Strategic Analysis (20 min read) – The Syrian quagmire is nearing the end. The Assad regime is quasi-victorious with more than half of the national territory regained and over 75% of the Syrian population under its control. The Opposition forces are utterly degraded and boxed into a few isolated patches of land in the western parts of Syria. The Russian Armed Forces as the Iranian-backed Shi’a paramilitary groups have played a key role in this effort. The military intervention launched in 2015 was mostly motivated by long-term strategic goals that seek to undermine NATO’s southern flank and push forward the agenda of resurgence. Inherently, the Russian Federation will maintain a permanent military presence in the Mediterranean Sea and the Levant amid the end of the Syrian Civil War. The Latakia Air field will continue to host dozens of fighter jets and bombers, while the Naval Facility of Tartus will be enhanced to form a Mediterranean Fleet consisting of a nuclear submarine and 11 warships. Guarded by the S-400 system, the Russian military-assets on the Syrian coastline form a new Anti-Access Area Denial Zone (A2AD). The strategic ramifications of these actions are to vanguard the Bashar al-Assad regime in Damascus, challenge NATO’s freedom of maneuver on its southern flank and enhance Russia’s geopolitical posture and security needs throughout the region and the world.

(Electronic references are embedded in text via hyperlink)

Little Green Men in Syria: Context, Origins and Developments:

The Russia State Duma authorized in mid-2015 the deployment of troops in Syria. The Regime of Bashar al-Assad submitted an official request to Moscow for military support. Weakened by defections and casualties, the largely conscripted and weary Syrian Arab Army (SAA) was close to collapse. This would have been catastrophic to Russia’s long-term strategic plans and shorter-term goals.

The military intervention to support the Assad regime and decisively aid the Loyalist war effort was motivated by several factors:

Grand Strategy of Resurgence. Vladimir Putin continues to see the relationship with the West as a zero-sum game, that can be leveraged to assert the strategy of reviving the Soviet-era influence and posture. The West had little-to-no appetite for a new intervention in a Middle Eastern quagmire, however, Russia still tried to deny Syria for the U.S. or the Sunni-block (aligned with the West). In the process, the Kremlin sought to use Syria to establish an active operational presence in the Middle East. This required the construction or enhancement of military installations (ex: Latakia Air Field & Tartous Naval Facility), the deployment of significant troop numbers and advanced hardware (ex: S-400, Iskander). On one hand, the establishment of such a persistent active force also provided Moscow with the opportunity to battle-test its troops and showcase new technology; essentially using the Syrian theater of War as both a battleground and a showroom. On the other hand, it allowed Russia to transform its initial “expeditionary” posture into a permanent-strategic one. This resulted in the creation of a new Anti-Access Denial Area (A2/AD) and laid the foundation for a future Mediterranean Fleet, targeting NATO and the U.S. The confrontation with the West remains an influential mindset in contemporary Russian strategic culture and planning.

Russian soldiers doing target practice in the Mediterranean Sea from the Tartus port, Syria.

Domestic affairs. The internal context in 2015 was defined by the negative impact of the Western-sanctions imposed to Russia. The economy was taking hits in trade, inflation was on the rise subsequent with the devaluation of the Ruble. The few opposition parties began capitalizing on the huge costs of the illegal annexation of Crimea. Putin’s popular perception spikes in the opinion polls when he confronts the West. Inherently, Syria was yet another opportunity for exactly that.

Historical heritage. Since 1971 when Bashar’s father, Hafeez al-Assad seized power in the government and the Ba’ath Party through a coupe d’état, Syria immediately became an accommodating ally for Russia. In 1971, the Syrian Government leased the port of Tartus to the Russian Navy, developing a naval maintenance facility to support incursions in the Mediterranean Sea against NATO. The single-party system ran at Damascus took inspiration from the Soviet Union and sought to remain affiliated with the satellite system of the Eastern bloc, and its military aid. Together with Nasser’s Egypt, Syria was Moscow’s backbone in the Middle East. The contemporary Syrian-Russian alliance has its roots in the Soviet-era foreign policy.

Geo-economics. Syria has remained the top buyer of Russian/Soviet-made weapons and military technology. This amounts to a considerable fraction of Moscow’s revenue from a strategic economic sector: weapons trade.

