KEY JUDGEMENTS

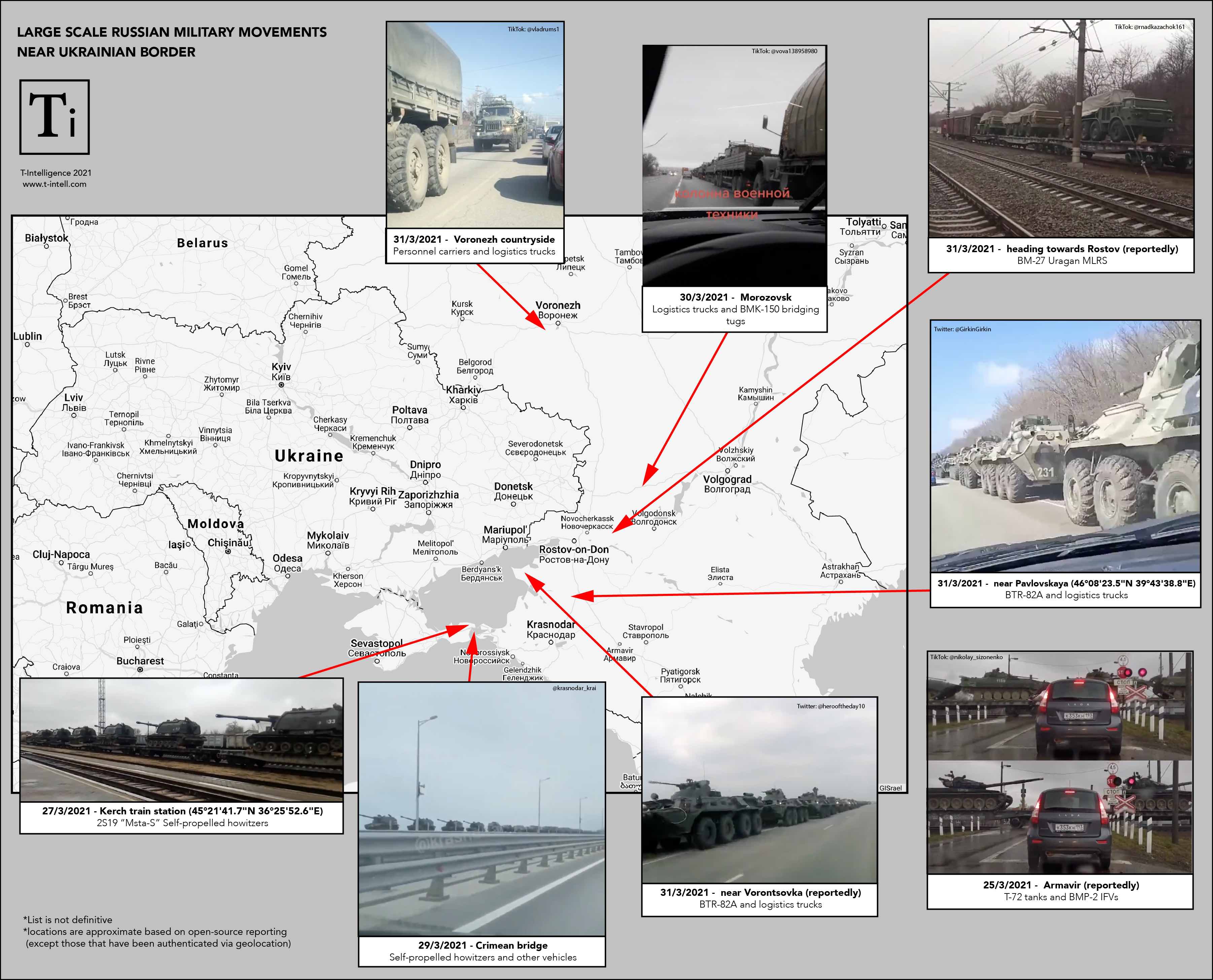

I. The Russian military build-up around Ukraine is designed for combat operations and not a show of force (“bear scare”). Our estimates are based on the unprecedented scale of Russia’s military build-up, the force composition in terms of capabilities, credible logistics, and increased operations security.

II. President Putin’s intentions remain unclear, but a military operation against Ukraine is moderately likely. The hypothetical campaign will likely be punitive, target Kyiv or Kharkiv, and seek to install or facilitate the emergence of a Russian-friendly “salvation” government.

III. Moscow’s diplomatic campaign around the build-up serves the informational offensive against NATO. Russia does not seek a political settlement to the current tensions and is well aware that its maximalist demands are non-starters for the West. However, these political talking points serve to shift the blame for the current tensions on the so-called “NATO expansion.”

IV. Only the threat of massive economic sanctions can alter Russia’s war plans. Ironically, NATO’s most unreliable member, Germany, holds the biggest financial leverage against Russia. Ukraine’s growing stockpile of ATGMs will be critical to slow down an armored assault and impose costs on an aggressor but have no strategic value.

READY FOR COMBAT

UNPRECEDENTED BUILD-UP

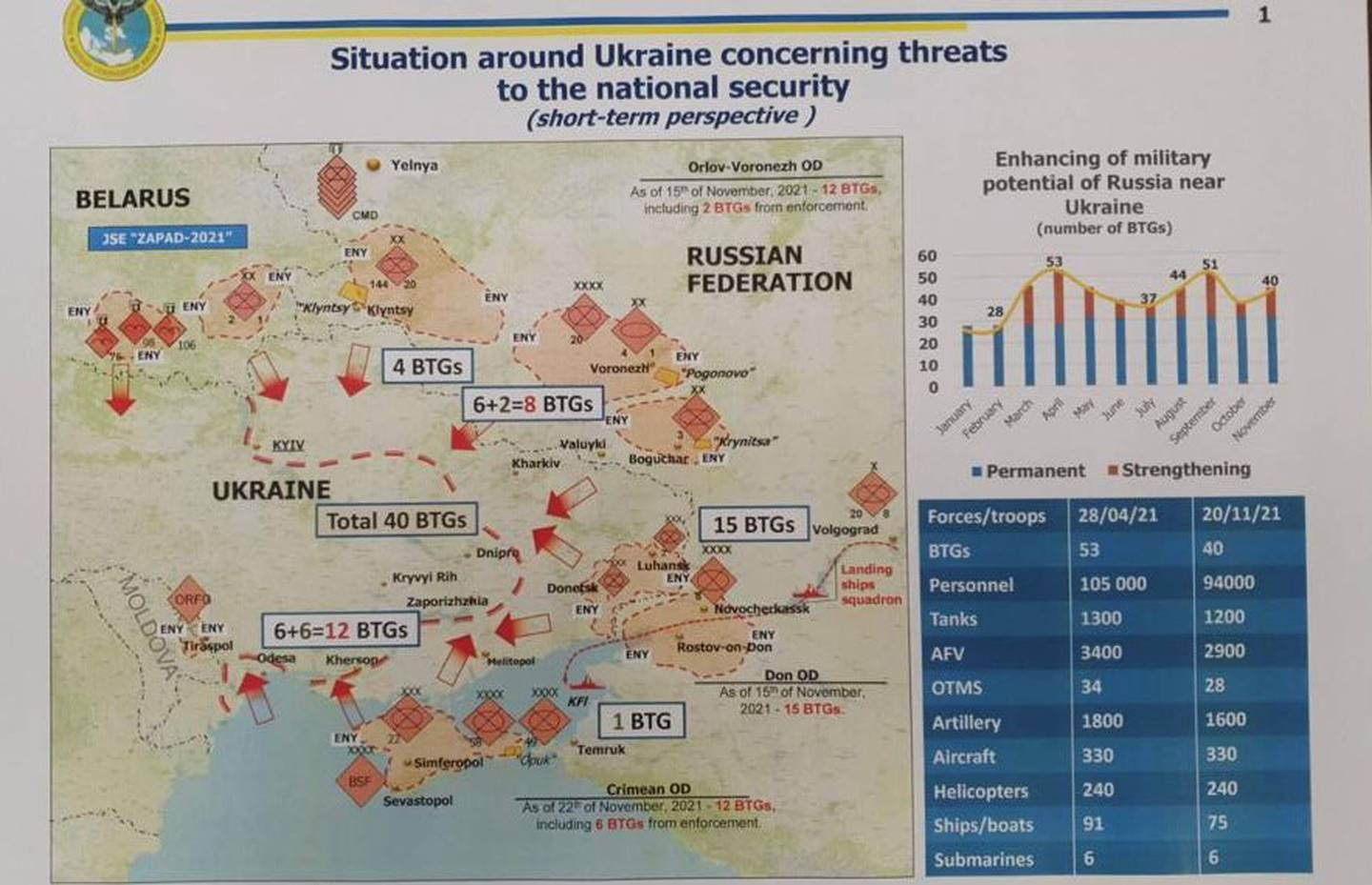

1. Russia has amassed around 100,000 troops, organized in 50 to 60 Battalion Tactical Groups (BTGs*), in five areas bordering Ukraine. The mobilized force represents roughly 30% of Russia’s 168 BTGs. This is the largest Russian build-up in modern history, far exceeding the number of BTGs deployed to annex Crimea (approx. four) and subsequent offensives in Donbas (five to eight).

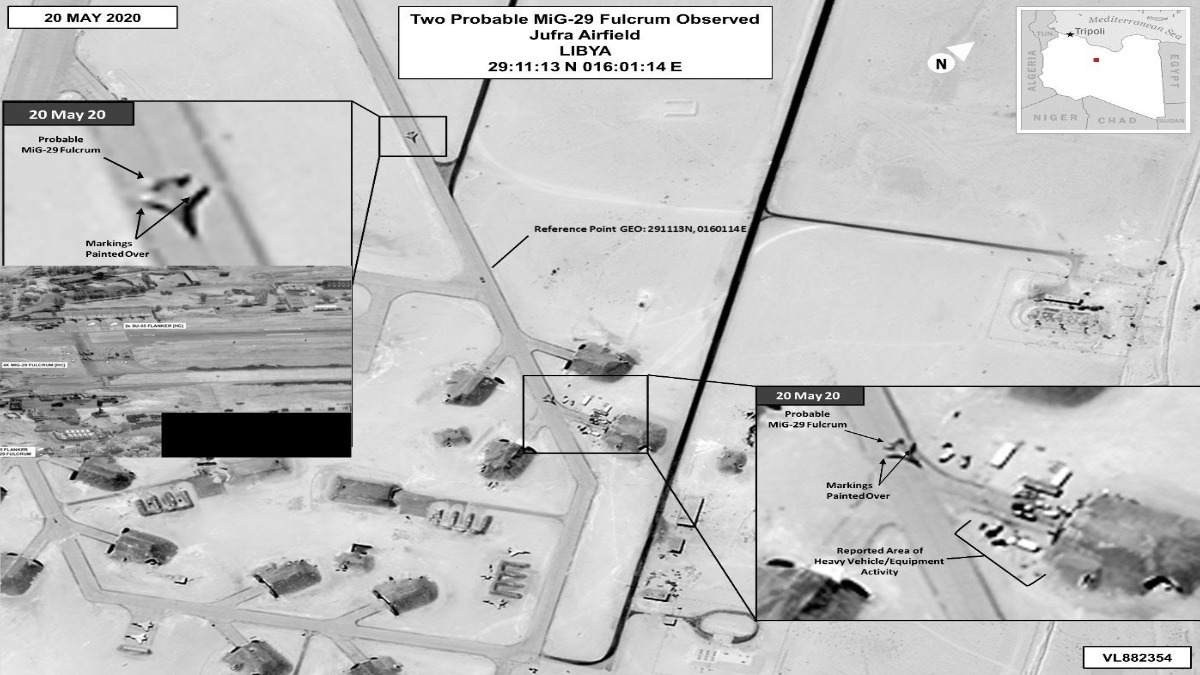

A substantial part of the BTGs deployed around Ukraine consist of equipment without personnel. However, Russian General Staff can deploy forces to man the equipment at a moment’s notice, especially using airlift capabilities (as recently demonstrated in Kazakhstan). In addition, a large portion of the troops has been permanently based near the Ukrainian border since 2021 or earlier.

*BTGs are temporary operational formations of infantry battalions and attached artillery, air defense, engineering, and logistics support units for combat operations, as part of motor rifle and tank brigades. Air assault units, special operations forces, and other echelons can also be attached to a BTG.

*Estimates on BTG posture: Ukrainian military intelligence estimates of 40 BTGs from late-November 2021 serve as a baseline layer (now dated and exceeded), followed by personal approximations in January, and most importantly, taking into account more precise calculations from Rochan Consulting (54 on 17 January 2022) and Michael Kofman, director of Russia Studies at CNA (55-60 on 15 January 2022).

