The following analysis is neither news nor a forecast, but a purely hypothetical assessment.

(a) If the situation in Venezuela escalates and Russia moves forward with its plans to establish a strategic bomber presence in the Caribbeans, it is not out of the question that the United States will step up its opposition to the Maduro government. The Trump administration, alongside the European Union and the large majority of Latin American states, already provide political support to the Juan Guaidó interim presidency. Currently, the rift between factions of Venezuela’s armed forces and the Maduro government are growing. Suspicious of his own security forces, Maduro reportedly hired Russian private contractors to provide additional VIP protection. Should the conflict turn into a civil war, the United States will likely support neighbouring allied countries such as Columbia. While National Security Advisor John Bolton is suggesting the idea of deploying 5,000 troops to Columbia, it is unlikely that such a plan is anything more than a psychological operation against Maduro and the Kremlin.

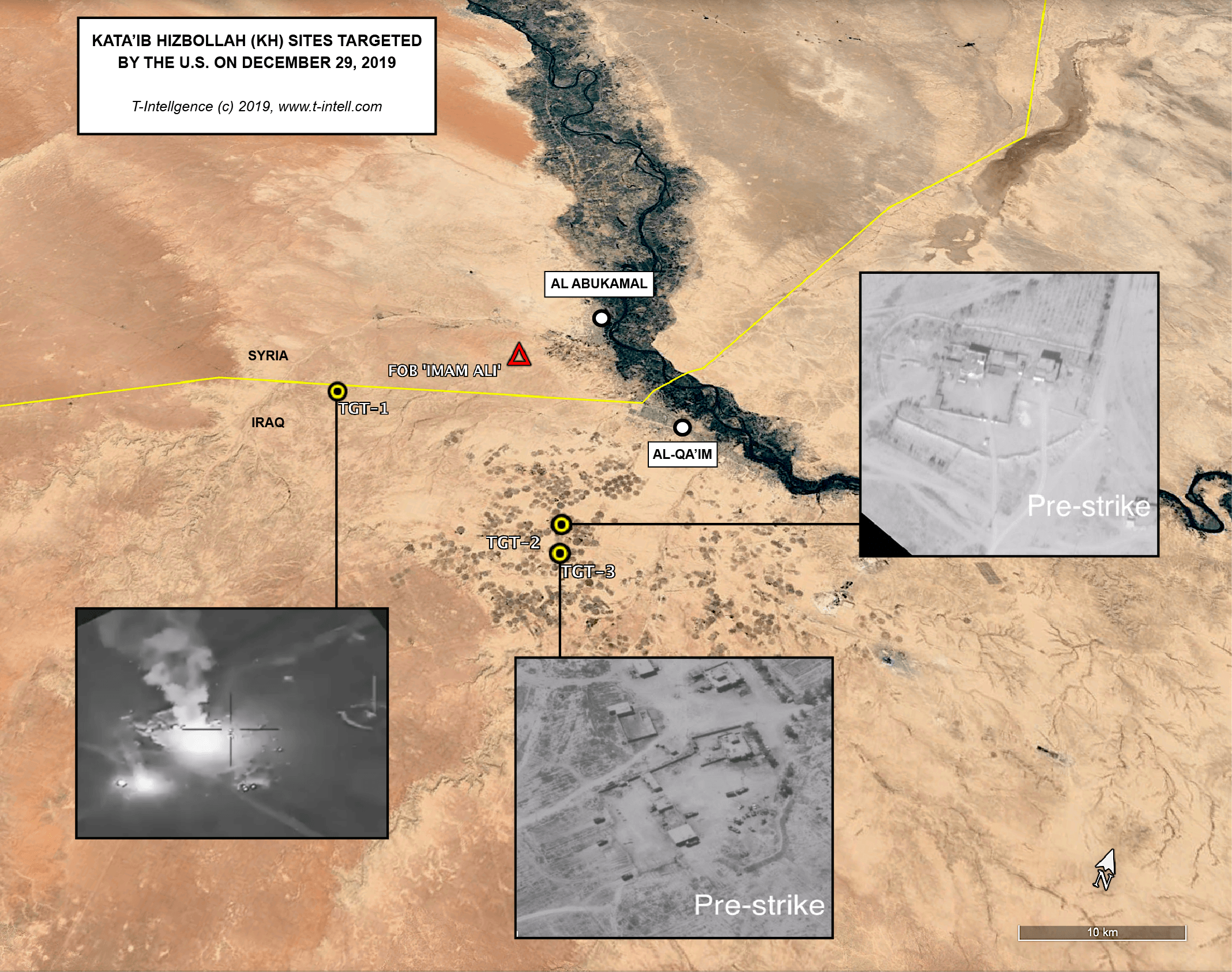

(b) Overall, it is unlikely that the Trump administration will venture into regime change operations. Any hypothetical U.S.-led military engagement against the Venezuelan regime will likely be limited, as seen in the previous strikes against the Syrian government’s Shayrat airfield and chemical weapons sites. The most likely of the unlikely military engagements will be an air interdiction operation, aimed at reducing the government’s capability of inflicting mass-casualties on opposition targets. Also known as a No-Fly Zone (NFZ), the U.S. could ground the Venezuelan Air Force’s (VAF) aircrafts and suppress its air defences.