Energy Security. The energy potential is significant for a top player on the market such as Russia. Leaving aside the fertile lands of eastern and central Syria, Damascus promised to outsource the exploitation of off-shore gas deposits to Russian companies. These enterprises have already enlarged their market share in the region due access to northern Iraqi oil & gas deposits, and could potentially link their assets into a robust energy network in the Middle East. This will allow Russia to further control production, transportation hubs and deepen its monopoly of supply to the European market.

National Security and Counter-terrorism. Attempting to draw thousands of extra-national Muslims into their ranks and aid their respective cause, several groups emphasized the Islamic component of the war and called for a mobilization of the Ummah. The main beneficiary were the Salafist groups affiliated with al-Qai’da: Jabhat al-Nusra (now Hayat Tahrir al-Sham/ HTS) and the splinter group, the Islamic State of Syria and Iraq (Da’esh/ ISIS). Spearheaded in Syrian and Iraq, the Global Jihad 2.0 promised by ISIS emerged as a major threat for the West and the entire world. This renewed menace promised deadly attacks overseas and mass-radicalization and recruitment of Western-born Muslims; and not only.

According to Vladimir Putin, 5,000-7,000 people from Russia and Central Asia are fighting on the side of ISIS. A study by the International Center for International Security found that half of those originated directly from Russia, while the rest were recruited through Russian jihadi networks. Another investigation, this time done by Reuters found that the Russian authorities softened the fight against domestic Islamic militants, allowing some to leave for Syria. According to the Syrian Opposition, Chechens are the second-largest ethnic group fighting Assad. It is assumed that thousands also joined the al-Qa’ida (AQ) affiliated groups in Syria as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) due to the historical ties it had with the self-proclaimed Caucasus Emirate. The previously mentioned group is the largest jihadi movement active in Chechnya and Dagestan. The front encompasses many factions that have later switched their allegiance to ISIS.

Beyond all doubt, Russia has a major terror problem. This will only amplify if the jihadist propaganda outreach is efficient, and when/ if battle-tested fighters return to their home country to plot attacks and enhance local insurgencies. In this regard, the military intervention of 2015 was largely branded as an anti-ISIS operation. However, studies as the ones conducted by the Institute for the Study of War have proven that “the Russian air campaign in Syria appears to be largely focused on supporting the Syrian regime and its fight against the Syrian opposition, rather than combatting ISIS.” This observation is also backed by a Reuters analysis showing that 80 percent of Russia’s declared targets in the first months of intervention in 2015 have been in areas not held by Da’esh. These studies are also enforced by own data analysis based on official and reported air strikes and their location. Undoubtedly, a significant portion of the Opposition is represented by AQ-affiliated jihadi groups of which termination is beneficial. However, this does not take from the fact that the campaign was miss-advertised and has systemically ignored ISIS (the recruiter of thousands of Russian citizens) until the 2017 Astana Accords that brokered a cease-fire with the Opposition groups. Nor does it excuse that Russian air strikes also targeted vetted and legitimate Opposition groups that disavowed or fought their radical peers.

Legitimate and factual as the counter-terrorism concern may be, it was merely used as a P.R. tool to falsely-advertise what it was a genuine geopolitical move directed against the West, and in facilitation of the Kremlin’s goal of regaining some of its lost influence.

“Listening-in”

The Kremlin’s asset-building started long before its formal combatant intervention in the Syrian Civil War in September 2015. The first conflict-related installations were Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) outposts:

(1) One, located on the coastline of Latakia, was considered to be the largest external intelligence collection facility that the Kremlin operated.

