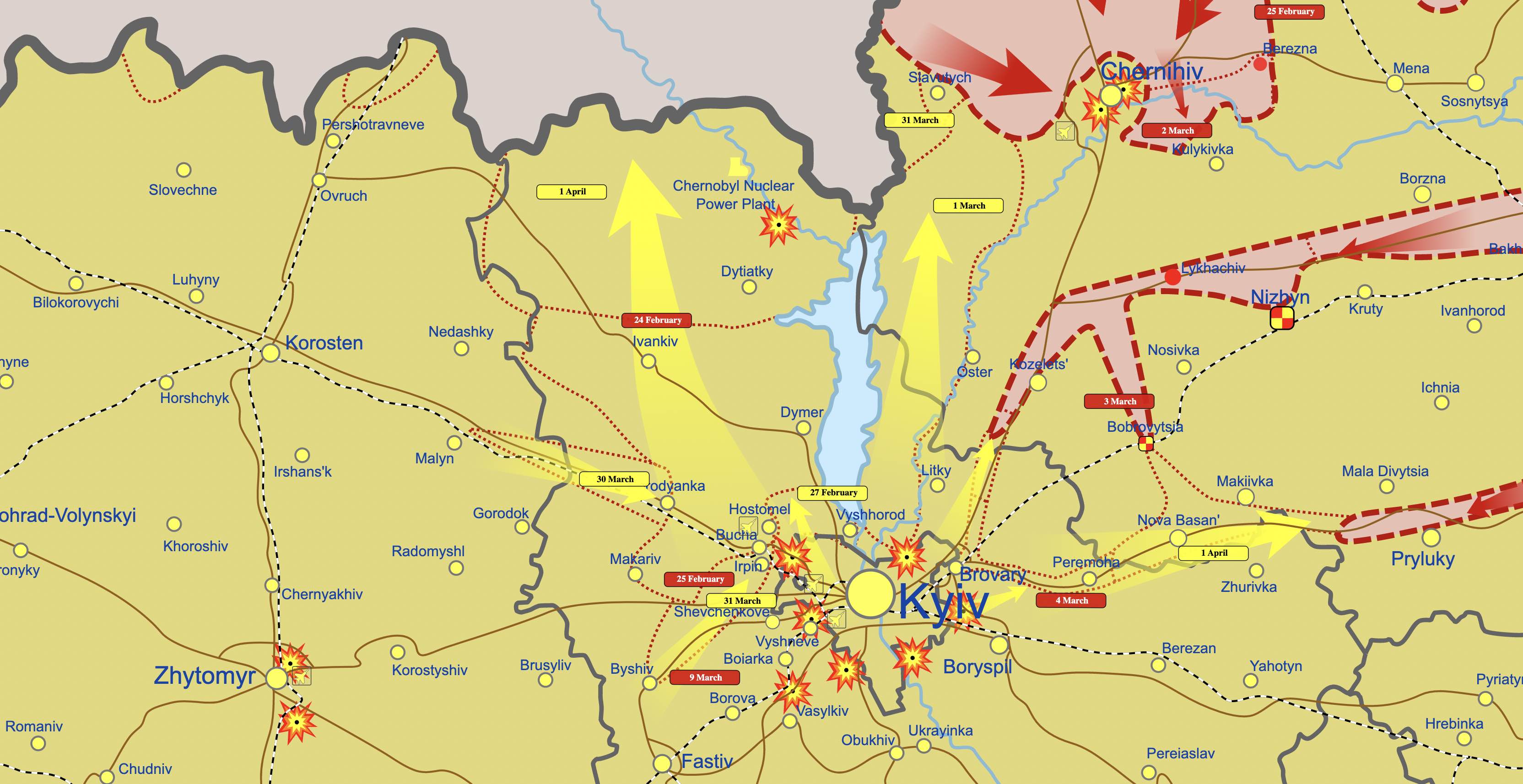

Transnistrian and Russian link-up to take Odesa is shown in Lukashenko’s warplan presentation (modified version of EyePress News/Shutterstock image)

RUSSIA-TRANSNISTRIA LAND-BRIDGE UNFEASIBLE IN NEAR TERM

10. We assess that the Kremlin retains the intention of linking up with Transnistria, but the Russian military is operationally unable to reach this goal in the medium term. Sandwiched between a pro-European & NATO-friendly Moldova (Maia Sandu government) and a hostile Ukraine, the OGRF is vulnerable to an attack. However, Russian BTGs are committed to Donbas and Kherson, where they are desperately needed, and continue to suffer a heavy attrition rate. A significant portion of BTGs is combat ineffective and close to collapse. Re-deployment will most likely not be an option. On its own, the OGRF is unlikely to be able to break through Ukrainian territory and spearhead a landbridge. The calculus could change if Russia declares a general mobilization and generates new manpower.

THREATCAST: THREE NOTIONAL SCENARIOS FOR A RUSSIA TO LINK UP WITH TRANSNISTRIA

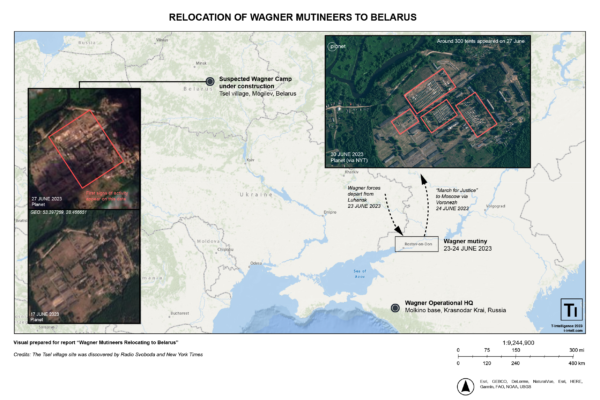

We have threatcasted three alternative future scenarios that Russia might consider to link up with Transnistria:

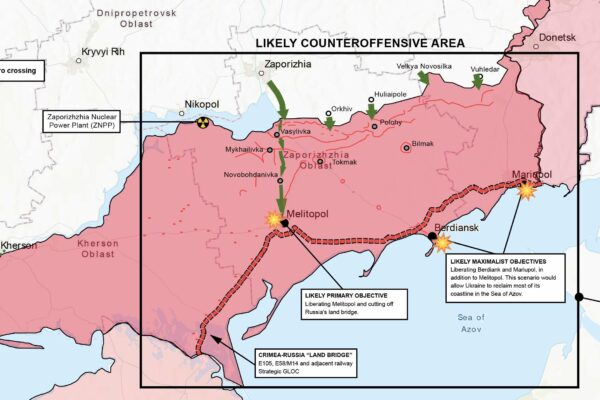

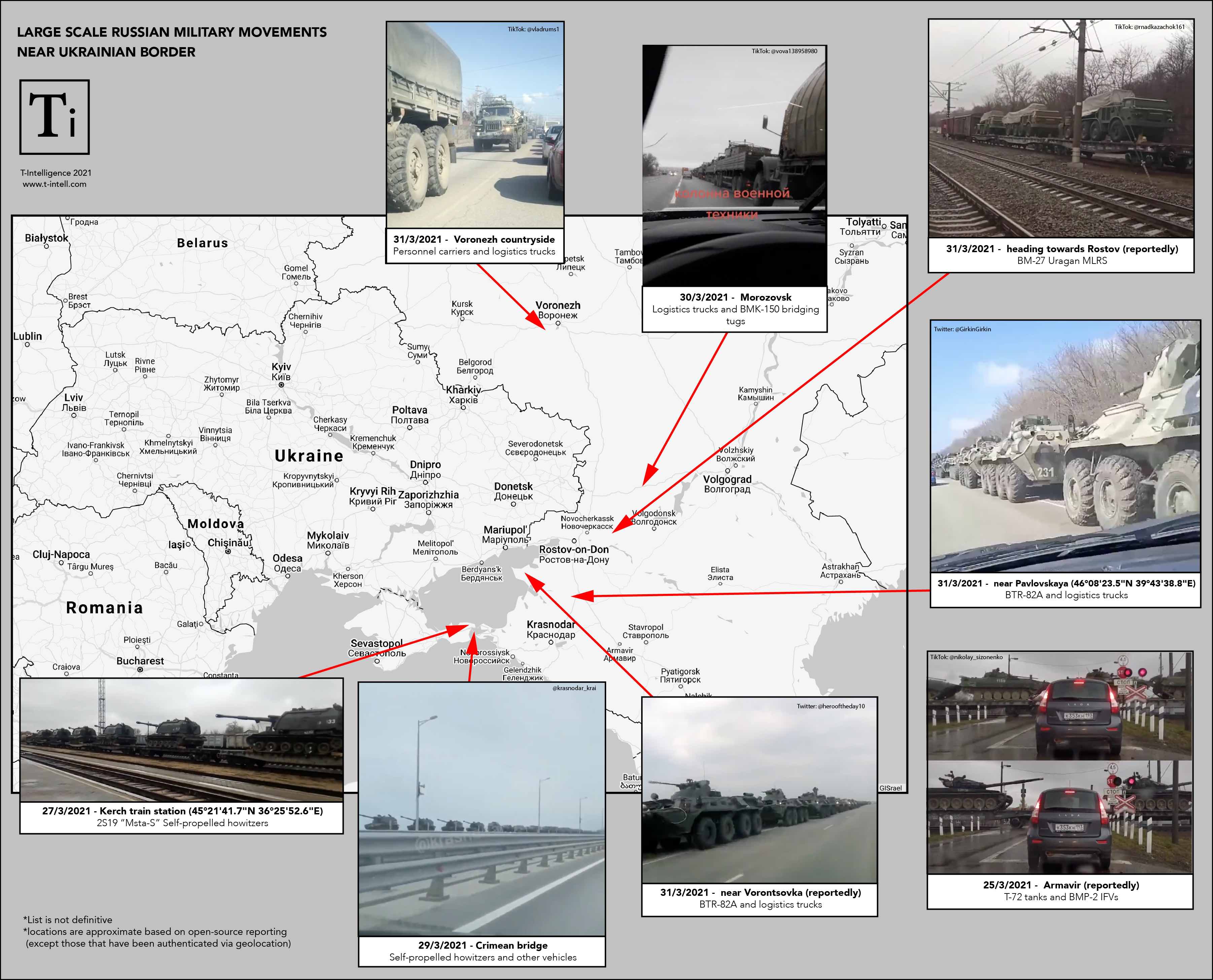

- Landbridge from Crimea to Transnistria (via Kherson-Mykolaiv-Odesa).

- Air assault on Tiraspol.

- Amphibious landing in Budjak.

Disclaimer: Please note that the following scenarios are speculative and present a loose snapshot of possible war plans. This threatcast aims to consider some, but not all, of Russia’s possible actions in Transnistria – caveats apply.