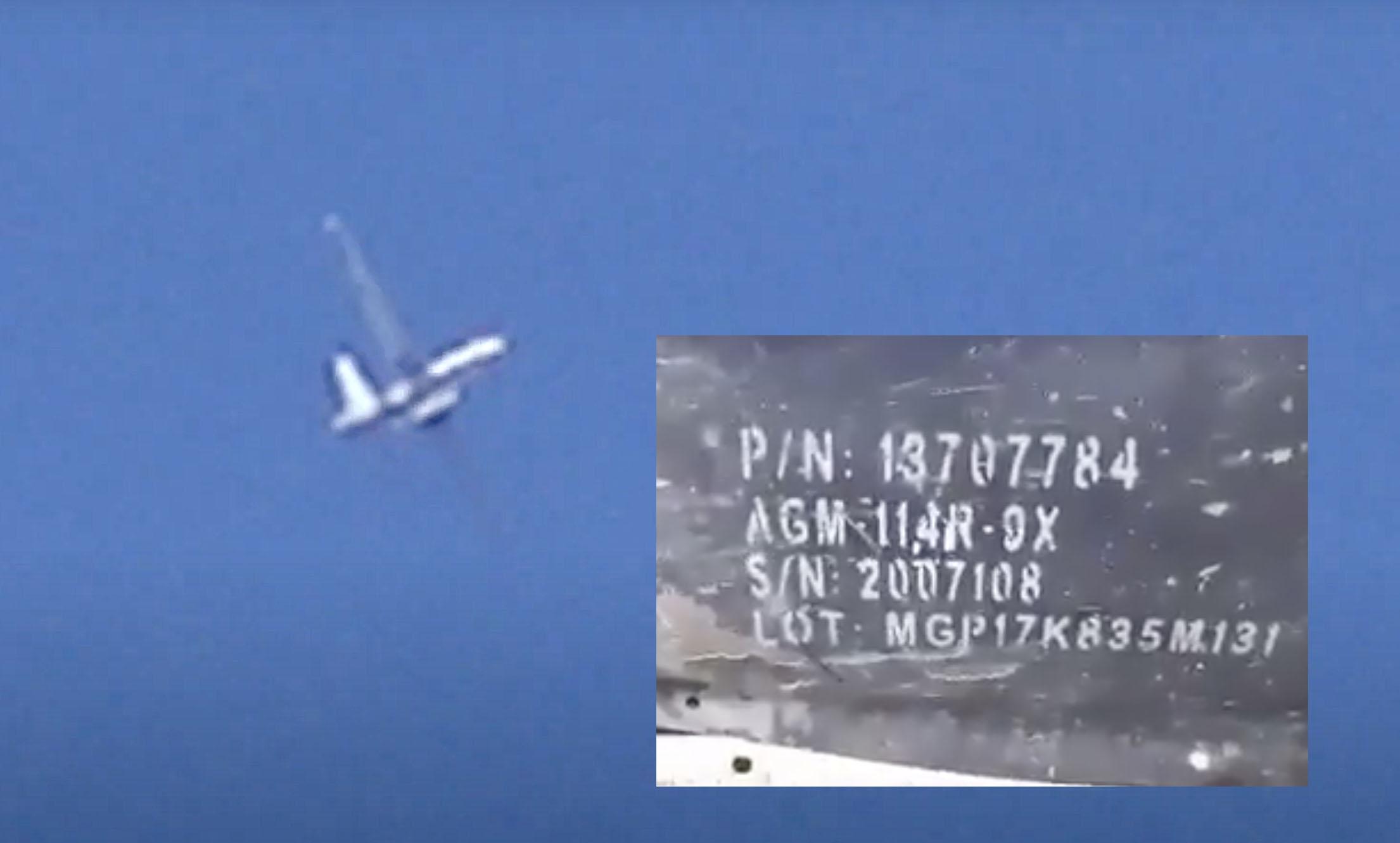

(c) The United States has never conducted air interdiction missions in an environment contested by fourth generation aircraft and advanced anti-access surface-to-air missile (SAMs) systems such as Venezuela’s Su-30MK2 and S-300VM SAM system respectively. While sidelined in the last NFZ operation in Libya, the F-22A could however take a control role in such a hypothetical engagement.

The Su-30MK2/ Flanker-C Threat

1. While overall modest, the Venezuelan Air Force (VAF) is regionally superior in terms of aircraft and air defense systems. The VAF’s combat aircraft inventory is particularly interesting, as it sports a combination of 20 mostly “canabilized” and unoperational F-16 Fighting Falcons A/B and 23 fourth generation “plus” Russian Sukhoi Su-30MK2 (NATO Reporting name: Flanker-C).

2. Like the Su-33 (Flanker-D) and Su-35 (Flanker-E), the Su-30MK2 Flanker-C is an evolution of the Su-27 family (Flanker-A/B). This variant was designed in particular to outmatch its American counterpart, the F-15 Eagle, in air superiority battles. While the United States stopped investing in the F-15 family (except for export) when transitioning to the F-22A Raptor as the nation’s air superiority aircraft, the Russians continued to enhance the Flanker-family. The limited number of Flanker-C aircraft in the VAF’s inventory will likely be a strong incentive for the U.S. to deploy the F-22A for air-to-air combat, at least in addition to the more equal F-15 or F-18 aircraft.

3. As in all fighter jet comparisons, there is much controversy about the balance of power between the F-22A and Russia’s Flanker-family. While the F-22A very low-observable (VLO) classified radar-cross section (RCS), supercruise speed and standoff sensors render it superior, some estimates claim that the Flanker-C/D/E is closing the gap in terms of avionics, maneuverability and armament.