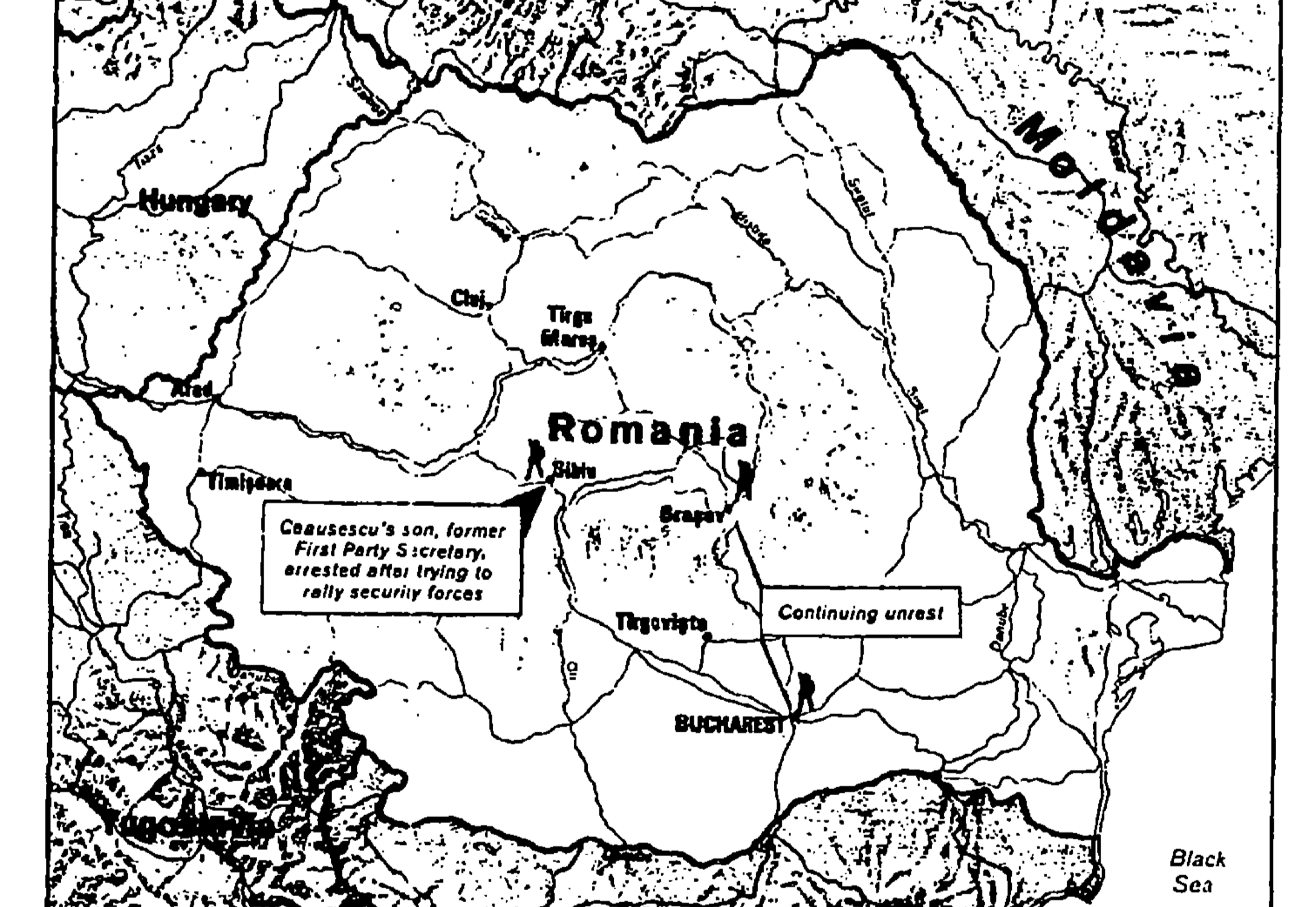

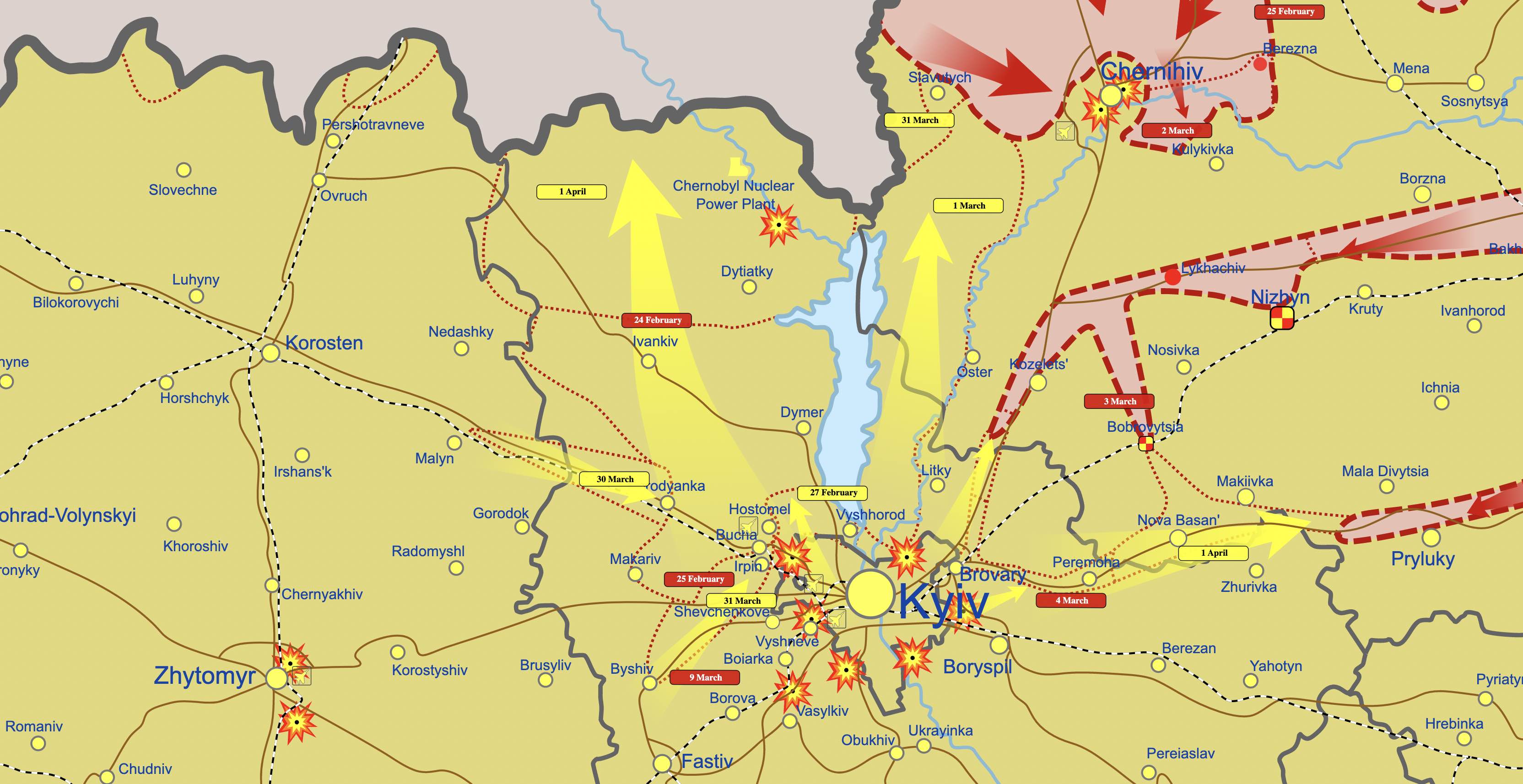

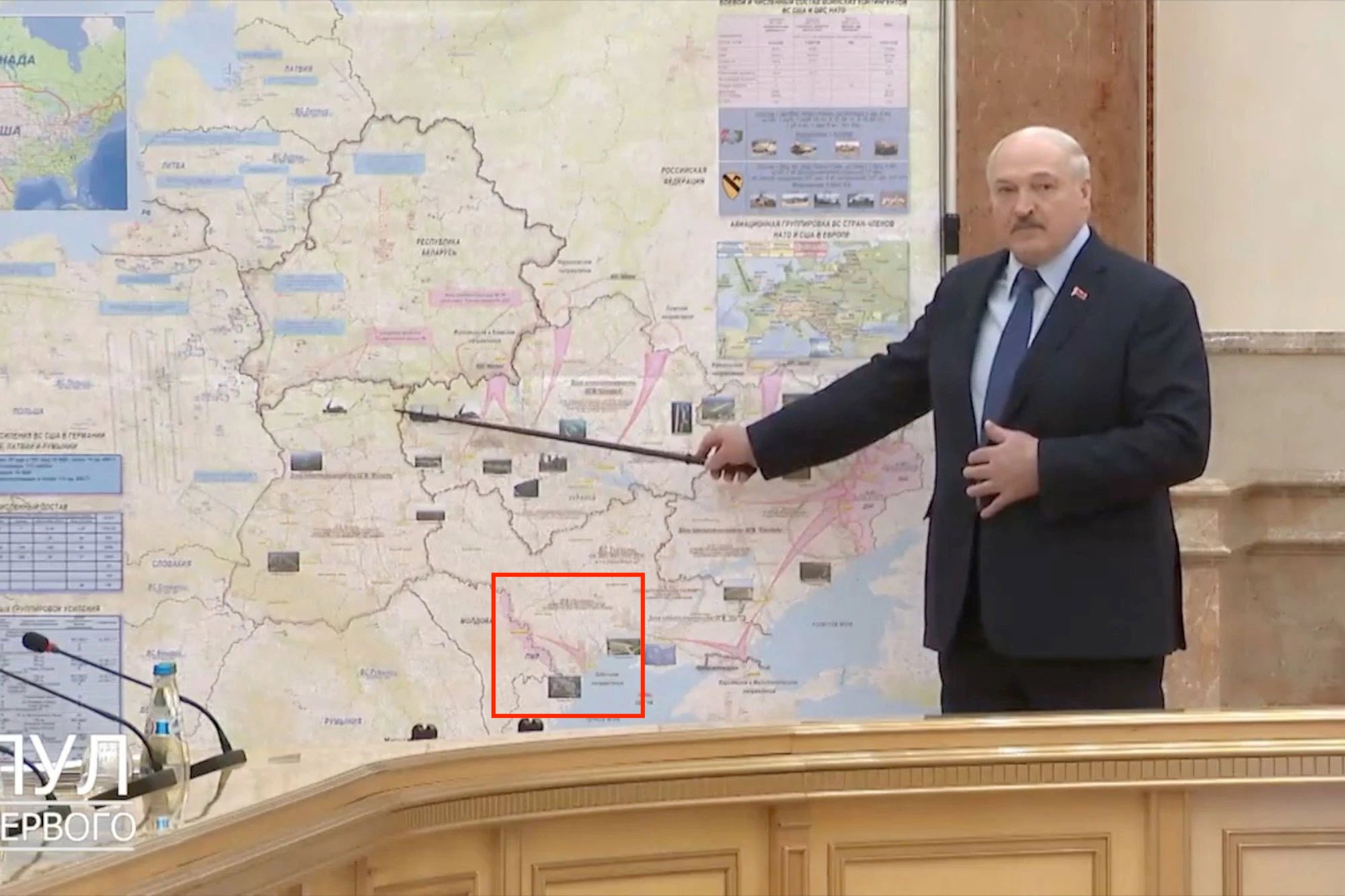

Overview of Russian military build around Ukraine. Note that the map is slightly outdated and does not show the units recently amassed in southern Belarus. (source: New York Times)

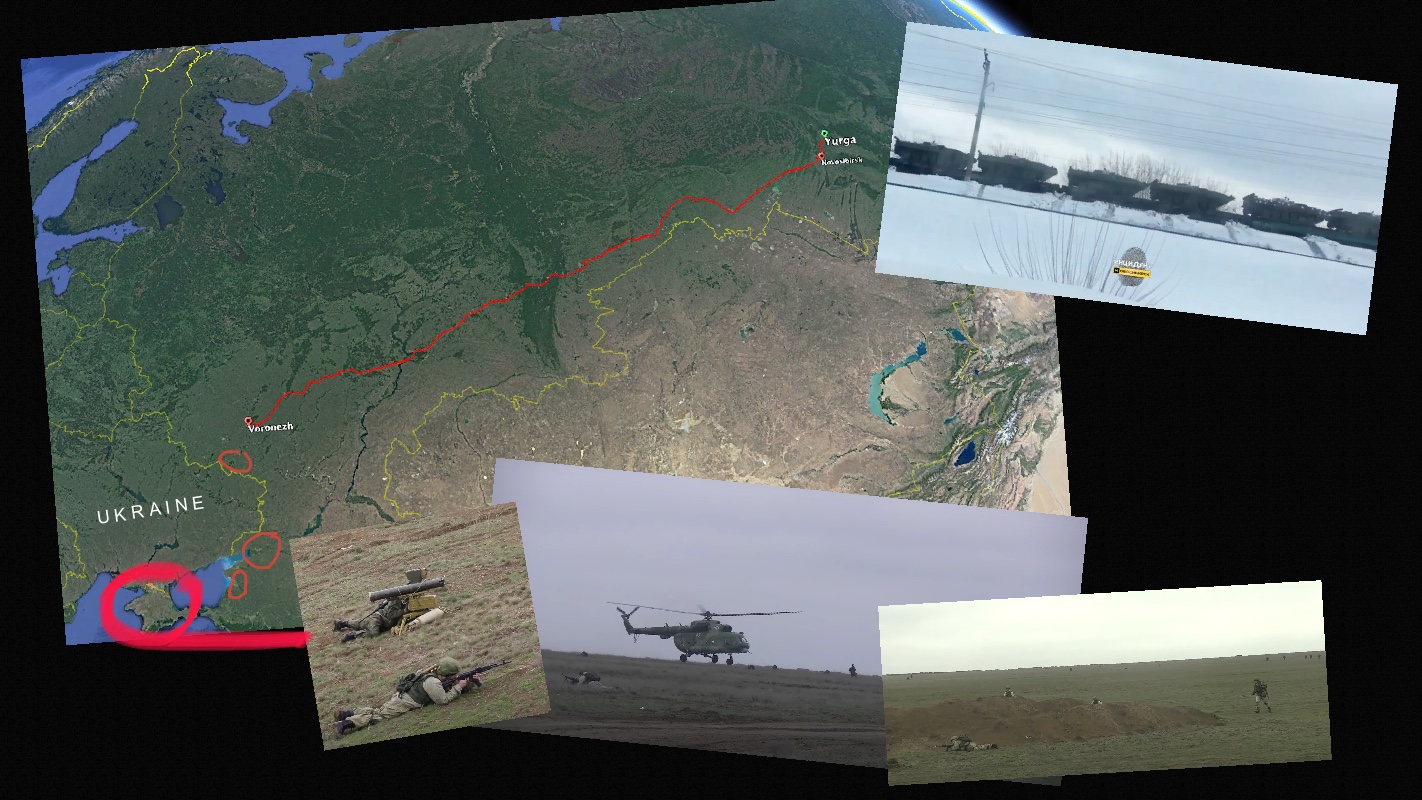

2. Four out of five Russian military districts have provided units for the build-up, including four field armies from the Eastern Military District (EMD), which are heading towards Belarus for the first time. The level and scope of cross-theater deployments are out of the ordinary and represent a significant logistical strain on the Russian military.

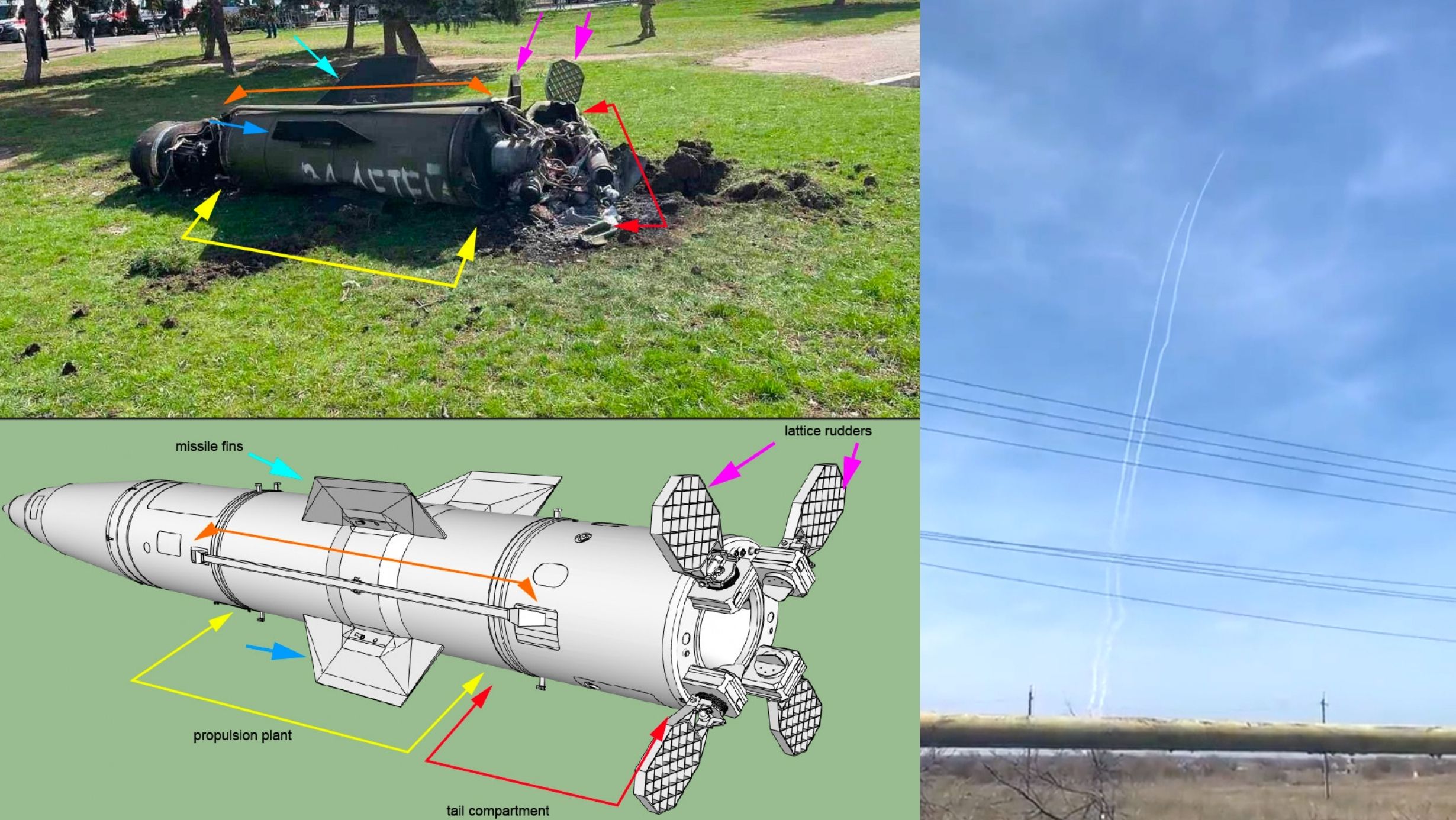

3. Russia’s build-up continues to escalate in scope and complexity. Ongoing troop movements to reinforce established positions, deployments of advanced weapons capabilities like Iskander short-range ballistic missiles (SRBM), and opening a new front in southern Belarus underscores the continuity of the operation. US intelligence estimates that the Russian build-up will ultimately amount to 175,000 troops/100 BTGs.