LAND-BRIDGE (TRIED AND FAILED)

11. This scenario looks at a land corridor from Crimea to Transnistria, drawing from Russia’s tried-and-failed Southwestern OD. Such an objective would require an extensive, multi-stage offensive that would be costly and grinding for Russia. However, for the sake of this exercise, let us consider the conditional victories for Russian forces to “shake hands” with the OGRF by land:

Scenario 1: Land Bridge via Odesa (T-Intelligence 2022)

a. Starting from Crimea-Kherson, Russia would need to isolate or capture Mykolaiv and cross the Bug river. Considering that Ukrainian forces would likely destroy the bridges to stall or stop the offensive, Russia would need to set up pontoon bridges in select areas while under fire from the opposite shore.

b. Once across the Bug, Russian forces would need to cross the Tylihul. If successful here, the Russians would secure their LOCs and ensure a steady flow of logistics across the two rivers.

c. Isolating or capturing Odesa would be the invading force’s next and most draining objective. Besieging Ukraine’s third-largest city – over 1 million people – would be a gargantuan effort in terms of time, resources, and manpower. From a humanitarian perspective, the brutal two-month siege of Mariupol would be a cakewalk in comparison.

d. The OGRF could join the fight as a support element and link up with the Russian forces around Odesa in the process. However, a successful land bridge would depend on the long-term control of the Kherson-Odessa corridor.

12. Russia has already pursued this blueprint and failed in the early stage of the Southwestern OD campaign – it cannot replicate it soon. Unable to capture Mykolaiv, Russia chose to (unsuccessfully) isolate the city and look for a gap in Ukrainian defenses up the Bug river valley. A small contingent of forces advanced to Voznesensk (March 3) in an attempt to take the city and cross the Bug. Fearing that a Russian victory in Voznesensk would greenlight the OGRF to open the second front, Ukraine blew up the railway bridge over the Kuchurhan river on March 4. After days of fighting, Ukrainian defenders crushed the Russian advance between March 13-16 and launched a counter-attack. Ukrainian forces chased the Russians down to Mykolaiv and ultimately drove them back to Kherson, where the Russian Southern MD grouping remains today. Given the premature failure, the OGRF was never called up to assist.