4. In a hypothetical air combat maneuver (ACM) or dogfight, the F-22A Raptor could detect the Flanker-C using the APG-77, a long-range (160 to 250 km) low-probability of intercept radar, and engage it with standoff munition from beyond-visual range (BVR) without being detected. This is called the first look, first shot, first kill doctrine and its central to the F-22A engagement tactic.

5. The Flanker-C’s own passive-electronic scanner array (PESA) radar, called N-001 VEP, was developed for the Flanker-A in the 1980s to outperform the USAF’s F-15E Strike Eagle’s onboard sensor. Even with upgrades, the Flanker-C’s detection capabilities are vastly inferior to fifth generation sensors and obsolete against VLO RCS foes. Currently, the only Russian-made radar that can pose a threat to the F-22 is the IRBIS-E, an active-electronic scanner array (AESA) developed for the Flanker-E. The IRBIS-E is capable of detecting normal airborne targets at a distance of 300 km. The F-22’s VLO RCS, while classified, is believed to be between 0.0001 and 0.0003 square meters, with the frontal aspect performing better. Within these parameters, it is estimated that the IRBIS-E could detect the F-22A at a distance of 50 to 90 km.

6. Should the F-22 be drawn into a small- or medium-range fight or acquire a horizontal ACM pattern, the Flanker-C becomes a challenging adversary. In visual range direct engagement, the F-22A major weakness is its smaller number of electronic warfare (EW) vulnerable air-to-air missiles that it can carry in comparison to the Flanker-C. However, the inclusion of the AIM-120 AMRAAM blocks C-D allows for a 120 to 160 km operational range with increased EW resilience. While the F-22’s VLO-nature mandates a limited and concealed payload, the jet can compensate the limited munnition number by participating in a combined strike force with the “missile truck” F-15 or other aircraft (tasked with targeting the VAF’s F-16s), even relaying targeting data via data link.