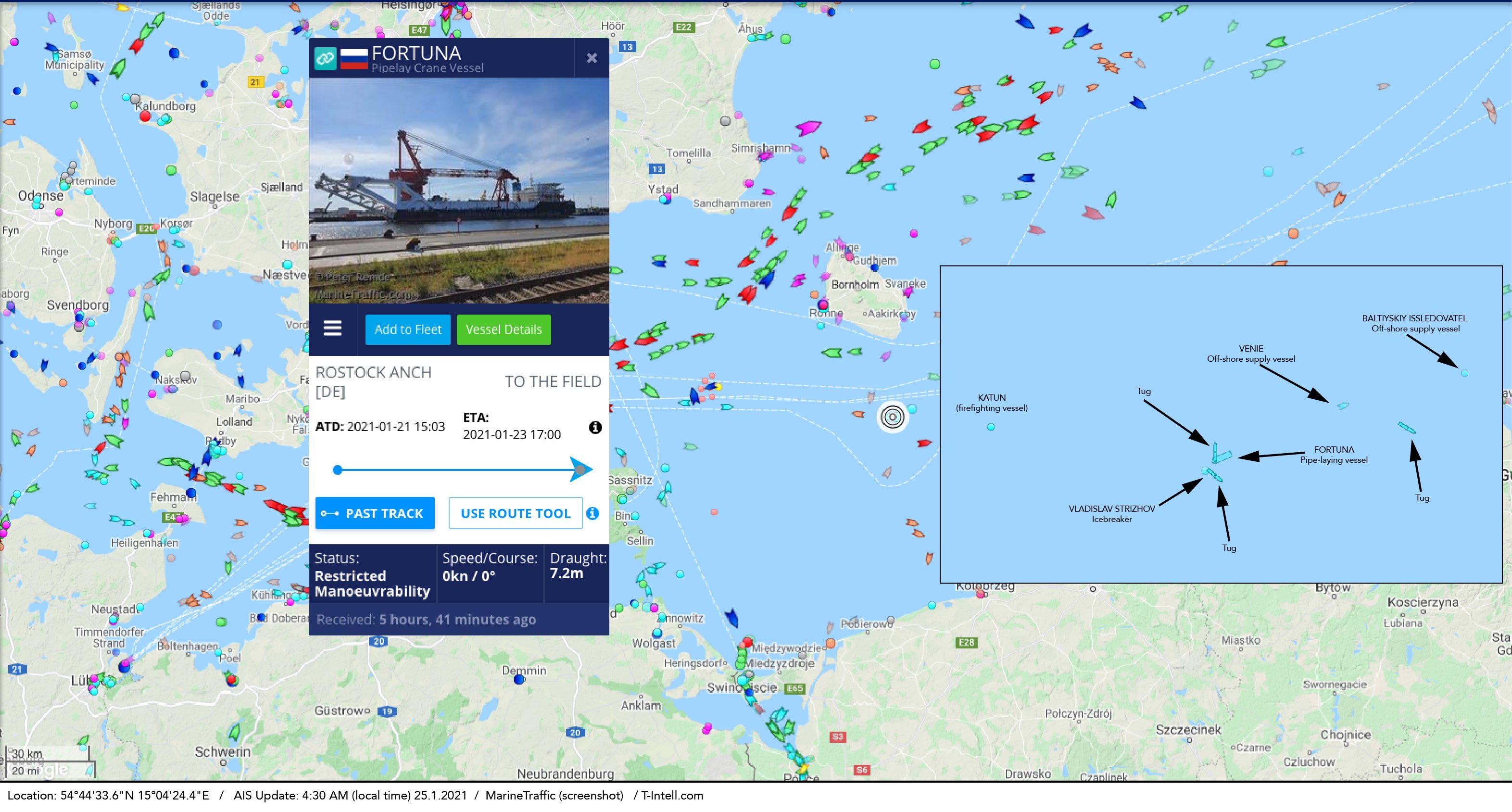

LOGISTICAL PREPARATIONS

4. The flow of logistical units and equipment to Ukraine’s border is the clearest indicator of a build-up with the intention of combat, apart from the unprecedented manpower involved. Eyewitness footage on social media has documented the westward movement of Russian fuel tankers, bridging/pontoon equipment, recovery trucks, transloaders, and other utility vehicles on railcars from late October to mid-December 2021.

5. Logistical movements have re-intensified between January 15-20, 2022, despite a slowdown in the previous month. Railcars now mostly service routes from Siberia, delivering EMD hardware and personnel, to southern Belarus. These transports can be subject to delays caused by bad weather, mechanical issues, or other obstacles that arise on long-term deployments.

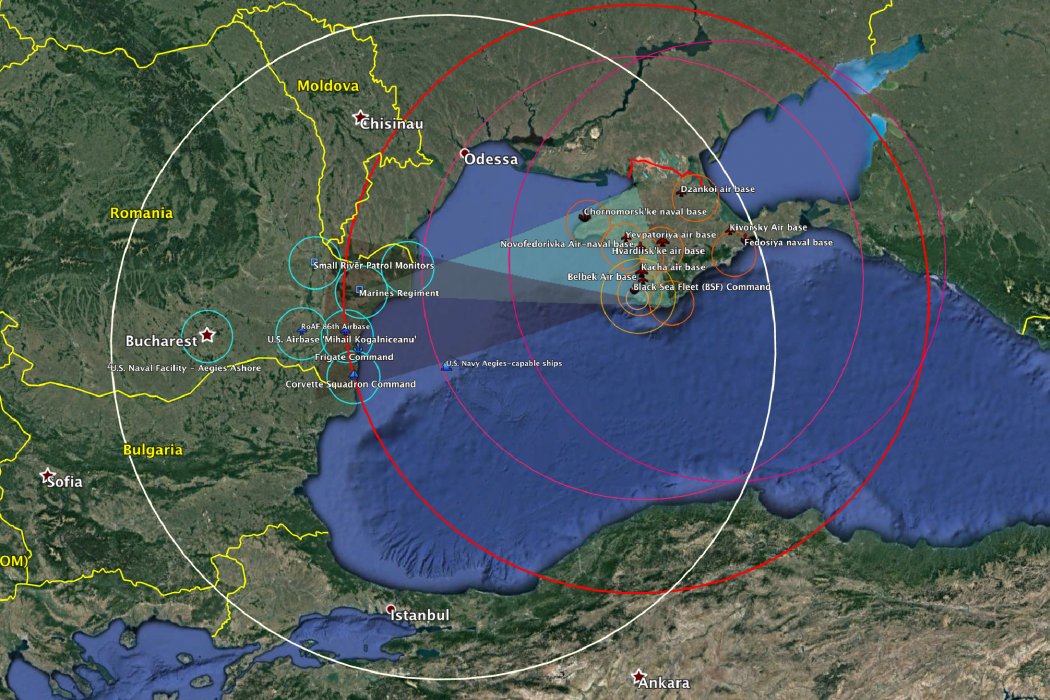

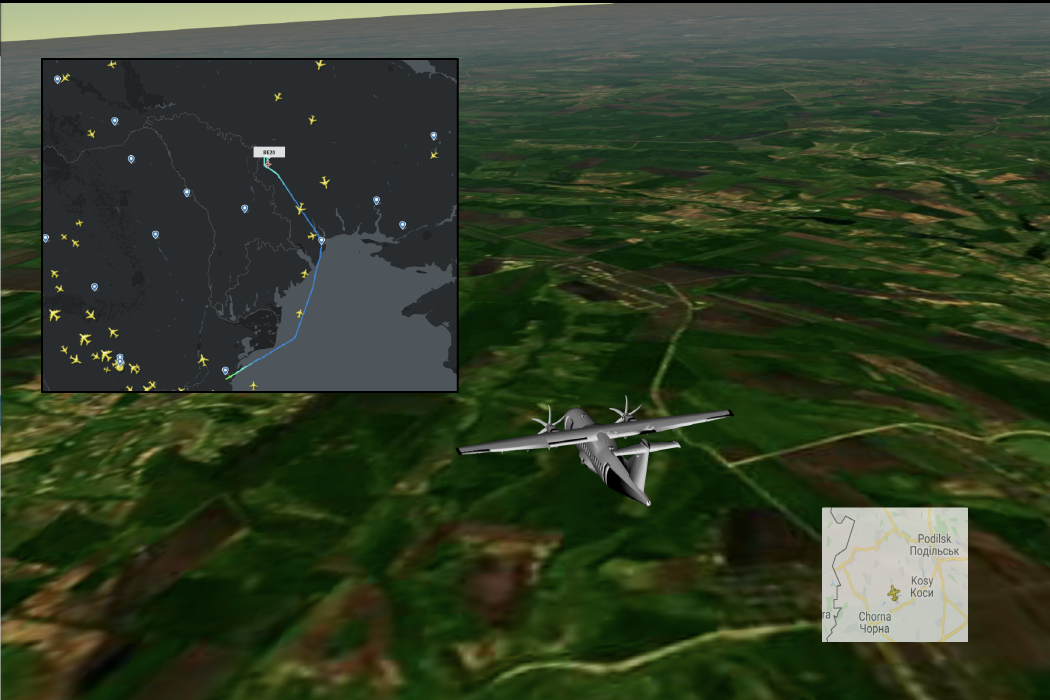

6. Russia’s logistical capacity around Ukraine is difficult to estimate at this point. The most recent authoritative estimate comes from a U.S. government source (quoted by CNN on 3 December 2021): “current levels of equipment stationed in the area could supply frontline forces for seven to 10 days and other support units for as long as a month.” Russia’s current logistical capacity is now likely more extensive than in December.

#Russia|n railways on Jan 15 2022.