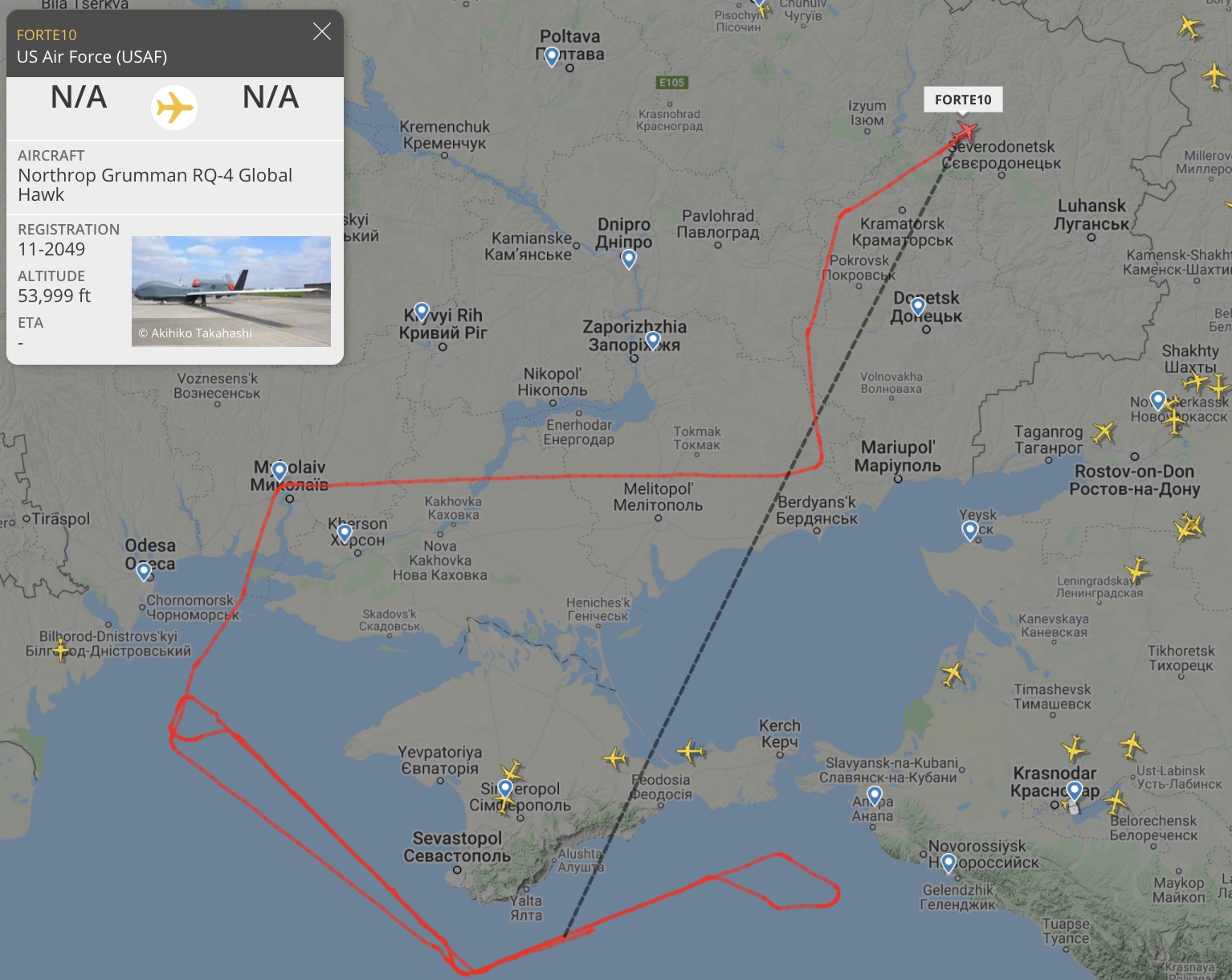

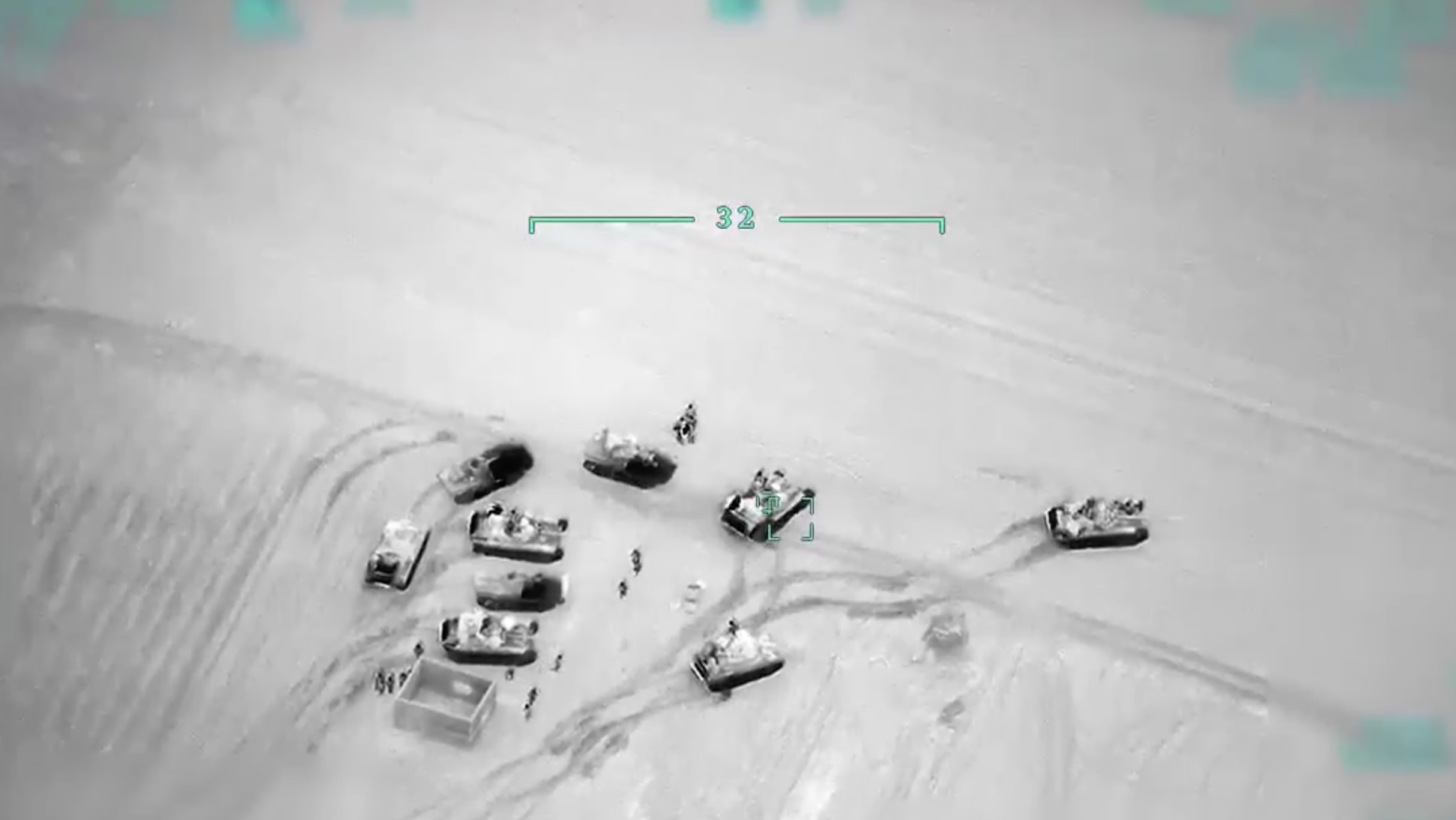

AIRBORNE ASSAULT ON TIRASPOL

13. Link-up with the OGRF via airbridge is possible, although the operation would have a low-probability of success (LOS). The Russian Air Assault Force (Vozdushno-desantnye voyska Rossii/VDV) would spearhead the mission supported by rotary-wing units from the Russian Aerospace Forces (RuAF) to airlift troops and equipment such as BTRs, artillery, and rocket launchers. Airfields in Crimea and Kherson are possible embarkation points, while Tiraspol airfield is the projected end destination. Infiltration routes are of two categories – through denied airspace or around it – posing a wide array of issues and hazards.