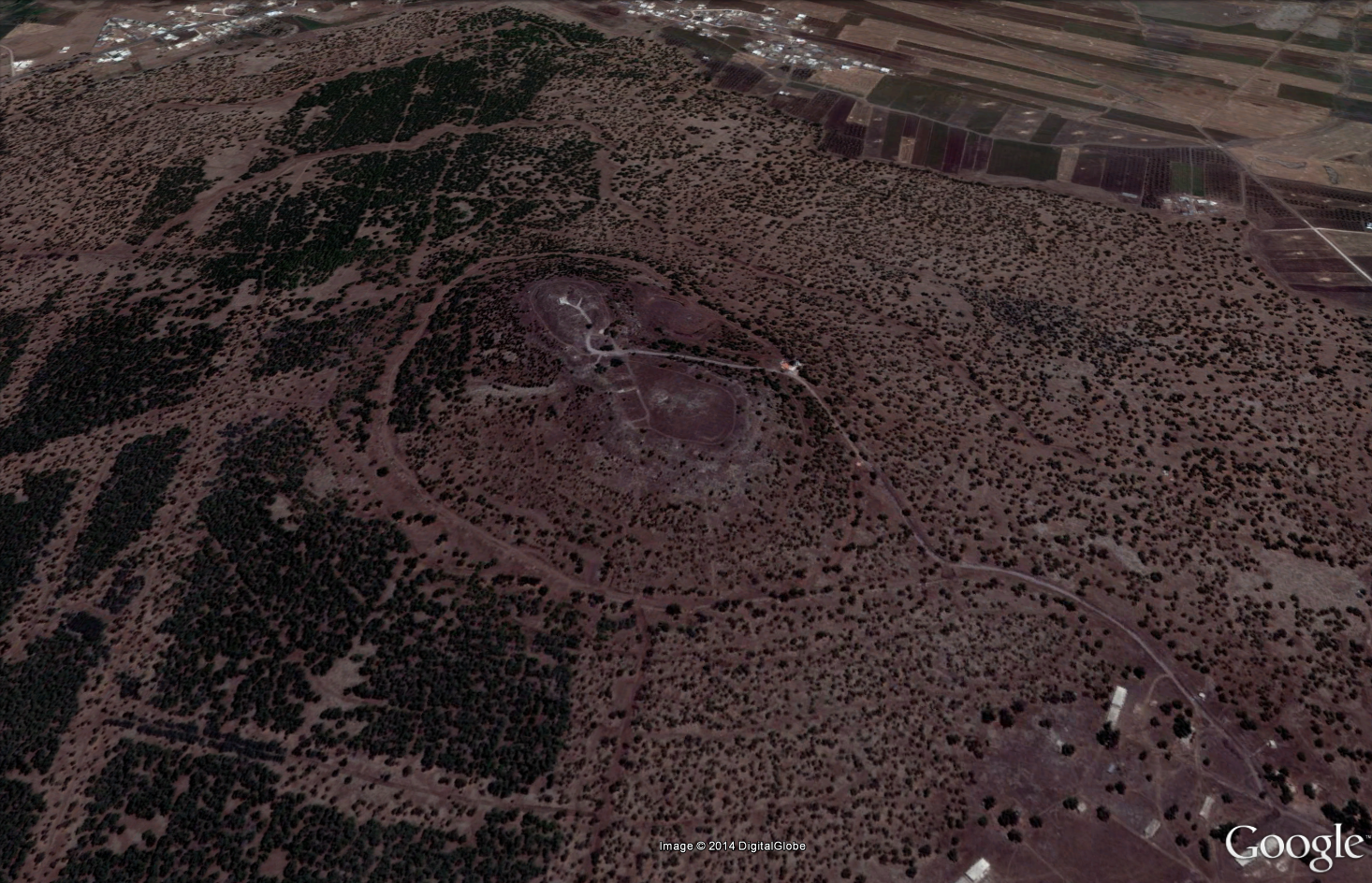

(2) Another base, presumed to be titled “Center S” was located in al-Hara, Da’ara governorate in Syria’s deep south. The facility was jointly operated between the radio-electronic unit of the Russian Foreign Military Intelligence (GRU) and their Syrian counter-parts. Their efforts were directed at recording and decrypting radio communications of the Syrian Opposition groups. The revolution began in Da’ara province, therefore key influencers and leaders were to be tracked and neutralized in that area. The Belingcat determines that this facility is at least partially responsible for high-value target (HVT) acquisition and neutralization of Opposition commanders, rendering it strategically important for the Assad regime. The Northern Military District of the Israeli Armed Forces based in the Golan Heights was also the target of communications interception. This suggests that the installation might have pre-dated the Syrian Civil War, and that the initial purpose was more related with the Israeli-Arab confrontation, than counter-insurgency efforts. This hunch is also backed by a disclosure made by the Debka File as appeared in the Washington Times. The private-Israeli intelligence firm revealed in 2012 that Russia expanded and upgraded the radars used at the surveillance station. The range was reportedly extended to all parts of Israel and Jordan and as far south as the northern Saudi Arabia. It was also reported that Iranian concerns of a regime change at Damascus was key in enhancing the outpost’s capabilities. Various photos pinned to walls show visits from top-ranking senior military officers of the Russian Armed Forces or from Kudelina L.K., Counselor to the Minister of Defence of Russia. (translation provided by Belingcat and Oryx Blog).