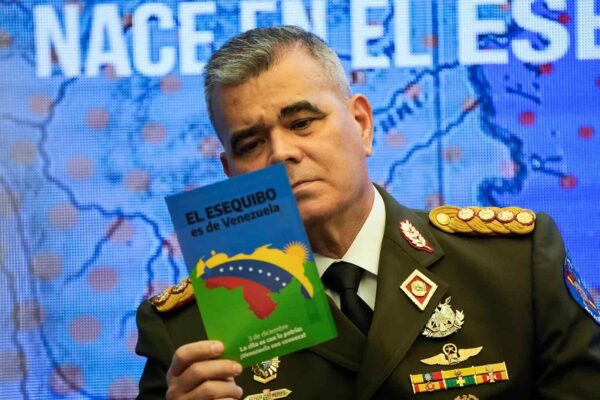

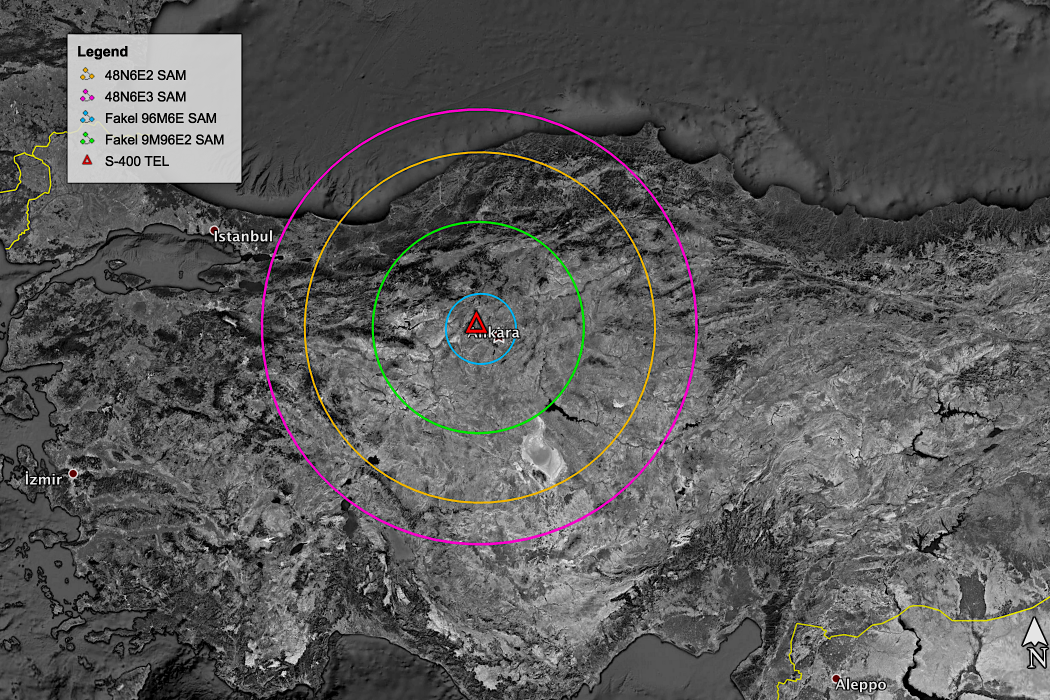

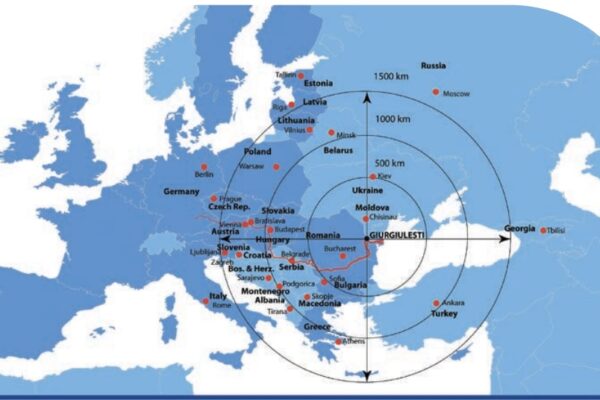

Transportation of logistics vehicles. pic.twitter.com/8H9usMk0tY

— 🅻-🆃🅴

🅼 (@L_Team10) January 15, 2022

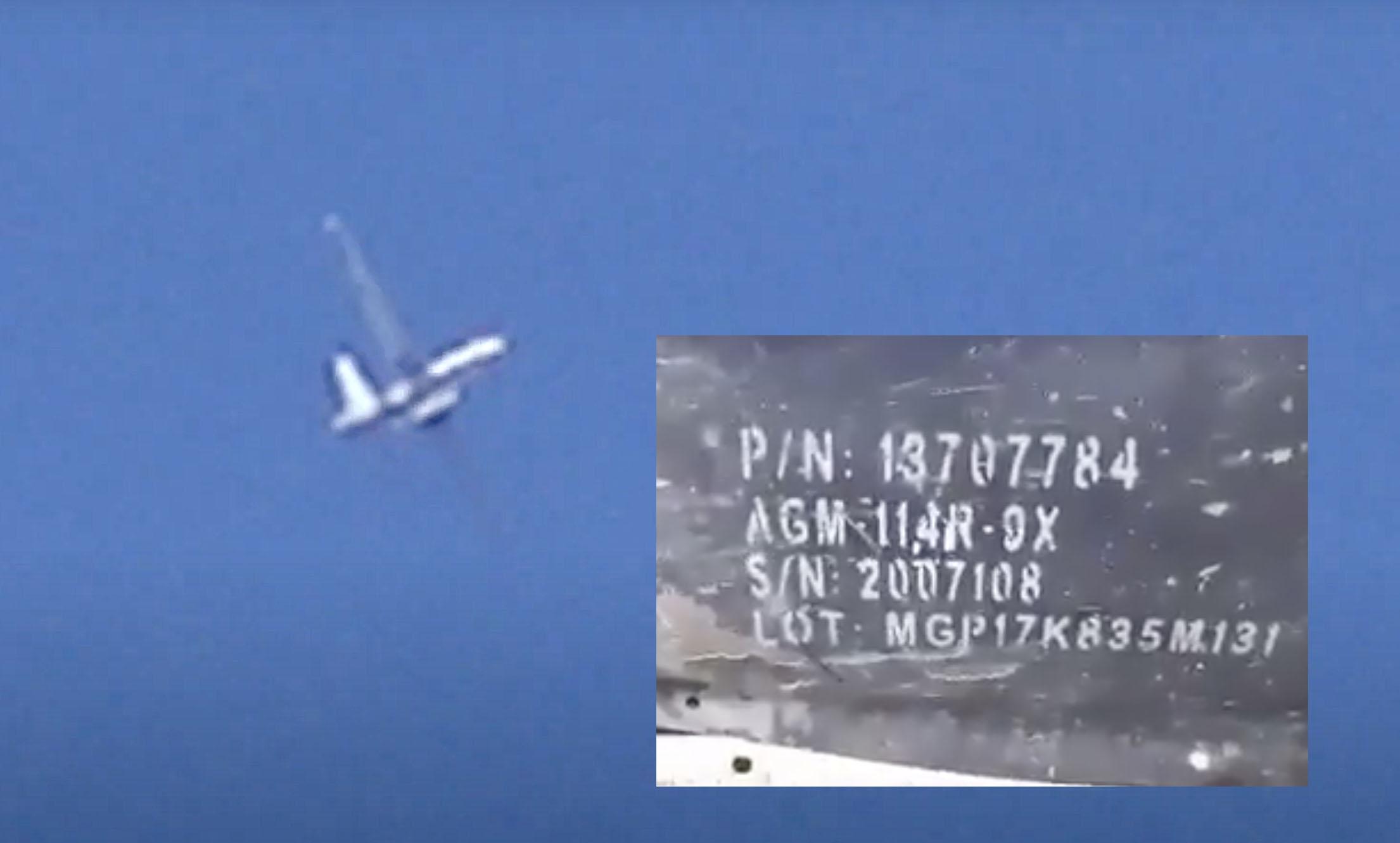

Logistics trains like this is something you don’t see with normal exercises.#Russia https://t.co/d5dTTIedXL

— Petri Mäkelä (@pmakela1) January 17, 2022

Major logistics, supply and fuel train moving through Tyumen, Russia, posted on TikTok 9 hours ago pic.twitter.com/eqkjdEoJxN

— ELINT News (@ELINTNews) January 21, 2022

7. Russia’s logistical build-up is likely incomplete and will certainly continue at least until February 10-20, when joint exercises will take place in Belarus. With no “Z-Day” in sight, troop movements and supplies will probably continue beyond February – if not to boost to sustain the Russian military capacity. A CITEAM social media analysis found that most soldiers are expected to be deployed for two to seven or even nine months.

While unnecessary for a show of force, logistics are a prerequisite for military operations. Tanks cannot move without fuel from tankers; soldiers cannot receive food and ammunition without utility trucks supplying the frontline; combat injuries must be treated in field hospitals.

EFFORTS TO CONCEAL

8. Unlike during previous “bear scares,” Russia has made significant efforts to conceal the troop movements and boost operations security (OPSEC). Countermeasures include nighttime movements, blacking out unit markings, covering equipment, disrupting online tracking methods (such as railcar databases), and dispersing staging areas in smaller formations. This behavior starkly contrasts the build-up in March and April 2021, when the Russian posturing was overt and demonstrative.

FIVE OPERATIONAL DIRECTIONS (OD)

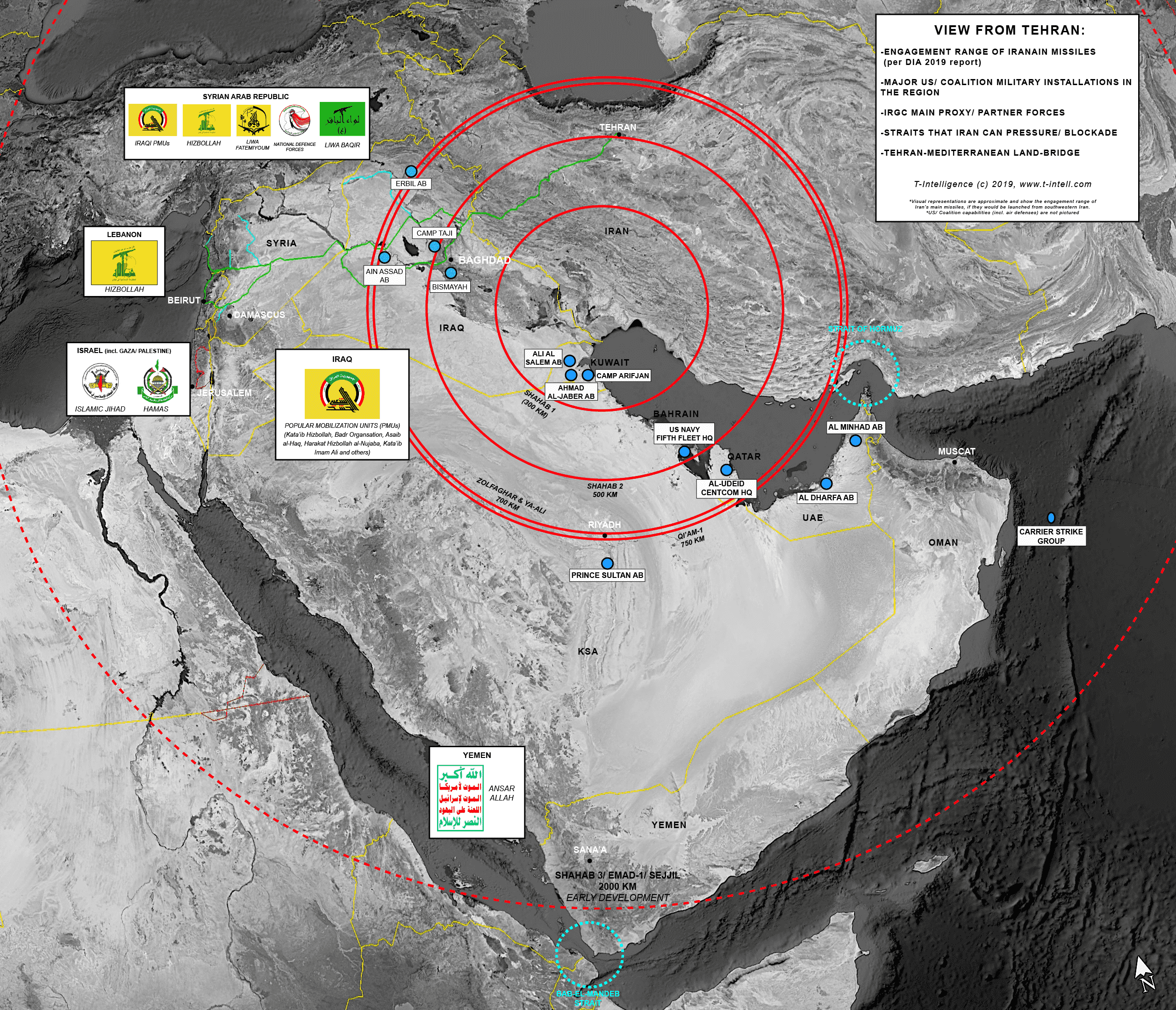

9. Russia has positioned its forces along five axes of attacks, or operational directions (OD)*, around Ukraine: Belarus, Yelnya, Orlov-Voronezh, Don, and Crimea. The following is a short account** of Russian troop dispositions in the five ODs, their relevance, and possible objectives.

Map shows the Ukraine military intelligence assessment of possible Russian attacks paths (source: Ukrainian military/Military Times)

*axis of attack launched from a given staging area, as seen in a Ukrainian Military Intelligence map released in a Military Times interview November 2021.

**For an extensive and detailed overview of the Russian order of battle in these areas, please refer to Rochan Consulting’s Tracker, from which most of this data is drawn.

BELARUS OD

a. The latest and most important piece of the jigsaw puzzle assembled around Ukraine. OD Belarus brings Kiyv within striking distance of Iskander-M SRBMs. Due to its proximity to the capital (150-200 km), OD Belarus can serve as a springboard for an offensive on Kiyv.

Russian Iskander missile systems in Asipovichy, Belarus. pic.twitter.com/c2t2RGPgfI

— Benjamin (@hengenahm) January 21, 2022

b. Currently, there are seven to ten BTGs in Belarus, mainly from the EMD, according to Rochan Consulting. Russian infantry and mechanized units have been documented arriving in large numbers in Mazyr, Recyca, Gomel, Yelsk (18 km from UKR border), and the surroundings.

Russian troops have officially arrived in the Belarusian town of Yelsk, 18km from Ukraine. A local news outlet made a short story about it. pic.twitter.com/ZdprX1a8Th

— Tadeusz Giczan (@TadeuszGiczan) January 20, 2022

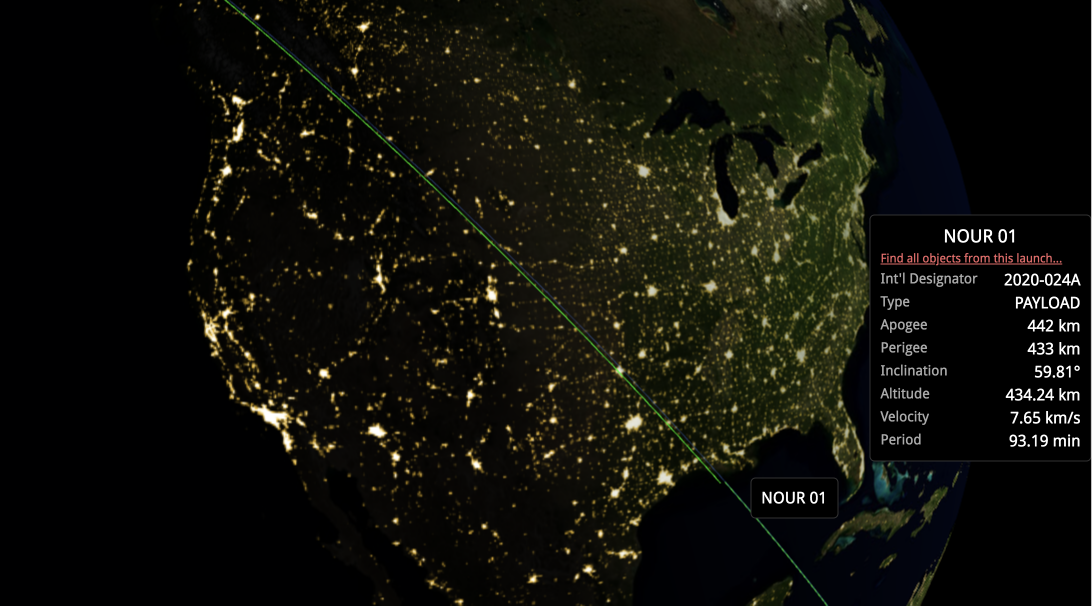

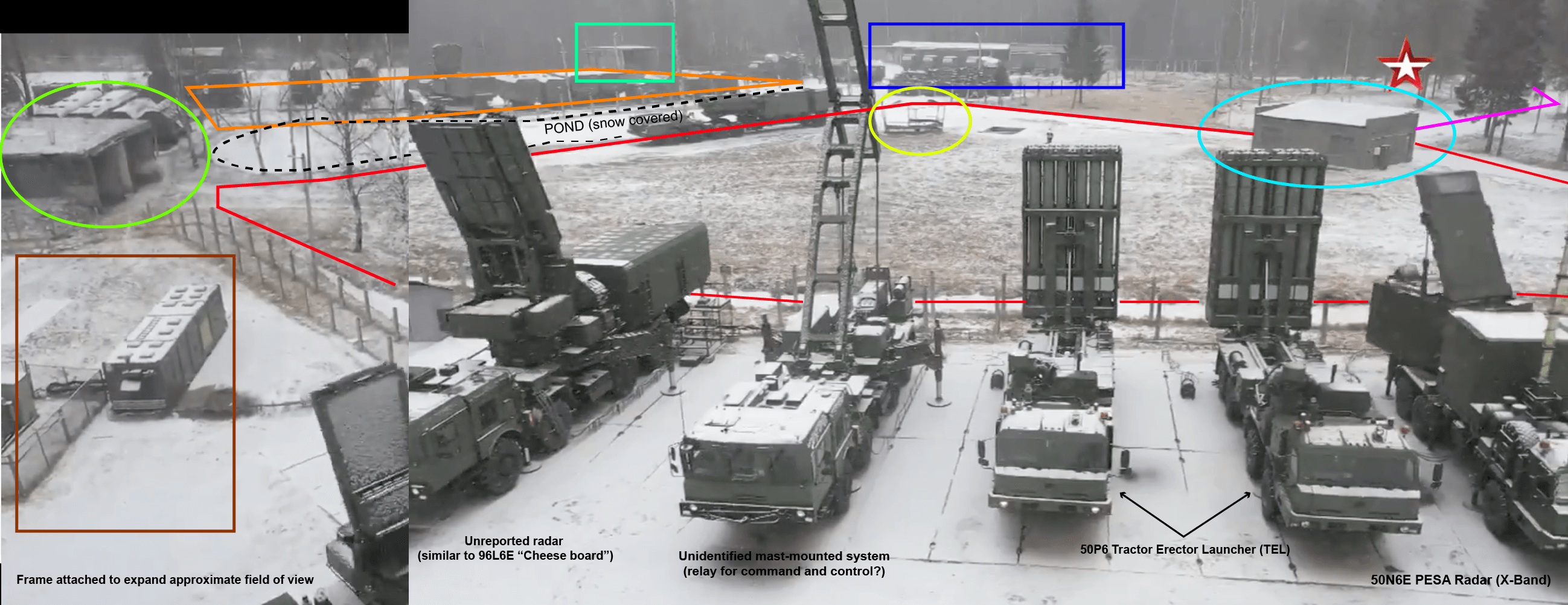

c. Troop movements towards Belarus began sometime in early January and are escalating. A Su-35 squadron has left its homebase inKomsomolsk-on-Amur (near the Sea of Japan), and will soon touch down in Belarus. Two S-400 surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems will follow shortly. Iskander SRBMs are also reportedly joining the party.

YELNIA OD

a. The forces headquartered and amassed around Yelnya could support OD Belarus and OD Orlov-Voronezh with reinforcements or open a new axis of attack to stretch UKR forces thin in the north. Around four to eight BTGs are based in OD Yelnya, with many units assuming positions close to the tri-border with Belarus and Ukraine at Klintsy. With the influx of an Iskander battalion (approx. 24 missiles) from the 119th Missile Brigade, and various multiple rocket launcher systems (MRLS), OD Yelnya also packs firepower with range to strike Kiyv.