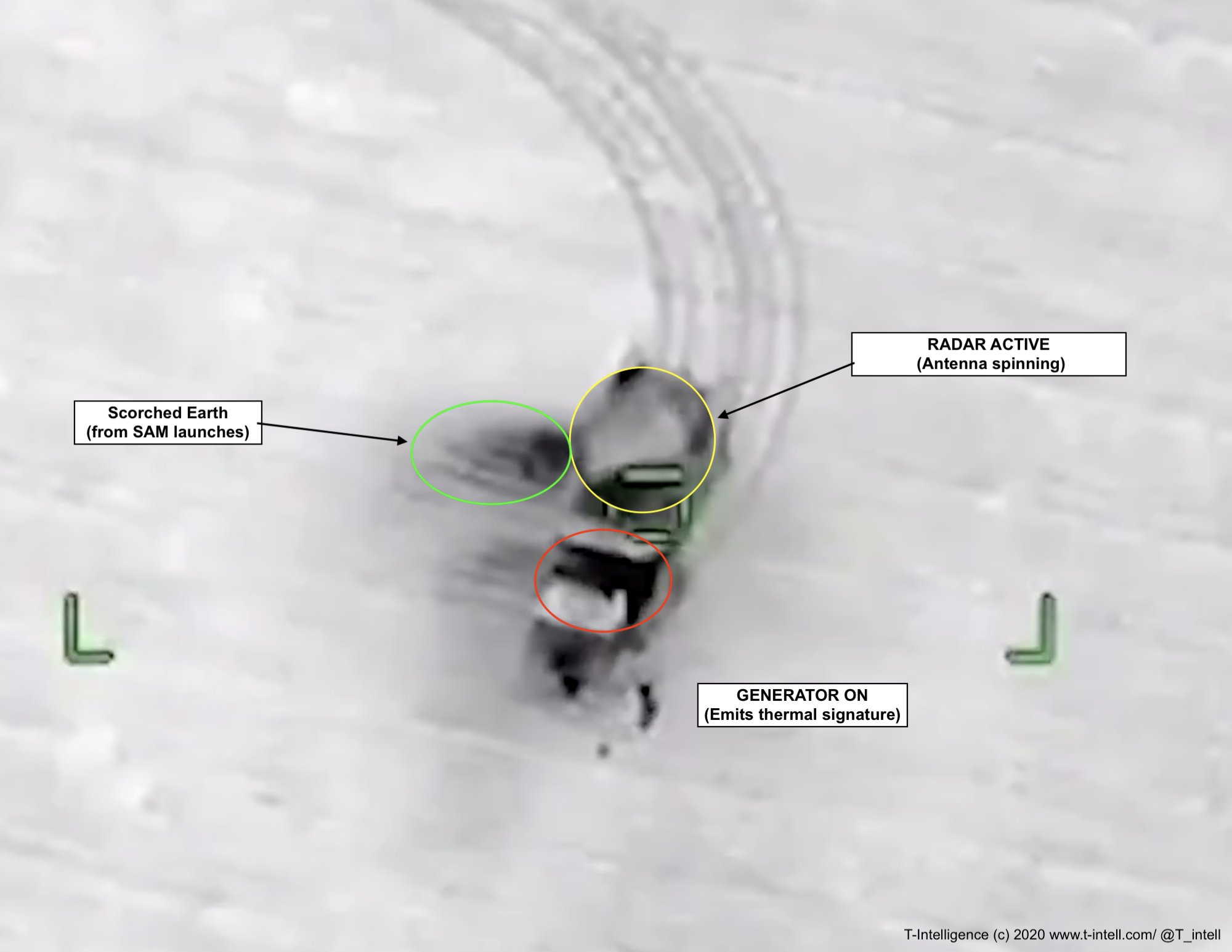

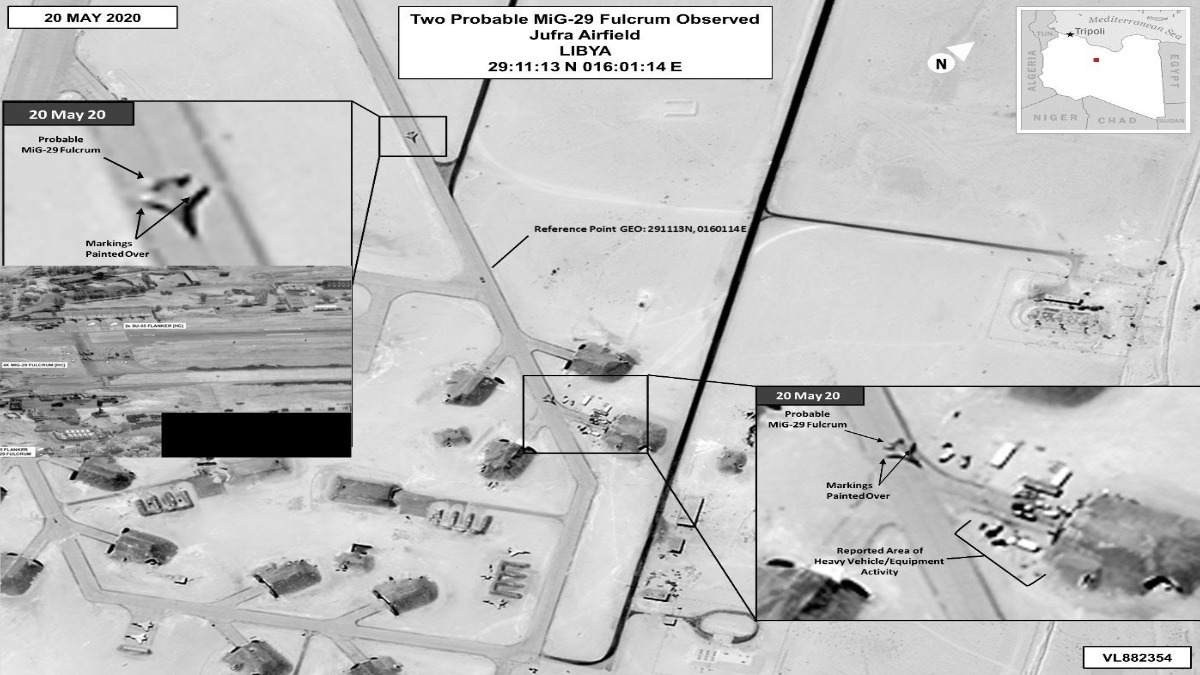

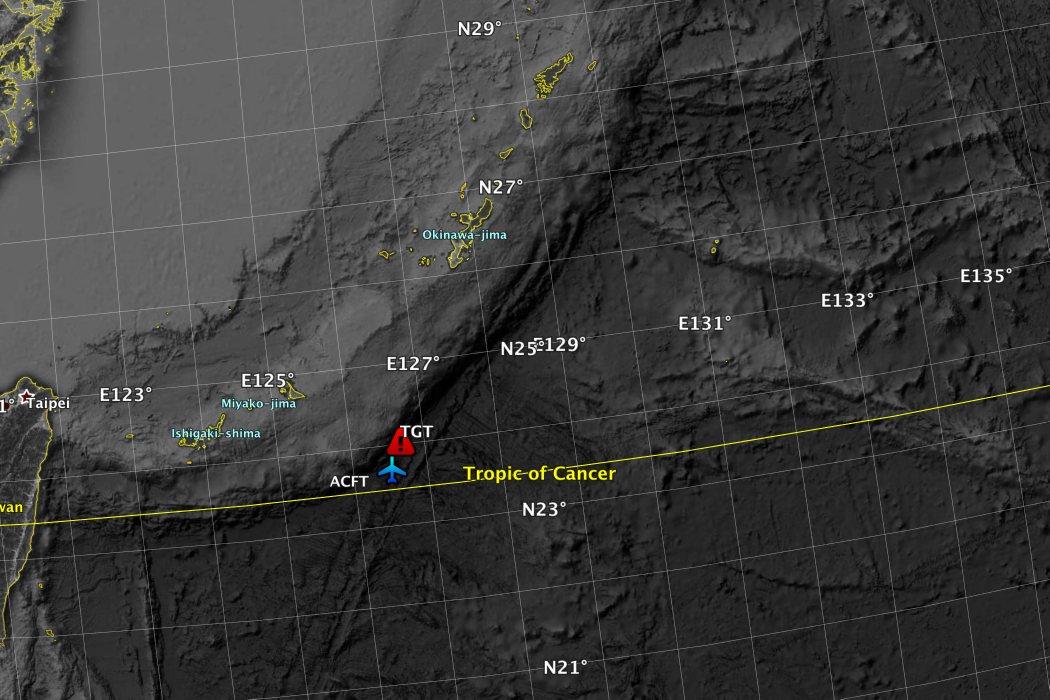

Scenario 2: Air Assault on Tiraspol

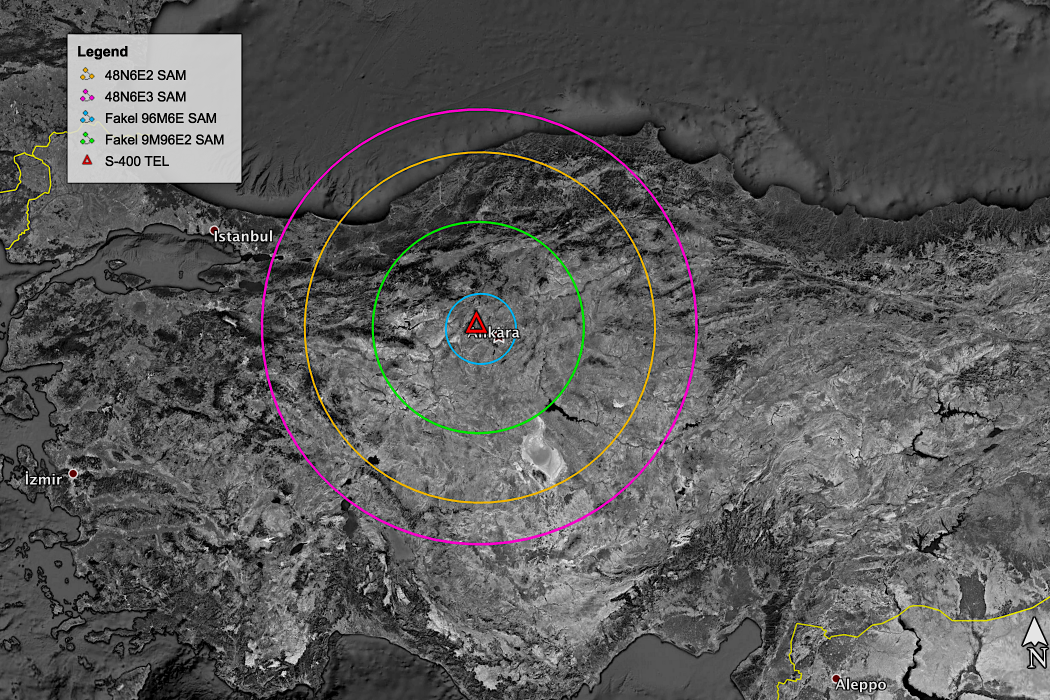

a. Pathway 1 (Direct Flight: Chernobayanka to Tiraspol, 230 km): Probably the most LOS route. VDV would launch from an airfield regularly hit by Ukrainian artillery, flying over a high-risk air defense area. There is likely a high density of Ukrainian-operated man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) with operators on high alert and increased readiness in the Mykolaiv-Odesa area. MANPADS of various ranges and kinematic effects provide a diverse and overlapping low-altitude, short-range coverage. Russian helicopters would need to fly low to minimize exposure to the Odesa-based S-300 radars, which would bring them right into the engagement envelope of MANPADS.

b. Pathway 2 (Avoid Odesa: Chernobayanka to Tiraspol, 340-360 km): This flight path significantly increases survivability by circumnavigating the large MANPADS concentration in the Odesa-Mykolaiv axis and S-300-controlled airspace. However, portable or mobile air defenses are likely also positioned west of Odesa, and increased flight time will limit the maximum take-off weight of the attack and transport helicopters. The longer the flight time, the higher the chances that NATO and Ukrainian sensors will detect the airborne assault from an early stage.

c. Pathway 3a (Direct flight: Crimean airfields to Tiraspol, 350-400 km): Another low survivable flight path. Flying through the S-300 “bubble” requires significant electronic warfare (EW) and anti-radiation support. The RuAF will likely need to conduct suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) sorties to open up the airspace for the VDV flight to Tiraspol. For example, the VDV’s assault on Hostomel airfield through Ukrainian air defenses was also enabled by a combination of electronic and missile attacks according to a RUSI report . However, the large density of MANPADS in Odesa poses a constant threat to low-altitude air operations., especially if the assault is not done under the cover of darkness.

d. Pathway 3b (Avoid Odesa: Crimean airfields to Tiraspol, 350-500 km): Probably the most survivable flight path but also the longest, which restricts airlift capacity (troop number and equipment quantity) and exposes the operation the most to NATO and Ukrainian radars and ISR assets (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance).