Satellite photo of ”Center S” found by the Oryx Blog.

The outpost was abandoned when Opposition groups stormed it in October 2014. Rebel commanders later issued videos and photos of the sensitive information found inside the facility. The raw data was exploited by the public sphere and open-source analysts to determine the scope and scale of this facility. The network of SIGINT stations used to spy on Israel and later, on the Opposition groups is believed to be wider and concentrated in Da’ara province.

Active Operational Presence (AOP):

Logistics and hardware are key in assuring functionality and efficiency in military operations. In order to accommodate the thousands of troops, dozens of mechanized assets and fightersjets, the Russian Armed Forces relied on self-built facilities (some known, some rumored) and shared-bases with the Syrian Arab Army (SAA). The Khmeimim Air Base (Latakia province) and 1971-established Tartus Naval Facility (Tartus province) demands the most of our attention. They were built and enhanced on the Syrian coastline, a region largely inhabited by the governmental-loyalist and dominant, the Allawites. This region is a stronghold for the Bashar al-Assad regime (an Allawite himself) due to the sectarian history that promoted Allawites into top military and political positions following the instatement of the Assad dynasty in 1971.

“Bunk buddies”

There are also known joint military installations with the Syrians and Iranian. These most likely serve as a temporary accommodation for the Russian Armed Forces, respective of their ongoing operations:

Tiyas (T4) Air Base (Tadmur/ Palmyra, Homs province) – largely used for the three battles of recapturing and defending Palmyra/Tadmur from ISIS.

Shayrat Air Base (Homs province) – The presumed air base used for launching the chemical strike against Rebels and civilians in Khan Shaikhoun (April 2017). The military base was hit by the U.S. with 59 tomahawk cruise missiles in retaliation, damaging hangars and fighter jets. This is the last remaining major air field operated by the Syrian forces.

Shayrat Airbase (photo source: iSi)

Deir ez-Zor Air Base (Deir ez-Zor province) – under siege between 2012-2017, it was exclusively supplied through an air bridge. Russian assets were only deployed there in late-2017 when the area was liberated. This base served in support of expeditionary operations on the mid-Euphrates valley and all the way to Abu Kamal.

Observation Post in the SDF-held Afrin canton (Aleppo province) – the Afrin canton is isolated from the rest of the Federation in Northern Syria. It is an enclave between Turkey and the Turkish-controlled northern Aleppo. It is administered by the U.S-backed and YPG-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The YPG brokered an uneasy deal with Russia to shelter it from Turkish attacks. Russian forces were deployed in the area in mid-2017 and established a small observation post to monitor the tensions. In December 2017, reports suggested that the Kremlin was pulling-out its troops, accommodating the Turkish plans of besieging and liberating the area, in exchange of handing Idlib province to Russia.

Khmeimim/Hmeimim Air Base, in Latakia

In mid-2015 Russia began establishing an air base in extension of the International Bassil al-Assad Airport in Latakia, on the Syrian coastline. Advertised as Russia’s strategic center for combating ISIS, the base was leased by Damascus free of charge and for an undefined limit of time as signed by a bilateral accord in August 2015. New amendments have been brought to the treaty in January 2017 that leases the Hmeimim aerodrome for 49 years to the Russian Armed Forces with subsequent extensions over 25-year periods. The same deal applies for the Tartus Naval Facility. The external perimeter of the base has Syrian military protection, while the inside is bound to Moscow’s jurisdiction, embedded personnel and their family receiving diplomatic immunity and privileges.

Russian military engineers repaired and extended the runaways to suit fighters jets, troop carriers and heavy transport cargo plans to land and take-off. RT was granted exclusive access to the Air Field in October 2015, when the facility was still under works. They showcased air-conditioned and white-painted living quarters that could host over 1,000 personnel, in addition to aircraft hangars, field kitchens and even saunas.