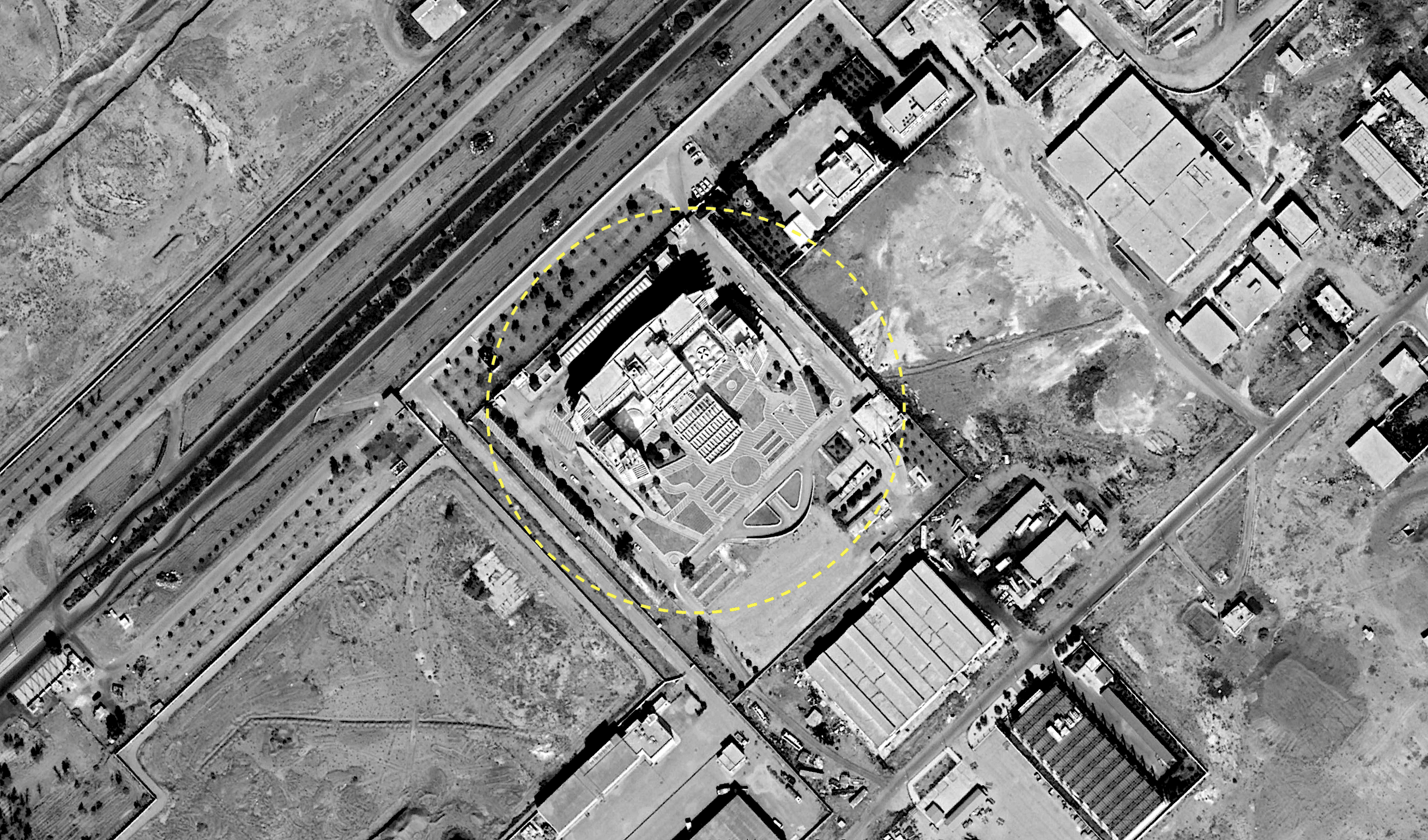

Russian military presence at a staging ground near Yelnya. Image captured on 19 January 2022 by Maxar Technologies.

ORLOV-VORONEZH OD

b. Established during the initial build-up in March and April 2021, these forces pose a direct threat to Ukraine’s second-largest city, Kharkiv, and the adjacent areas. There are likely at least twelve BTGs concentrated between Orlov and Voronezh, and these forces have been kept at high readiness through drills simulating nighttime assault and artillery support.

Pogonovo training ground. Imagery captured on 16 January 2022 by Maxar Technologies

c. Pogonovo and Krynitsa training grounds are the epicenters of the manpower concentration in this OD. Since last year’s “bear scare,” Pogonovo has been exceptionally well documented via satellite imagery (see our analysis) and remains an area of primary concern (see Rochan Consulting’s GEOINT analysis). The forces and equipment at the two staging grounds augment the formidable 20th Combined Arms Army (CAA) headquartered in Voronezh.

d. In the past weeks, units in this OD have inched increasingly closer to Ukraine’s border. Satellite imagery from December 2021 shows an increase in military hardware in Valyuki/Soloti, just 15 km from the Ukrainian border. Similar activities have been noted in Baguchar (80 km), amounting to a worrying trend.

Satellite imagery from the 9th of December showing a large collection of RU Military Hardware near #Valuyki: just 15 km from the border with Ukraine. https://t.co/2MlgppdGIC pic.twitter.com/PgkEmgIsjp

— The Intel Crab (@IntelCrab) December 18, 2021

DON OD

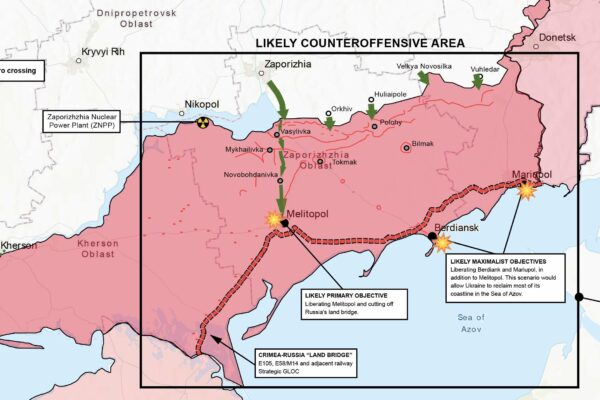

a. Over 15 BTGs inhabit the areas between Rostov-on-Don and Ndvocherkassk. Their potential role will be to rendezvous with Russian forces stationed in eastern Ukraine to strengthen local defenses or help mount an offensive in depth. Hypothetical offensive operations will likely seek a breakthrough in Mariupol followed by a march along the Azov coastline. Don OD could also eye the Dnieper river valley, especially in a joint operation with splinter formations from Orlov-Voronezh OD.

CRIMEAN OD

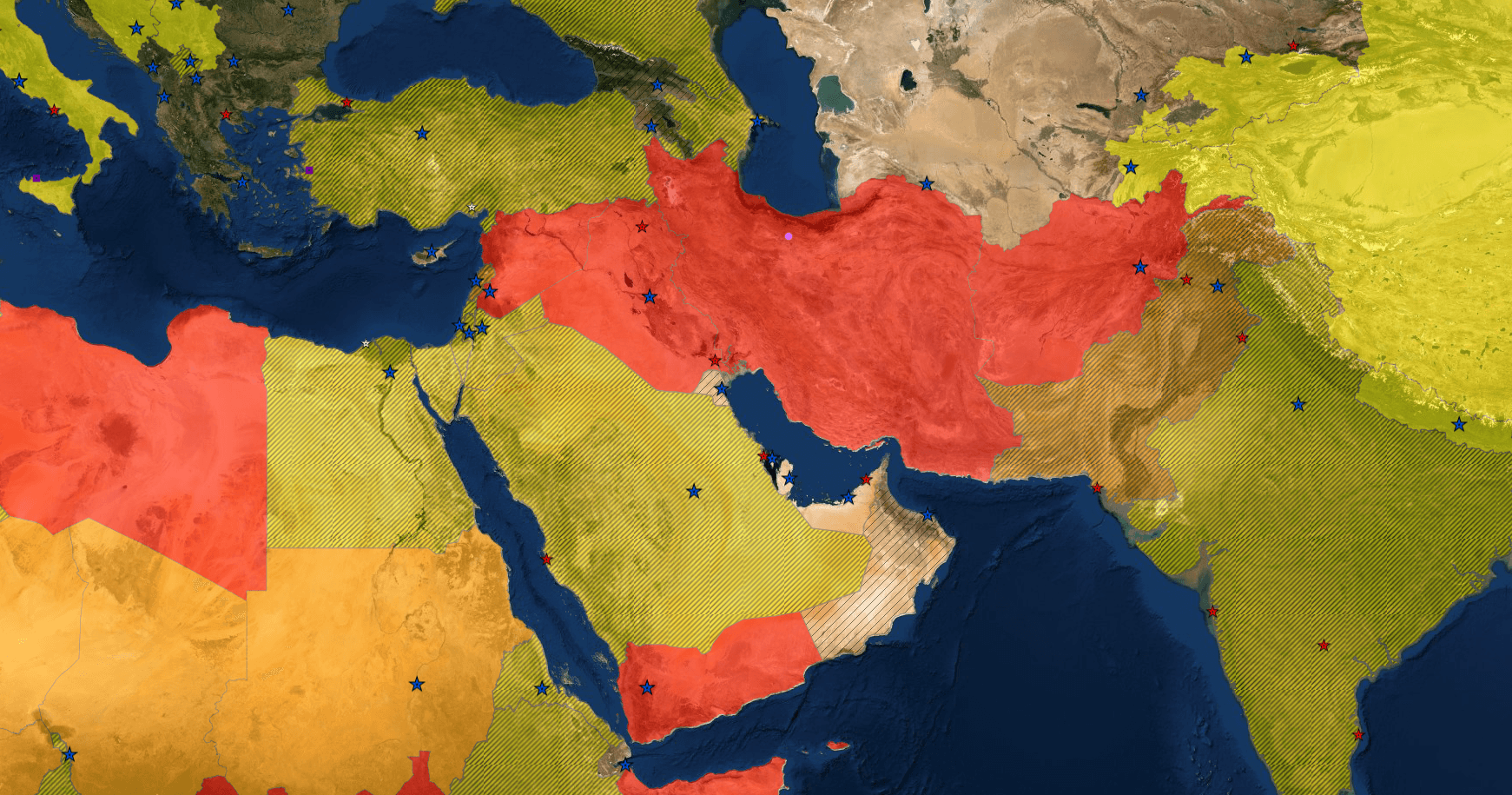

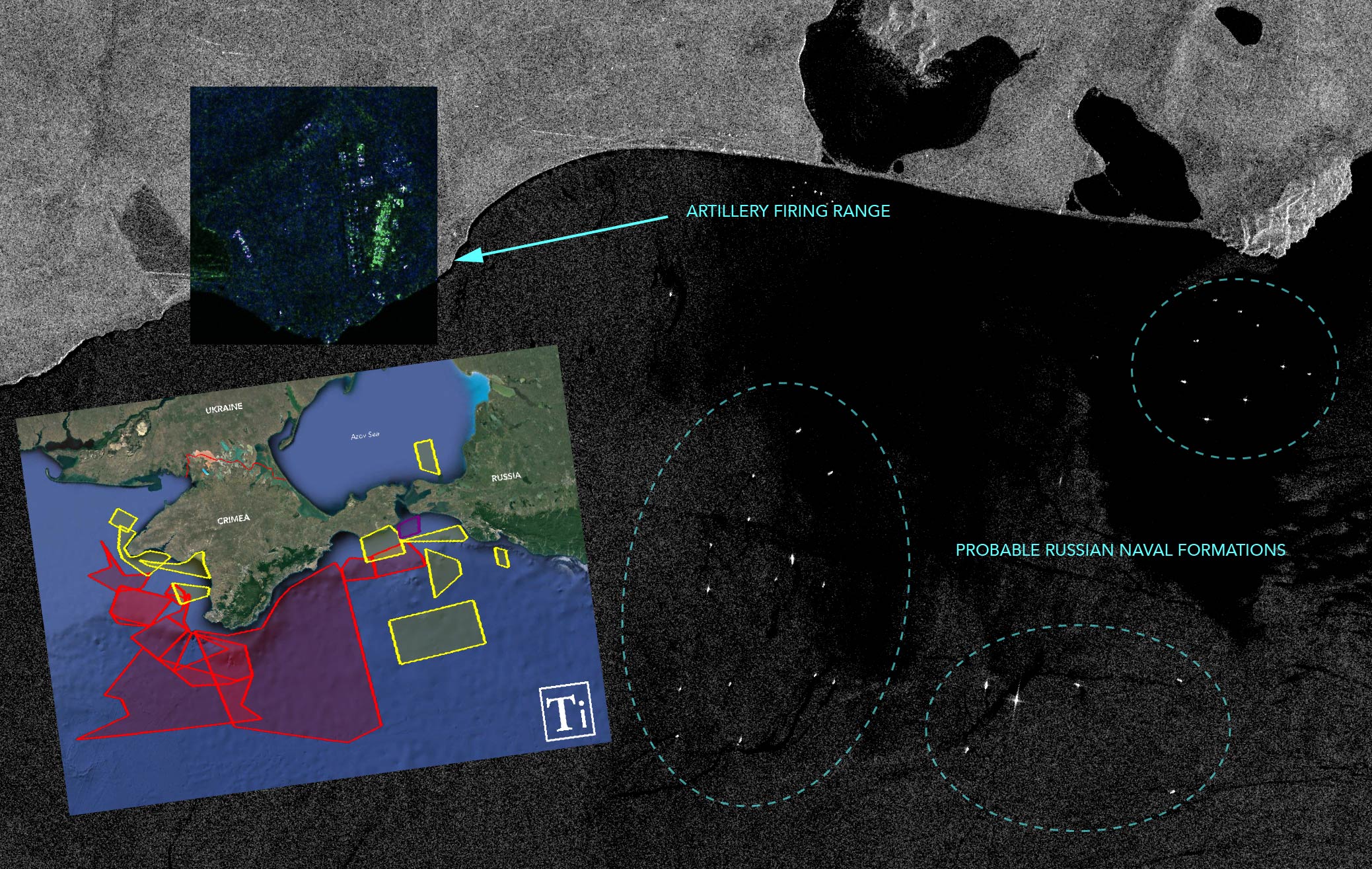

a. This OD could open no less than three axes of attacks on Ukraine’s coastline. An amphibious assault launched from Crimea’s western coast would target Odessa and the adjacent littoral. Once ashore, these forces could link up with the Operational Group of Russian Forces (OGRF) from the Transdnister breakaway republic coming from the west. The lower section of the Dnieper valley (North Crimean canal) is another realistic, although overstated, target. Together with Don OD, Crimea-based forces would likely also attempt a pincer movement on the Melitopol-Mariupol axis.

b. Russia has simulated almost all of these attack scenarios during the military build-up in March and April 2021, during which new BTGs assumed permanent stations in Crimea, bringing the total count to at least 12 BTGs. Back then, the main event was a major amphibious assault on the Opuk training range, which we documented in this analysis. Air and infantry assaults around Dzankhoi and other areas in northern Crimea were also noteworthy.