Note: The VDV is one of the most attrited Russian service branches in the war in Ukraine. Significant regeneration would be required before the VDV could hope to pull off such a stunt.

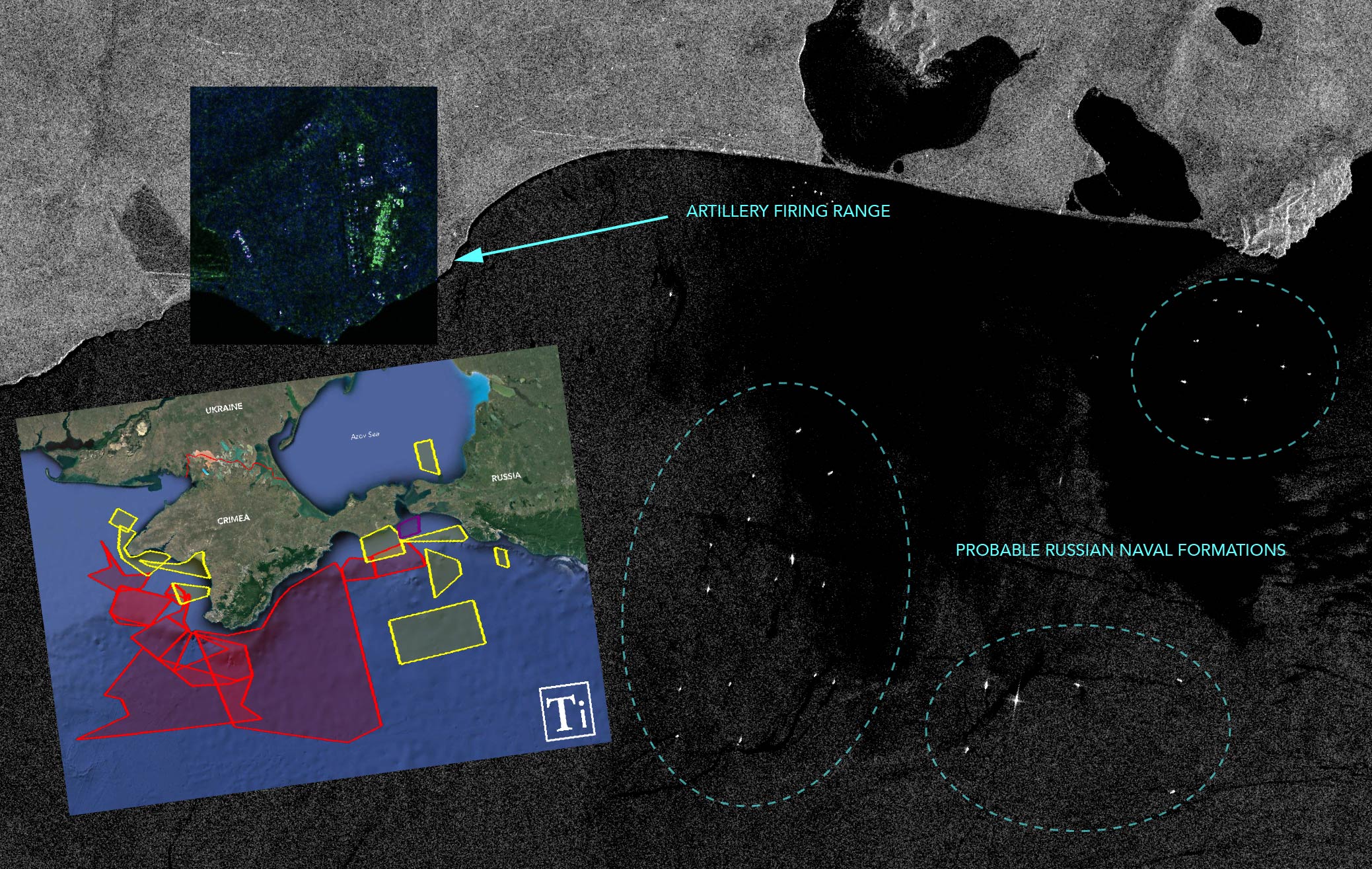

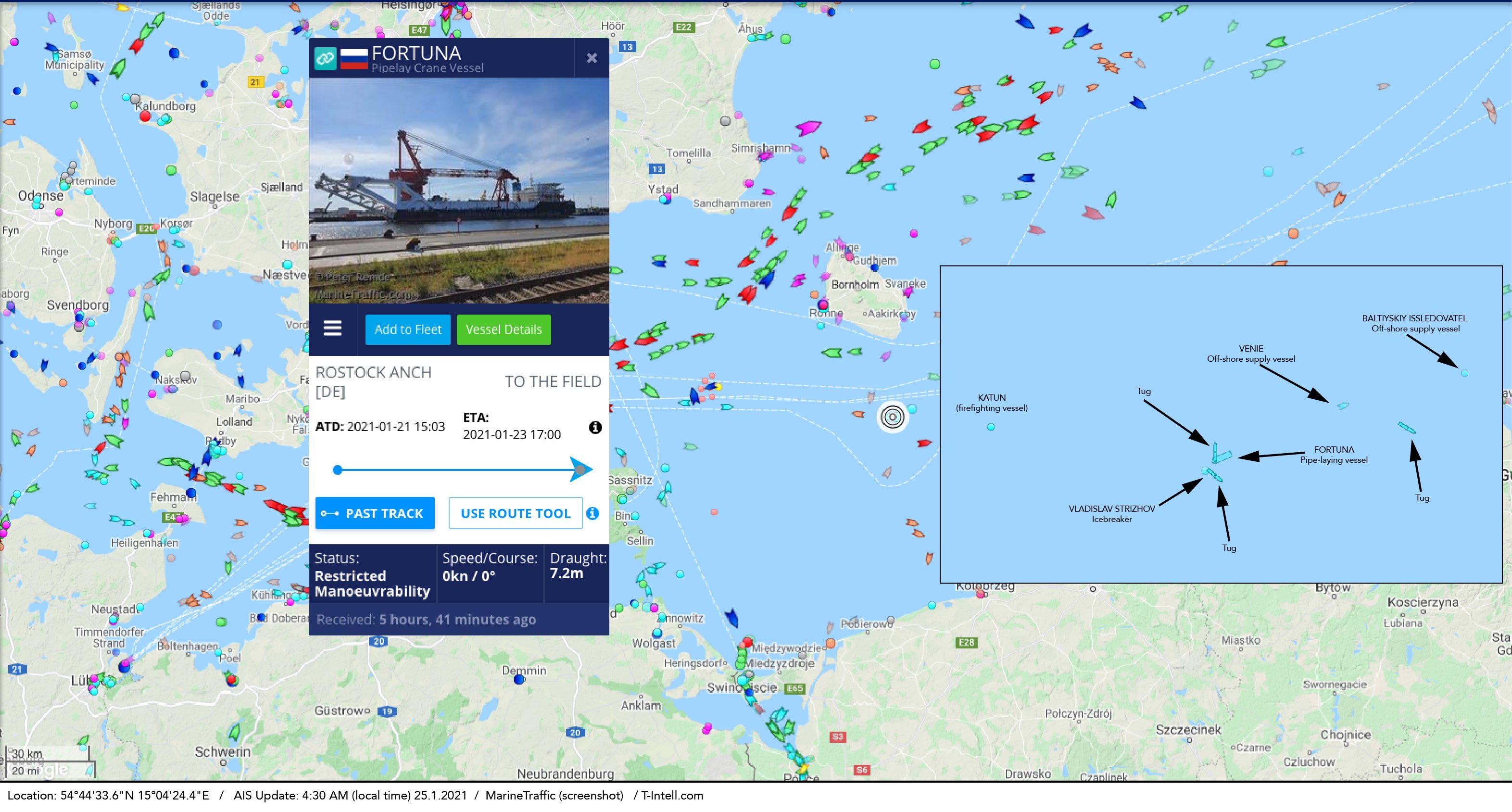

AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT ON BUDJAK

14. Following the forced closure of the Pidyomnyy bridge, many have speculated that Moscow may be eyeing an amphibious assault on Ukraine’s Budjak region (southern Bessarabia) – Ismail, Bolhrad, and Bilhorod-Dnistrovsky raions in western Odesa province. Russia’s supposed bet is that the landing would be unopposed as Budjak is undermanned by the Ukrainian military and largely disconnected from the rest of the country.

Scenario: Amphibious Landing in Budjak

15. An amphibious assault on Budjak is theoretically possible but technically difficult and of high risk. The Russian Navy would have to assemble an armada of amphibious vehicles, landing ships and craft, frigates, and other heavy warships, supported by air assets and likely surface to surface missiles. Preparations for such an operation would leave plenty of tell-tell signs that NATO could detect and forward to Ukraine.

16. Ukraine has mined Odesa’s littoral waters and lined up its shores with anti-ship missiles (AshM), including Neptune (300 km range) and, in the future, truck-mounted Brimstones (range unknown, likely short) – as promised by British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. The Ukrainian Navy has also effectively posed a credible anti-ship threat, using Neptunes to sink the “Moskva” Slava-class cruiser and Bayraktar drones to destroy patrol boats near Snakes Island.

17. Budjak’s shore is unideal for amphibious assaults. The coastline mainly consists of small and narrow beaches excavated below the street level with no connection to road networks. Most beaches are flat and lack cover or port facilities. The defender has a clear high-ground advantage. Other areas of the Budjak are dominated by lagoons where landing parties can easily become trapped. Negotiating the terrain is possible in some areas but would make for a sluggish escape from the “deathtraps” that are Budjak’s beaches.