The circumstantial purpose of this Air Base is to serve as a nerve-center for Russia’s operations in Syria. Serving as a launching pad for the vitally-needed airstrikes supporting the Syrian government. When the air campaign started in mid-2015 in Syria, about a dozen Su-25 ground-attack jets were stationed at the Air Field according to Washington Post’s estimates. Throughout the years, the number of fighter jets has varied and remained largely unknown. However, own estimates based on satellite imagery obtained by independent Twitter analysts and Jane’s intelligence via Airbus Defence & Space, showcase an average number of 23-26 jets.

A line-up of aircrafts from July 15, 2017 show: 11 Su-24s, 3 Su-25s, 10 Su-27s or 35s, 4 Su-3 and 6 Su-34, amounting to a record-high of 33 jets on the ground at once. The surplus of aircrafts came after a Russian MiG-29K from the sole Russian aircraft carrier, Admiral Kuznetsov crashed in the Mediterranean on November 14, 2016 following a problem with one of the arrestor cables. The Kuznetsov does not have a catapult to launch its aircraft and it relies on a ramped deck to get the jets aloft. Although the problems were known for the outdated Cold War-era ship, its deployment in the Eastern Mediterranean was more of a (failed) show of force attempting to replicate a modern U.S. Naval Task Force. Following the incident, the aircraft carrier was returned to the naval base in Sevastopol, Crimea, while the nine fighter jets (8 Su-33s and one Mig-29k) have been transferred to the Latakia Air Field – as revealed by Jane’s Intelligence satellite imagery analysis. This upped the number of fighter jets for a period of time, boosting the intense air campaign that besieged Aleppo until December 2016.

Afterwards, Vladimir Putin announced a partial withdraw of its aircraft and troops in early 2017. However, the number hardly decreased. Satellite images from May 2017 still showed around 26 fighter jets stationed on Latakia’s runway. And even though the Kremlin announced a third withdrawal of forces from Latakia, satellite imagery posted by Qalaat Mudiq Twitter shows a remaining air fleet of 17 jets. Other air assets such as helicopters (attack or transport) or surveillance planes have not been included in this analysis, although they have been spotted in large numbers on the Latakian runaways.

The following slideshow contains most of the visual proof supplied through satellite imagery, supporting the analysis of the aerodrome:

A2/AD– Closing the Southern Airspace?

In order to safeguard such a robust deployment, Russia made efforts to build an enhanced anti-air posture.

In the Mediterranean, the Kremlin followed the same recipe of creating A2/AD “bubbles” as in Kaliningrad, northern Kola peninsula and Crimea. Through its key military deployments, Russia established a combination of integrated strategically-important anti-air defense systems and tactical nuclear-capable offensive missile batteries, covered by Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) counter-measures. In Syria, such a robust posture is mostly hosted by the Air Field in Latakia. The purpose of an Area-Denial Access Zone (A2AD) is to deny NATO air superiority or presence in selected areas. This is also one of the most constant practices in Russia’s resurgence strategy. Anti-access capabilities are used to prevent or constrain the deployment of opposing forces into a theatre of operations, whereas area denial capabilities are used to reduce their freedom of maneuver once in a theater (Luis Simon; 2017). Russia attempts to prevent its opponents from establishing air supremacy in strategically significant regions.

Most probably, the Russian always had in plan to protect their vast military build-up by deploying advanced air-defence systems in Syria. But following the downing of a Mig-29 by a Turkish F-16 in November 2015, Moscow accelerated the deployment of the advanced S-400 surface-to-air missile system at the Khmeimim Air Base. The S-300 was also commissioned to guard the Naval Facility in Tartous, alongside a network of vessels equipped with mobile anti-air and anti-missile interceptors. The naval assets continue to patrol the Eastern Mediterranean and Syria’s shores.

On September 2017, Jane’s Intelligence reported the deployment of a second S-400 system in Syria. The claim was confirmed by satellite imagery provided by Airbus Defense & Space. The anti-air hardware was placed near Maysaf, a small city located in north-western Homs province. The move further enhances Russia’s overall anti-air denial zone doubling-down on the strategically important shore but also widening its reach over the central Syrian airbases in Shayrat and Tyras (Homs province). Combined with defensive hardware, Russia also deployed its utmost offensive arsenal.