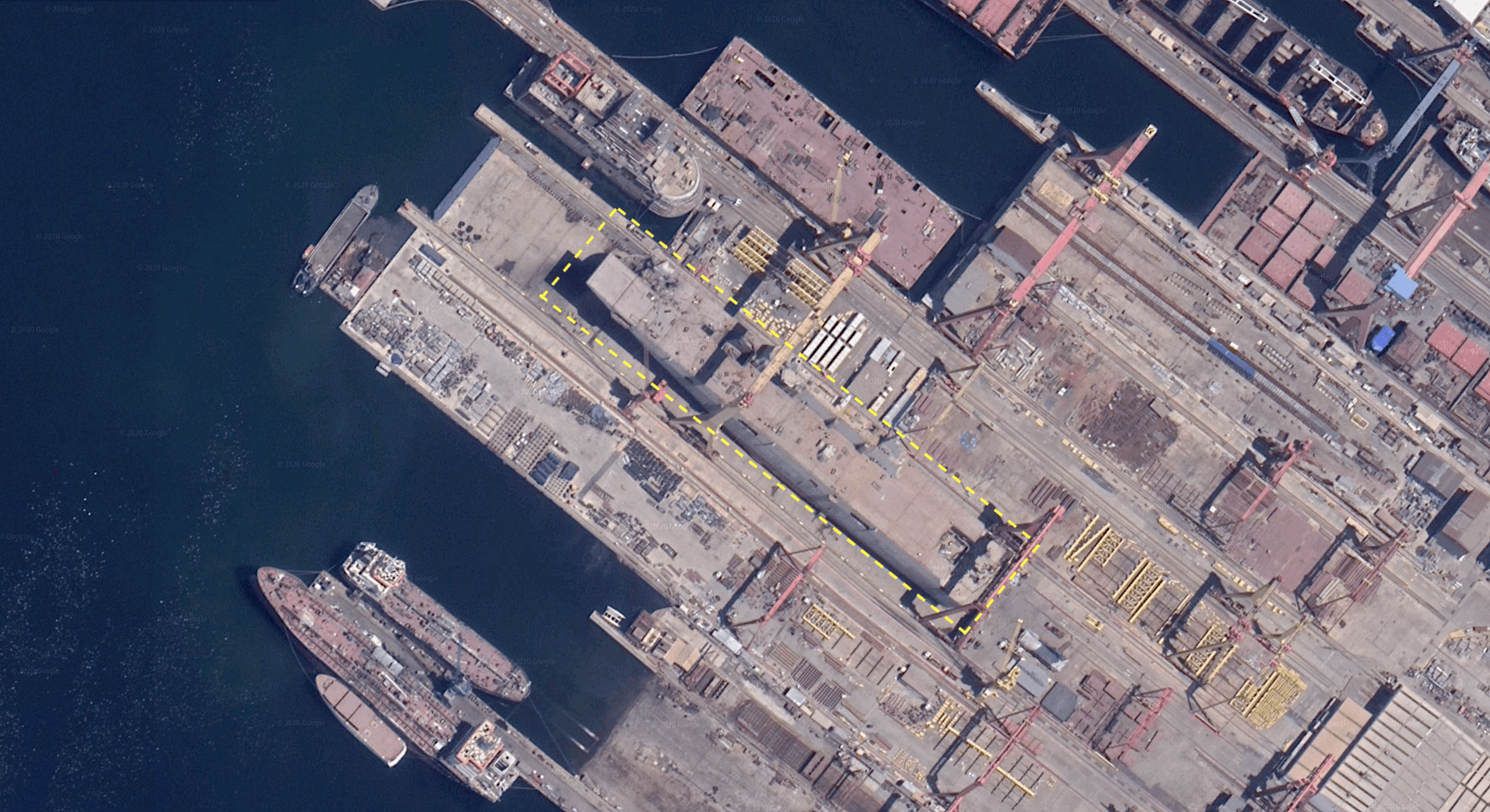

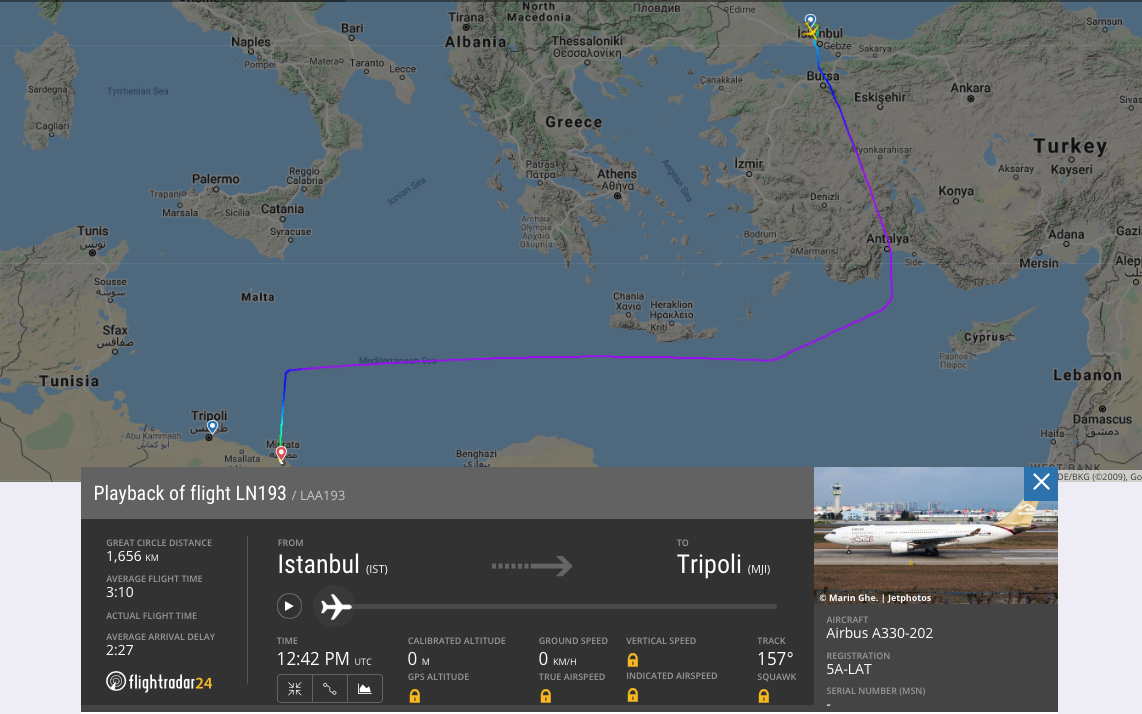

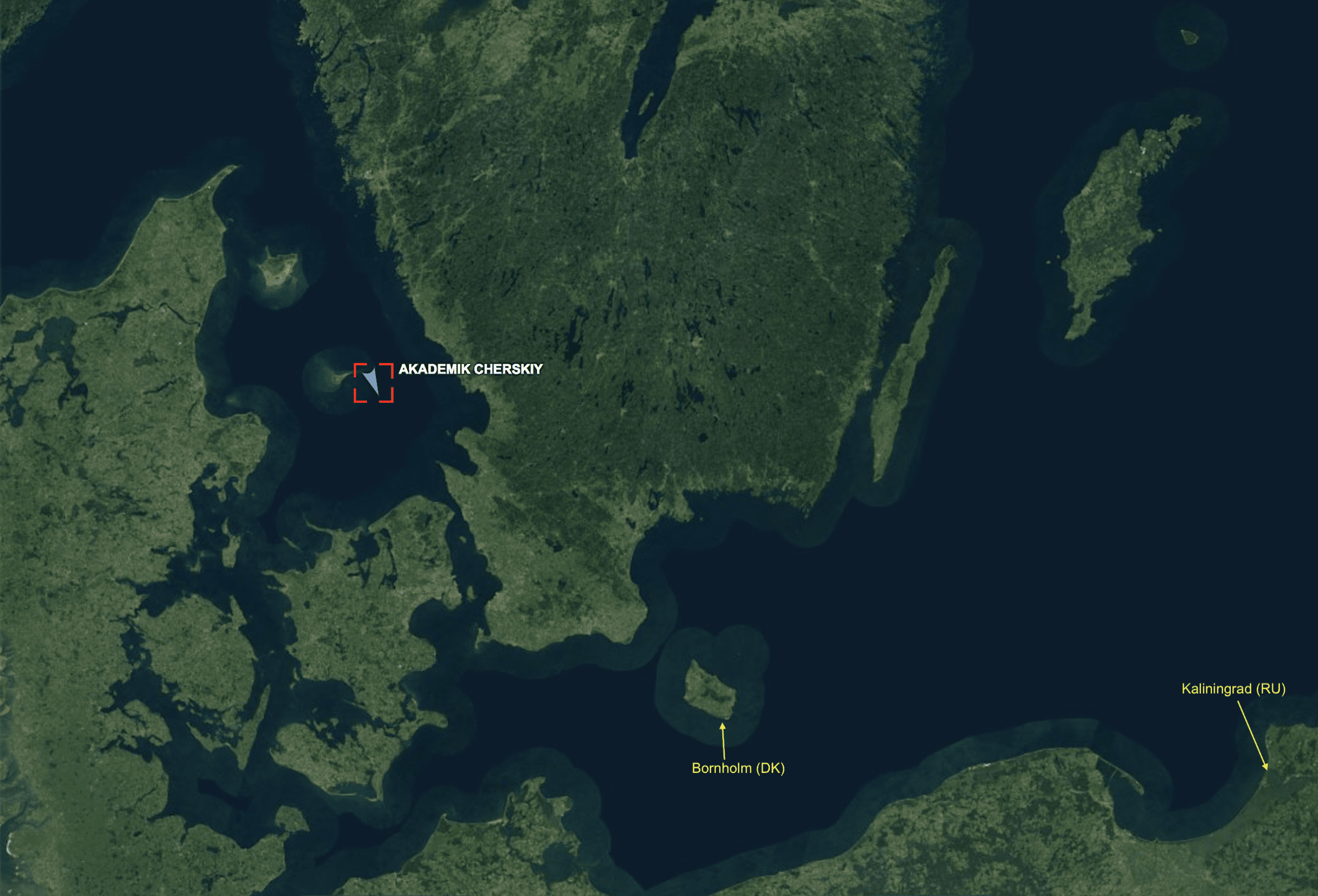

c. Naval movements are also underway, with a task force comprising of Baltic Fleet and North Fleet vessels (including three Ropucha-class landing ships) heading towards the Mediterranean Sea to link up with Pacific Fleet ships for joint exercises. There are fears that at least a part of the maritime task force will enter the Black Sea.

Russia deployed the largest naval and amphibious grouping to the Black Sea in April since the fall of the Soviet Union with 4 large landing ships from the Northern and Baltic Fleets. It appears they’re about to deploy even more this time. 675/https://t.co/9KTnPQJDoo

— Rob Lee (@RALee85) January 20, 2022

INTENTIONS & AIMS

10. Russia’s intentions remain unclear, but we judge the likelihood of direct action high with a 55 to 60% confidence level. Our estimates are based on the build-up’s unprecedented scope and credible composition, including the multi-axis posturing and the unachievable, maximalist political demands of Russian diplomacy.

11. It is unknown how the hypothetical military operation will look. While the Russian military is positioned for a multi-axis assault, it will not necessarily follow the apparent blueprint. Russia might seek to activate only one OD, such as Belarus or Voronezh, a combination of them, or all. Attacks could be simultaneous or gradual and will fluctuate based on the situation on the ground.

12. The hypothetical campaign will likely be punitive, target Kyiv or Kharkiv, and seek to install or facilitate the emergence of a Russian-friendly “salvation” government. Such an operation would be akin to the 2008 Georgian campaign, where Russia did not seek to annex territory but to force the government into submission. Rob Lee put forward a similar hypothesis in an extensive article here.

13. There is also a high possibility (40 to 45%) that no military operation will occur, yet heightened tensions will persist. The build-up could proceed and even escalate, but hold out for months. As a result, more units will permanently or semi-permanently entrench near Ukraine, waiting to achieve strategic surprise later. The payoff could come even seven months into the future. Alternatively, a significant amount of forces could pack up and return to their home base at any given moment.

14. Russian President Vladimir Putin will make the final decision. While “Kremlinologists” have long tried to interpret the thoughts of Kremlin leadership, nobody knows Putin’s calculus. He has likely committed to one or several courses of action, hence the comprehensive preparation, but the final order has not been signed and issued.

RUSSIAN MOTIVATIONS

FEARS OF IMPENDING UKRAINIAN OFFENSIVES IN DONBAS

15. The key driver of this build-up is the perceived threat of a Ukrainian offensive to recapture Donetsk and Luhansk and the increased anti-Russian narratives of the Zelensky administration. Past events (see below) might have forced Russia to consider that the current democratic order will not generate a pro-Russian government in Kiyv. Recapturing Donbas and pursuing NATO membership will remain a top priority of all upcoming cabinets.

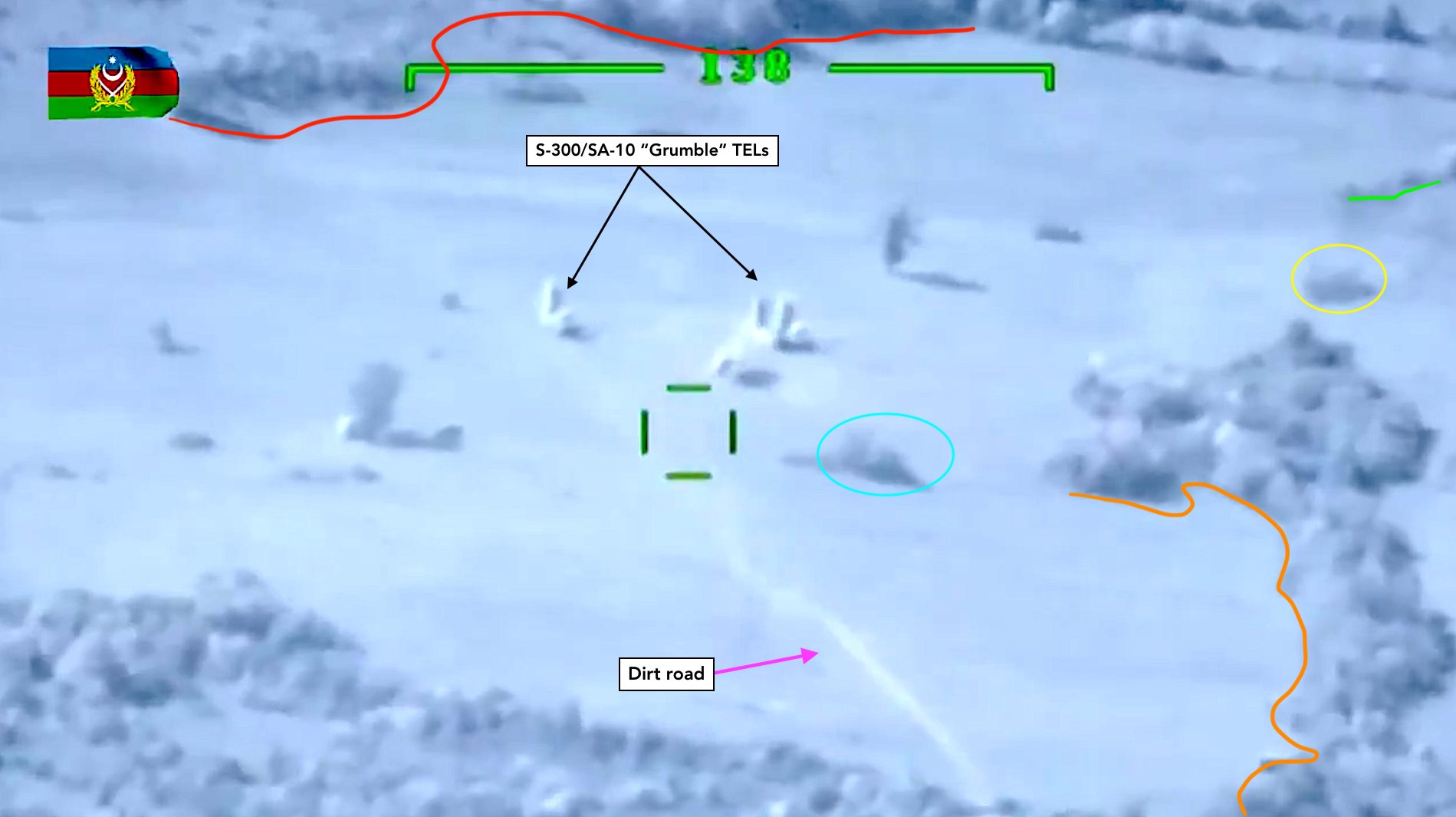

a. THE DRONE STRIKE: On 26 October 2021, a Ukrainian Bayraktar TB-2 drone bombed a Russian artillery position in Luhansk. The artillery system had passed the withdrawal line of the Minsk agreement and shelled Ukrainian positions. This was the first Ukrainian airstrike on a Russian position and arguably Kiyv’s most hawkish action in years. Russia reacted by resuming and escalating the build-up of March to April 2021, leading to what we see today.

b. THE PERCEIVED UKRAINIAN BUILD UP: Between late 2020 and early 2021, a string of videos online apparently showed Ukrainian tanks on railcars rushing towards eastern Ukraine. Whether this was a build-up or just a rotation of the forces stationed near the frontline remains unclear. However, Russia decried the troop movements as preparation for an offensive in Donbas. In retaliation, Russia escalated the conflict in Donbas and initiated the build-up of March and April 2021.

c. ZELENSKY TURNS HAWKISH: Ukrainian President Zelensky initially adopted a de-escalatory agenda regarding Donbas and pursued peace talks with Russia. By 2020, it became apparent that Russia had no interest in entering negotiations with Ukraine until non-starter demands, such as Ukraine renouncing NATO membership and sovereignty over Donbas, were met. As Zelensky’s dovish strategy failed to bear fruit, his public approval started plummeting. As a result, he adopted a more hawkish demeanour, taking action against Russian-backed opposition, seeking to re-energize ties with NATO, and invigorating Ukrainian aspirations in Donbas. Russia took note of the change of tone and started viewing Zelensky as a problem.