18. Provided the landing is successful, the amphibious force would need to bolt towards Moldova’s Stefan Voda raion and link up with Transnistria. Russian troops would need to occupy Stefan Voida raion to ensure a land link to the OGRF and deny the last LOC from Romania’s southeast (NATO) to Ukraine. The OGRF could help by mimicking feint attacks from Bender (Tighina) towards Anenii Noi or Causeni and distract the Moldovan military.

19. The operations’ success rests on whether the landing party could secure the Budjak bridgehead and sustain an incursion towards Transnistria at the same time. A successful Ukrainian counter-attack could split the invaders into two vulnerable pockets to be captured or annihilated.

ENDNOTE

20. Since it further invaded Ukraine in late February, Russia has demonstrated a severe lack of risk aversion regarding military action. Moscow may continue to greenlight operations that are objectively “suicidal” or “likely to fail.” Russian military commanders might interpret the operational success probability differently and assess that the payoff would offset the costs. While these notional scenarios are purely an exercise in imagination, they could be options on the table for Russia.

by HARM

editing by Gekco

DISCLAIMER: This report is legacy content published before T-Intelligence’s relaunch on 4 July 2023. The report has been retained for archival purposes, but the content may not align with current standards.

Founder of T-Intelligence. OSINT analyst & instructor, with experience in defense intelligence (private sector), armed conflicts, and geopolitical flashpoints.

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 1]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/KLZJan.62018copy_optimized.png)

![Pride of Belarus: Baranovichi 61st Fighter Air Base [GEOINT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/cover_article.jpg)

![This is How Iran Bombed Saudi Arabia [PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/map4cover-01-compressor.png)

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 2]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TelSalman24.2.2018_optimized.png)