In December 2016, the private satellite imagery company ISI confirmed the presence of two Iskander batteries at the Khmeimim Air Base. Additional photos acquired and analyzed by ISIS on January 2017 confirm the reports that Russia used the batteries to strike ISIS positions in Deir ez-Zor all the way from Latakia. This was most probably a show of force after their attempts to camouflage the ballistic system were unfolded by private satellites and was showcased all over the news. The presence of the Iskander in Syria was rumored since early 2016.

The Iskander-M is a tactical (short-range) ballistic missile system. According to CSIS’s Missile Defence Project the Iskander-M (extended-range) has a 400-500 km striking range. Due to its operational mobility, launch weight and payload, the weapon system can strike both stationary and moving targets, including SAM sites and hardened defense installations. It was purposely built to overwhelm enemy anti-air missile defenses in a flexible and timely manner. Most importantly, the Iskander-M is also capable of firing nuclear warheads. This is one of the strongest and accurate weapons in Russia’s anti-access strategy.

Further image analysis show that the Iskanders have their own launch pad in Latakia Air Base. Suggesting that the hardware is also in Moscow’s plan for the 49-year long presence there. Both the Iskander strike ranger and the S-400 cover zone encompasses the NATO strategic Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey, the British bases in Cyprus, Israel, Jordan and parts of Saudi Arabia. Without a doubt, the Russians created a AD/2D bubble in NATO’s southern flank.

A Mediterranean Fleet

Russia seeks to further contest NATO’s control of the southern flank by introducing a permanent Mediterranean fleet that would extend its military might in the Middle East and further enforce the A2/AD established in the area. These plans would add an element of strategic nuclear deterrence, and will seek to influence the geopolitical order in the Mediterranean basin. The long-forgotten port of Tartus plays the key role in this endeavor.

Since its foundation in 1971, Tartus was never considered to be a real military base. Officially registered as a Material-Technical Support Point (MTSP), the port was solely used as a local repair shop for Russian warships, sparing them from a trip way back to Sevastopol, Crimea in case of malfunctions.

Model of Tartus Naval Facility

Starting with the Syrian Civil War, this was used as a cargo hub for weapons transfers to the Loyalist camp. It later supported Russia’s war efforts against Opposition groups and ISIS. The port helped re-establish the 1992-dissolved Rusian 5th Operational Squadron that was purposed to counter the U.S. Sixth Fleet in the Cold War, and extend Russia’s sea power into the Mediterranean.

But as the conflict nears its closing fights, Moscow and Damascus signed a treaty extending the lease of the port for an additional 49-years. According to the TASS news agency, the deal, signed in early 2017 will expand the Tartus naval facility, Russia’s only naval foothold in the Mediterranean, and grant Russian warships access to Syrian waters and ports. Sergei Shoigu, the Russian Defence Minister stated that the structures built in Latakia and Tartus have begun forming a permanent presence in the region. The later will host a naval strike group consisting of a nuclear submarine and 11 warships. Everything except an aircraft carrier can be docked there. This will attract additional coastal missile defence deployments and anti-submarine measures. The Tartus build-up represent the bedrock of an upcoming Mediterranean Fleet armed with a strategic nuclear deterrent – escalating Russia’s posture from the tactical-limited Iskander.

Part of the strategy of recovering its lost power, Russia seeks to project trust into regional stakeholders. It hopes that as the West grows weary of further interventions, destabilized states as Libya and Egypt will seek Moscow’s help for combating terrorism. This will open the door for further weapons trade, military deployments (extension of power projection) and energy opportunities. However, Russia lacks both the intent and the capacity to do a better job at counter-terrorism than the West. As Chatam House notes, The real driving forces behind Russian involvement in the region are a mixture of ambition, opportunism and anti-Western sentiment.

In early 2017, Russia was believed to have deployed Special Operations Forces in an Egyptian army base near the Libyan border. US and diplomatic officials said that any such Russian involvement might be part of an attempt to support the Libyan military commander, Khalifa Haftar, who suffered a setback on oil ports controlled by his forces.

Overview of the Tartus Naval Facility

In Cairo, the Egyptian and Russian ministers signed a $21 billion deal to start work on Egypt’s Dabaa nuclear power plant. While just in November 2017, Egypt has reached a preliminary agreement to allow Russian military jets to use its airspace and bases. Egypt is the second largest recipient of U.S. aid from the Middle East, a country firmly aligned with the Sunni-block, and holds the naval access point for European energy and maritime trade.