SECONDARY CONSIDERATIONS

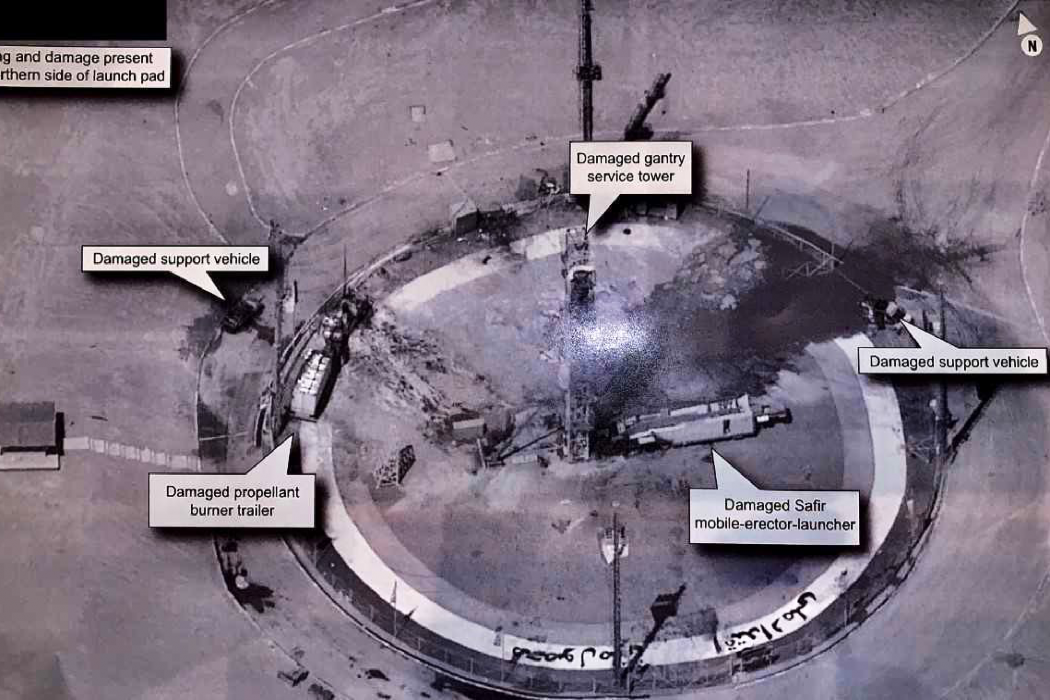

16. Modernization and growing capabilities of the Ukrainian Armed Forces render Kyiv an increasingly potent adversary. Tactical assets like the Bayraktar drones and Javelin anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs) cannot generate strategic advantages, but ballistic missiles and cruise missiles can – if stockpiled in high enough numbers. Ukraine is currently developing the Hrim SRBM (with covert funding from Saudi Arabia) and Neptune anti-ship cruise missiles. These two assets can pose a credible threat to Russian critical infrastructure, command and control centers, and population centers, raising the cost of aggression for Moscow. Other programs such as unit reform or NATO training and standardization will also improve Ukrainian combat effectiveness.

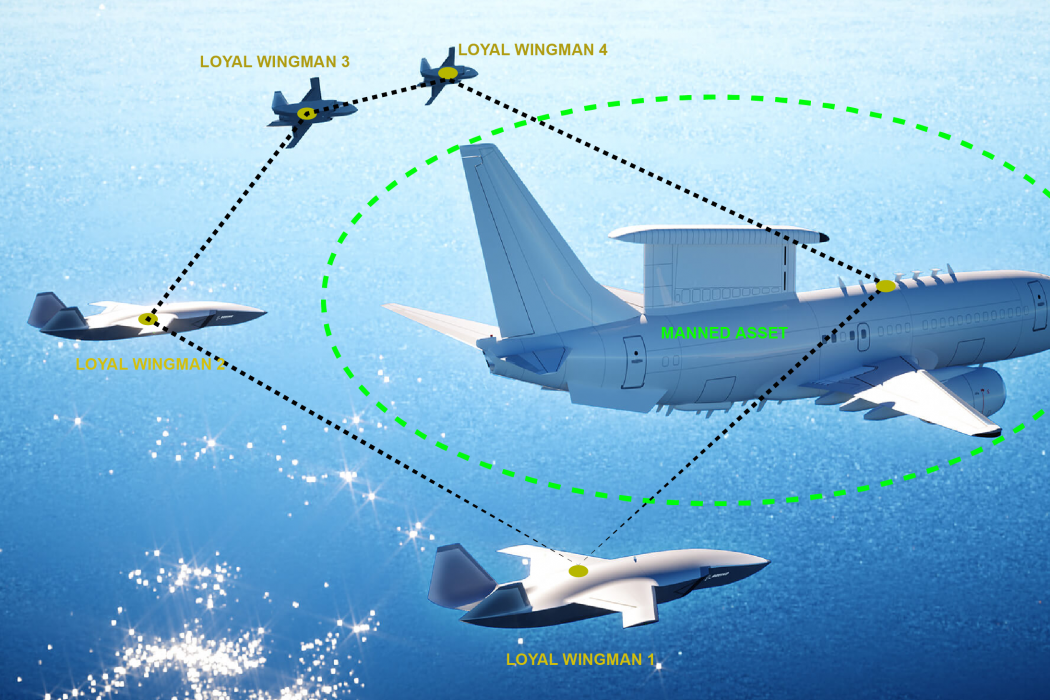

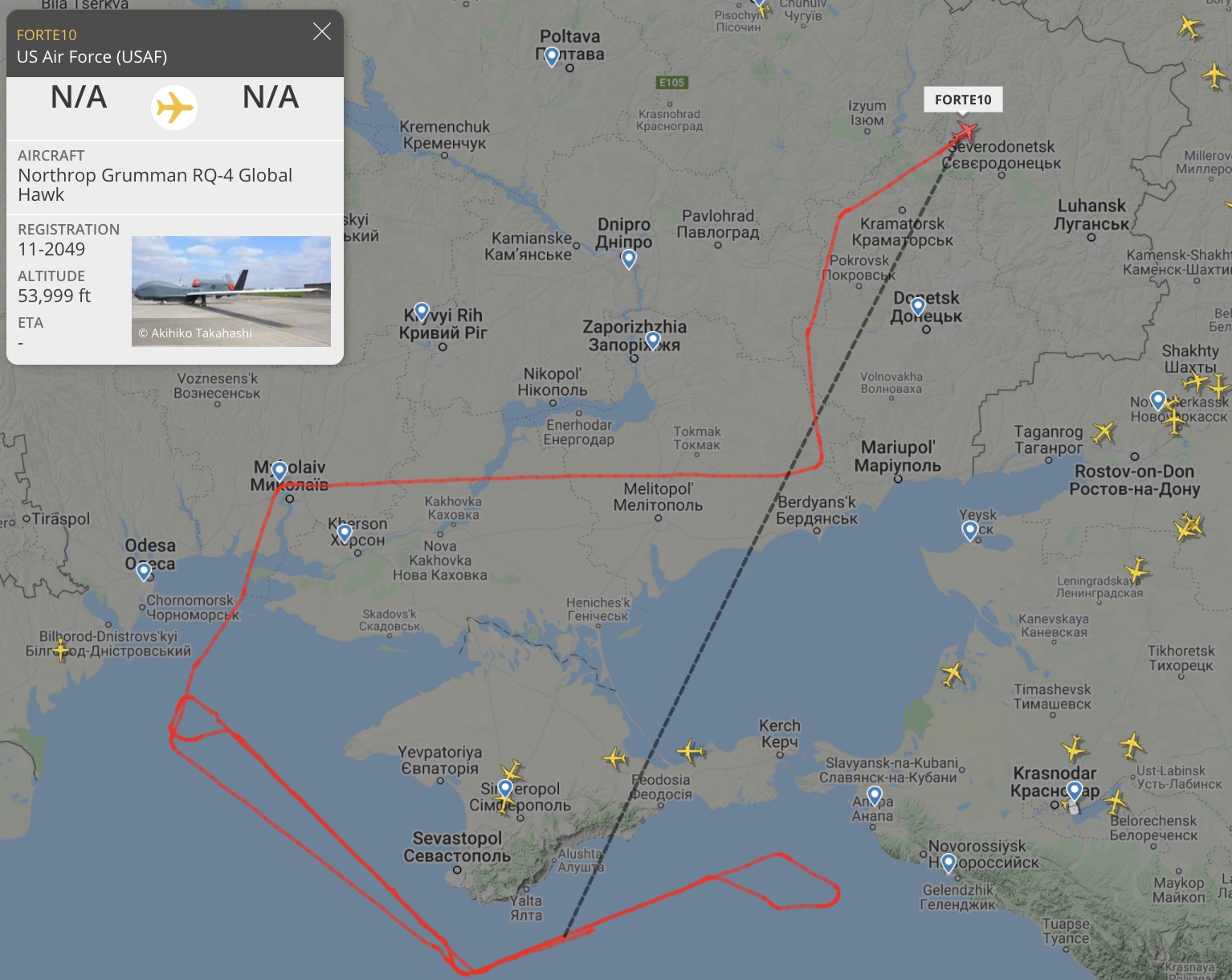

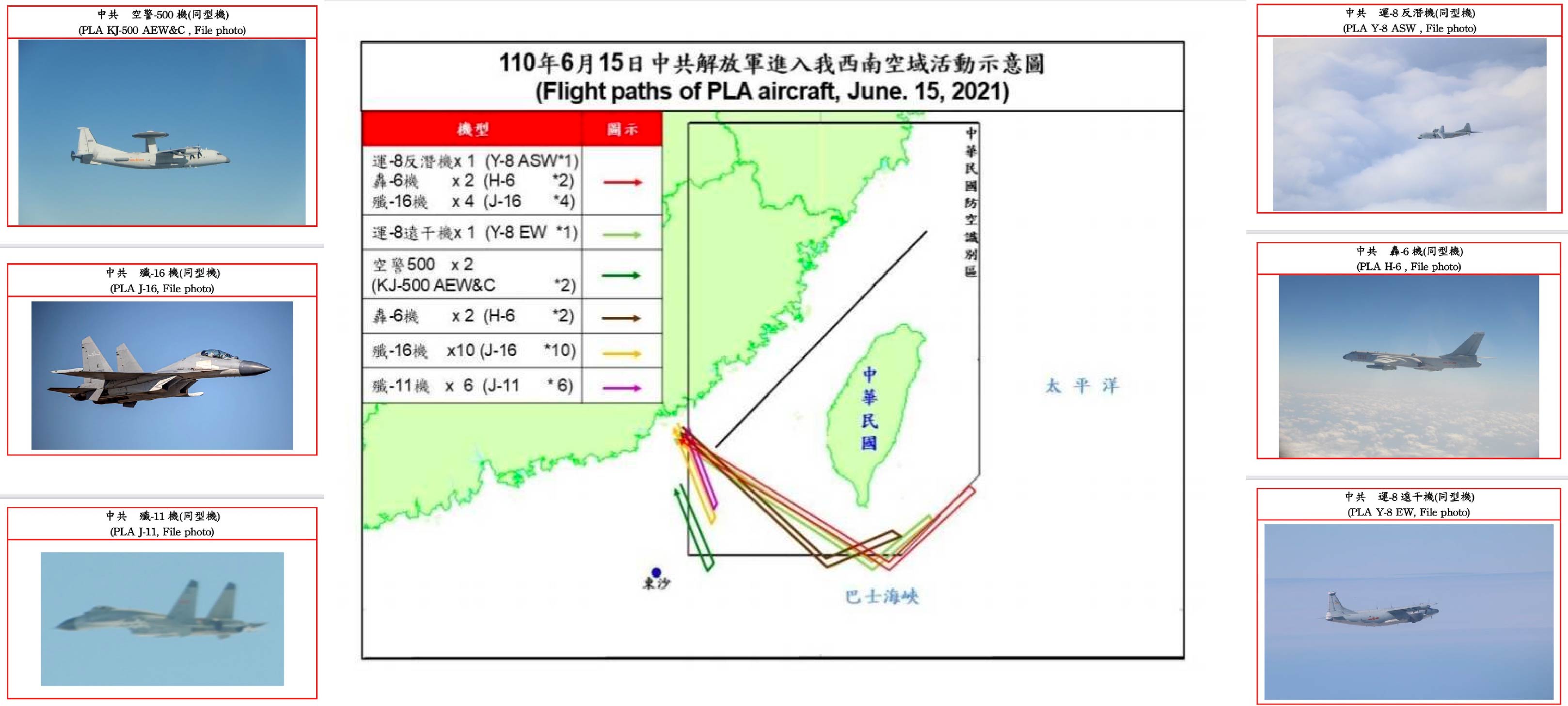

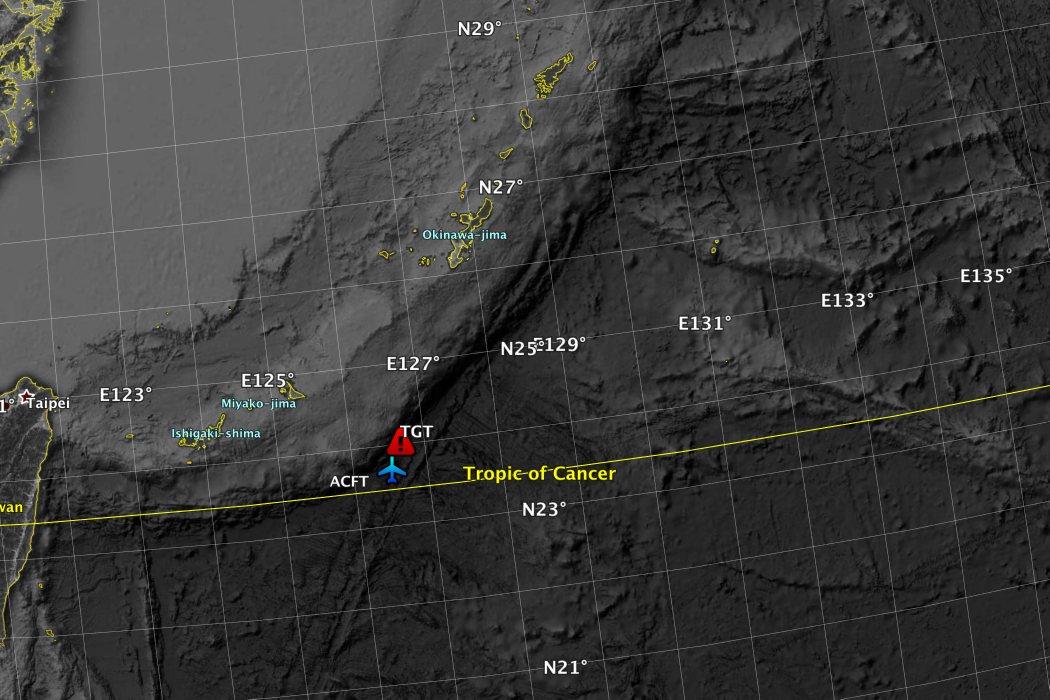

17. NATO Reconnaissance sorties over Ukraine keeping a watchful eye on nefarious Russian activity. Russian officials have publicly decried the constant sorties of NATO reconnaissance aircraft tracking their movements in Donbas and the Black Sea. American Global Hawk drones, P-8A Poseidons, various RC-135s and various other ISR aircraft patrol the region daily and could provide early warning of a Russian invasion and expose the movements.

Earlier today, ten ISR aircraft from multiple NATO members flew over the Baltics and Ukraine:

USN P-8A (PK18x)

US Army RC-12Xs (YANK01 & YANK03)

USAF RC-135W (JAKE11)

USAF E-8C (REDEYE6)

RAF P-8A (GURNY01)

RAF RC-135W (RRR7205)

Swedish S100D (SVF604)

Swedish S102B (SVF623)

1/5 pic.twitter.com/bvRF4D7MXs— Amelia (@ameliairheart) January 18, 2022

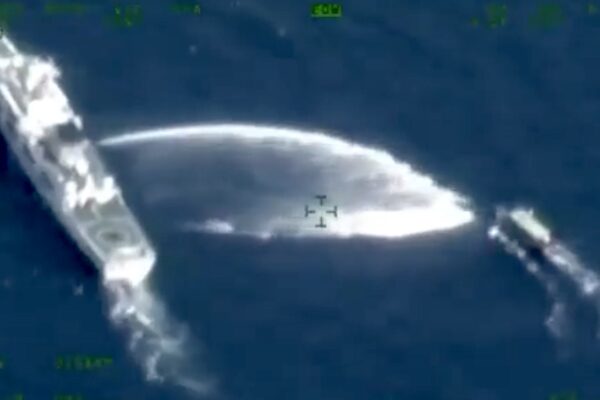

18. Growing defense ties between Ukraine and individual NATO members. Similarly, Russia is unhappy with the maturing defense ties between Ukraine and various NATO members, especially the United Kingdom. Ukraine and the United Kingdom have signed a defense agreement in mid-2021, which was followed by a significant incident at sea involving the HMS Defender and a Russian naval task force (see our analysis on the topic). While Ukrainian NATO membership remains impossible at this point, Russia is taking note that individual NATO members are coming to Kiyv’s aid.

DIPLOMACY: THE INFORMATIONAL COMPONENT

19. Moscow’s diplomatic campaign around the build-up serves the informational offensive against NATO. Leveraging nonmilitary means, namely political and information warfare, is a tenet of the Russian General Staff’s approach to “new generation warfare.” Russia’s official demands include guarantees that Ukraine will never join NATO, the withdrawal of NATO troops from Romania and Bulgaria, the decommissioning of the Ballistic Missile Defense system in Deveselu (Romania), and others. Russia does not seek a political settlement to the current tensions and is well aware that its maximalist demands are non-starters for the West. However, these political talking points serve to shift the blame for the current tensions on the so-called “NATO expansion.”

20. Western interactions with Russia’s false demands played into the Kremlin’s hands. Imprisoned opposition leader Alexey Navalny has perhaps captured the situation best in a TIME interview: “Instead of ignoring this nonsense, the U.S. accepts Putin’s agenda and runs to organize some meetings. Just like a frightened schoolboy who’s been bullied by an upperclassman.” Western diplomats should have rejected this rhetoric and brought the conversation back to the reality on the ground – the 100,000 Russian troops positioned to swallow Ukraine.

MEASURES TO DISCOURAGE ATTACKS & PALLIATIVES FOR THE DAY AFTER

21. Only the threat of massive economic sanctions can alter Russia’s war plans. Ironically, NATO’s most unreliable member, Germany, holds the biggest financial leverage against Russia. Nothing would deter a Russian invasion more than a credible threat from Berlin to terminate the North Stream 2 project. Perhaps equally important would be a concerted effort to disconnect Russia from the SWIFT payment system. American and EU targeted sanctions on Russian oligarchs will not affect military plans.

22. Wholesale transfers of tactical military equipment to the Ukrainian Armed Forces are necessary palliatives but do not deter a Russian invasion. Ukraine received over 1,000 NLAW ATGMs from the United Kingdom in the past few days. The British NLAWs will significantly boost Ukraine’s ATGM inventory, consisting of around 400 Javelins received from the United States, first under Trump (2017; 2018), then Biden (2020; 2021). Estonia will also deliver an unknown number of Javelins while Latvia and and Lithuania will donated Stinger man-portable surface-to-air missile systems (MANPADs) to Ukraine, in the next days.

передала #ЗСУ легкі протитанкові засоби

Це зміцнюватимеспроможності України, а надані засоби будуть використані виключно з оборонною метою pic.twitter.com/ipGpqPfInG

— Defence of Ukraine (@DefenceU) January 18, 2022

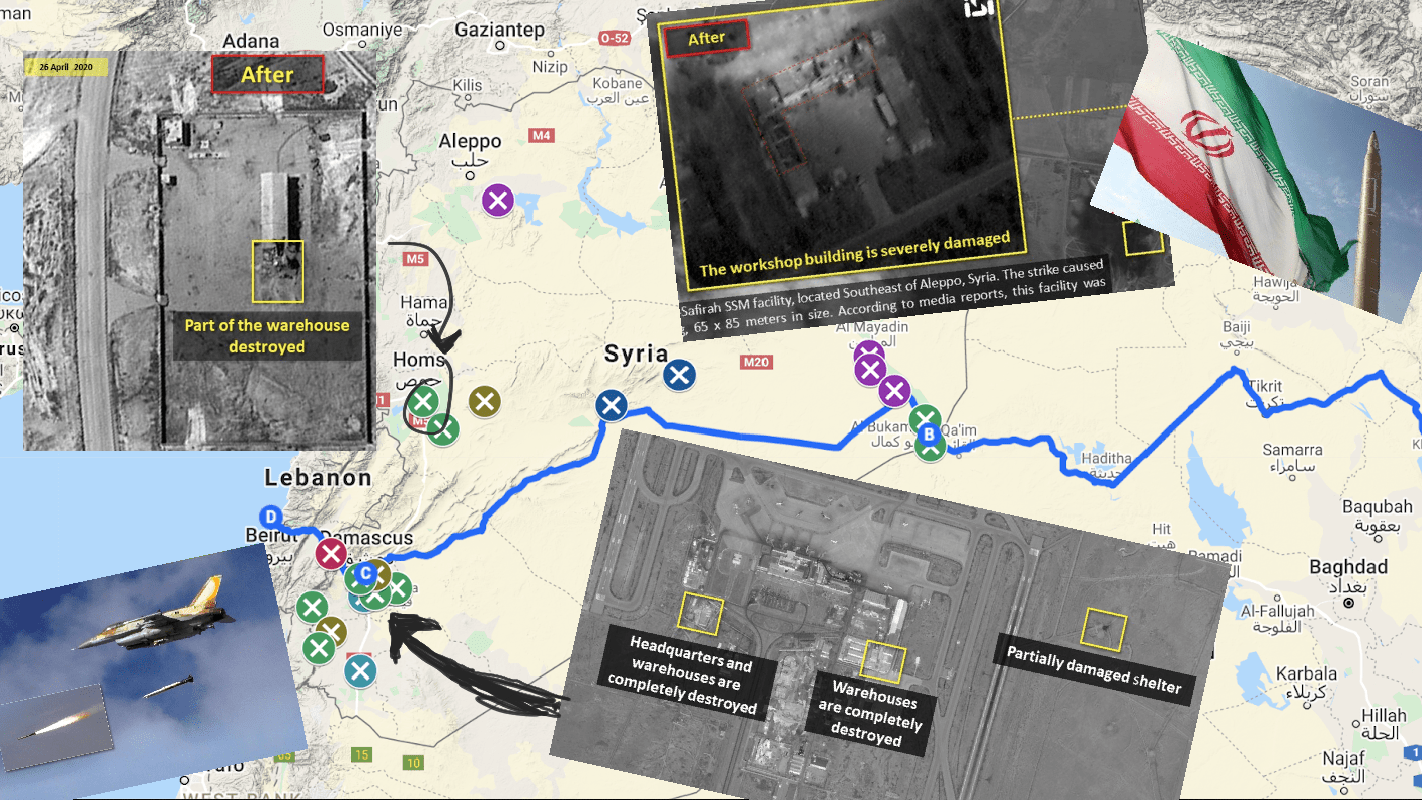

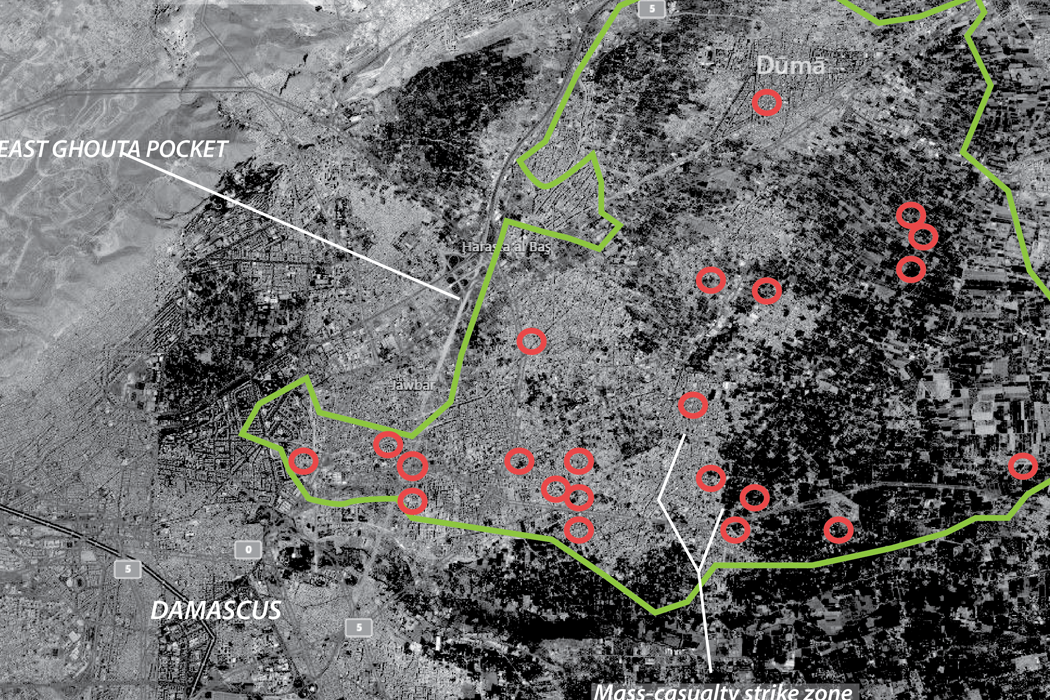

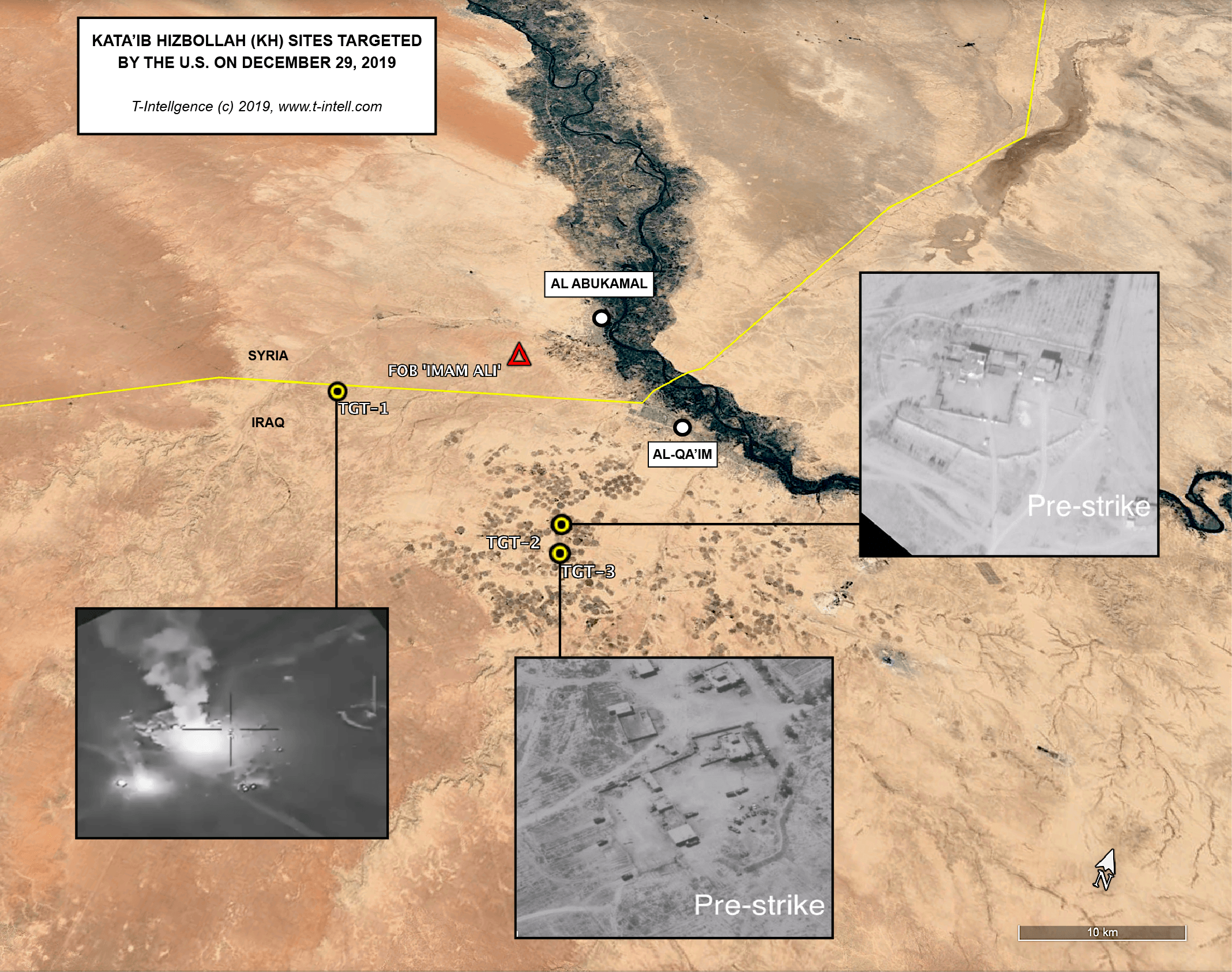

Ukraine’s growing stockpile of ATGMs will be critical to slow down an armored assault and impose costs on an aggressor but have no strategic value. Russia has likely already devised tactics to mitigate the ATGM threat using long-range fires, drone-directed artillery, and airstrikes, drawing from lessons learned in Syria. Alternatively, sabotage behind enemy lines is another course of action that Russia could take – and has likely already taken – to compromise ammunition depots.

NATO states should continue delivering military aid to Ukraine. The care packages should consist exclusively of easy-to-use equipment which can be quickly absorbed by the Ukrainian military and not require extensive training or high maintenance.

by Vlad Sutea

editing by Gecko

This assessment was made using Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) techniques and resources. Visit Knowmad OSINT to learn more about our online OSINT training.

Founder of T-Intelligence. OSINT analyst & instructor, with experience in defense intelligence (private sector), armed conflicts, and geopolitical flashpoints.

![Pride of Belarus: Baranovichi 61st Fighter Air Base [GEOINT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/cover_article.jpg)

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 2]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TelSalman24.2.2018_optimized.png)

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 1]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/KLZJan.62018copy_optimized.png)

![[UPDATED] Saudis To Retaliate After Iranian-Backed Drone Attack](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/copy-compressor.png)

![This is How Iran Bombed Saudi Arabia [PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/map4cover-01-compressor.png)