Black Swans: Seafaring unpredictable waters

In such long-term and comprehensive strategic planning, unpredictability is a key input. In this case, the unknown knows are plenty enough. Russia vision for the Eastern Mediterranean is primarily marked be three main (but not limited to) wildcards:

- Long-term efficiency of the AD/2D;

- The geopolitical context of the region;

- Capability to secure its assets in Syria.

To echo Admiral Richardson the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, what Russia is doing is more of a wishful projection than actual “denying” adversaries. If the AD/2D bubble did control the Syrian airspace, then the United States would have been deterred from launching 59 tomahawk cruise missiles from the Eastern Mediterranean into a joint Syrian-Russian air base in Shayrat. It is true that Russian Command was notified beforehand in order to avoid unwanted escalation. The U.S. Navy was only targeting the Syrian Regime for its use of chemical weapons (CW) in Khan Sheykoun. But it is also true that Moscow could have operated its anti-air defense system (if it didn’t at that time) and (attempt to) intercept the ordinance – at least to send a message, if not to protect the air field. The notification came through the Qatar-based de-confliction line. That channel is used by US CENTCOM and the Russian Aerospace Command to conduct joint air control and avoid unwanted incidents. While rational from both parts to maintain a dialogue in such a crowded airspace, it is possible that Moscow would have imposed a complete no-fly zone if it had the power or the leverage to do so. Notably when competing in close operations room as the Raqqa province or the mid-Euphrates valley in Deir ez-Zor. Russia’s resurgence is real, the AD/2D is palpable and threatening, but it still cannot top Western technology and strategic planning.

On the long-run, the creation of AD/2D bubbles is counter-productive for the Kremlin. Moving advanced air defense and tactical nukes on NATO’s borders will only urge its richer and more capable Western adversaries to further proliferate precision-strike missile systems. A tech-race that Moscow cannot keep-up with, chiefly given its worsening economy. The United States will maintain its naval supremacy for the next decades despite any attempt from foes to compete.

In the current geopolitical environment, Russia’s plans are caught between a rock and a hard place. The Kremlin is playing Russian roulette in the Israeli-Iranian divergence. It simultaneously attempts to maintain its military cooperation with the Lebanese Hezbollah, Palestinian militias, Iraqi PMUs and Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps, and to pivot with Jerusalem. A gamble that has proven dangerous and inefficient. Russia failed to enforce its guarantees made to the Israelis, that Iranian-backed elements would not take positions near the Golan Heights or build military bases in southern Syria. In fact, the situation is worsening as Hezbollah and Iraqi PMUs have seized the Damascus-Baghdad highway, establishing a direct supply line between Lebanon, Syria and Iran. We can expect an increase in the number of IAF clandestine air raids tasked to neutralize Hezbollah HVTs and weapons transfers. This will render the Russian multilateral diplomatic engagement as a missed opportunity in a changing Middle Eastern order.

Recent Rebel attacks on the Latakia Air Base only shows that Russia and the Regime are still unable of fully securing vital and strategic assets from unsophisticated acts of aggression. Further, troop movements and hardware deployment have been poorly camouflaged by traditional or electronic means. In contrast, U.S. Special Operations Force in Syria enjoy far better operations security/ operational secrecy (OPSEC) than Russia’s. And this given the fact that the Western press is larger, more resourceful and freer to conduct such investigations.

End Notes

While a new tide is announced in the Eastern Mediterranean, the West is still able to operate in Russia-made A2/ADs. There is little to nothing that the Kremlin can do to compete with U.S. military superiority. However, given the sensitive emerging context in the Middle East, the build-up in Syria holds great potential for regional ambitions. This will provide the Russians with more opportunities to challenge NATO’s southern flank. Moscow’s new permanent fleet escalates tensions with the West, and raises key questions in regards to the freedom of navigation/trade and maritime security in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Non-hyperlink embedded References:

Charles K. Bartles (2017) Russian Threat Perception and the Ballistic Missile Defense System, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 30:2, 152-169

Luis Simón (2017) Preparing NATO for the Future – Operating in an Increasingly Contested Environment, The International Spectator, 52:3, 121-135

Founder of T-Intelligence. OSINT analyst & instructor, with experience in defense intelligence (private sector), armed conflicts, and geopolitical flashpoints.