7. The VAF lacks BVR standoff munition equivalent to the AIM-120 AMRAAM block C/D as well as the training and combat experience of American and Russian pilots. Furthermore, such direct comparisons are ineffective when applied to real combat scenarios. In a NFZ operation, the F-22A Raptors will likely be supported by AWACS, Electronic Attack (EA) aircraft and naval assets. At the same time, the VAF will seek to draw the ACM in the engagement range of its SAM batteries. However, as the F-22As ACM tactics rely on standoff BVR combat, the air superiority jet will avoid medium-range fights at all costs and even disengage when necessary. In a 2017 joint aviation exercise, the F-22A exercised ACM against Malaysian Royal Air Force Su-30MKK (Flanker-G).

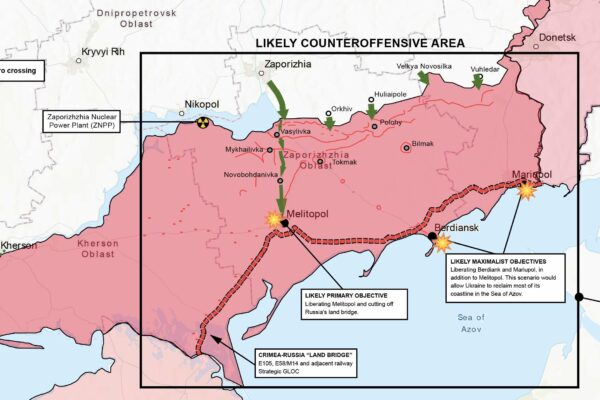

8. Besides ACM, a hypothetical U.S. NFZ over Venezuela would also involve massive ship- and air-launched cruise missile attacks on the VAF’s airfields and logistics (fuel storage, hangers, etc.). This would reduce the number of fighter jets that the Venezuelans could get airborne in the first place. However, that would bring surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems into the equation.

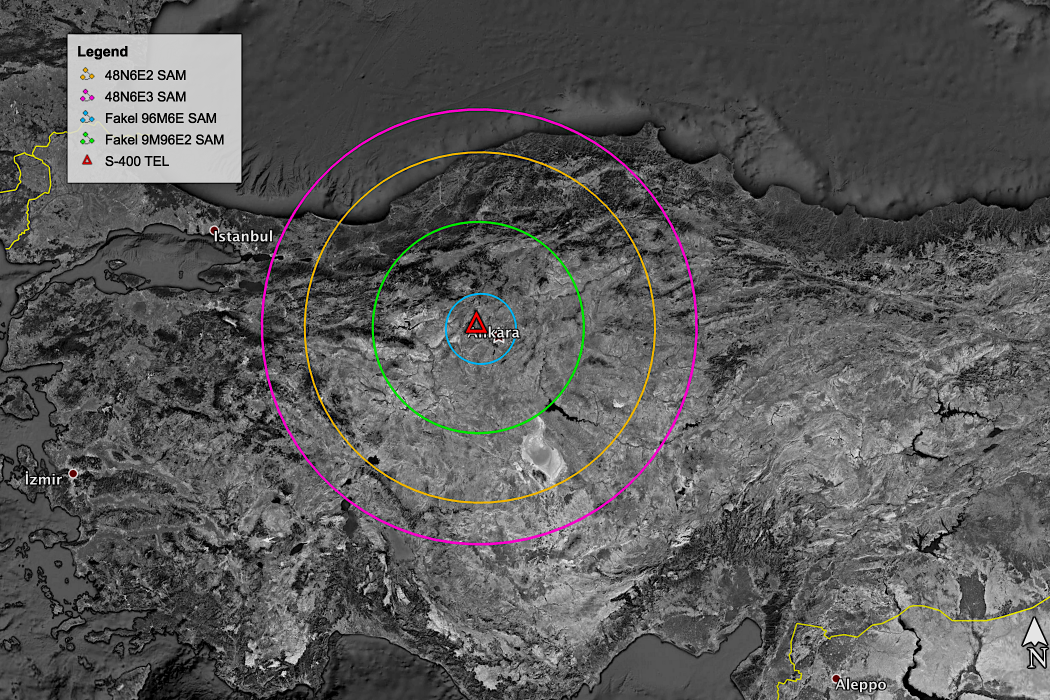

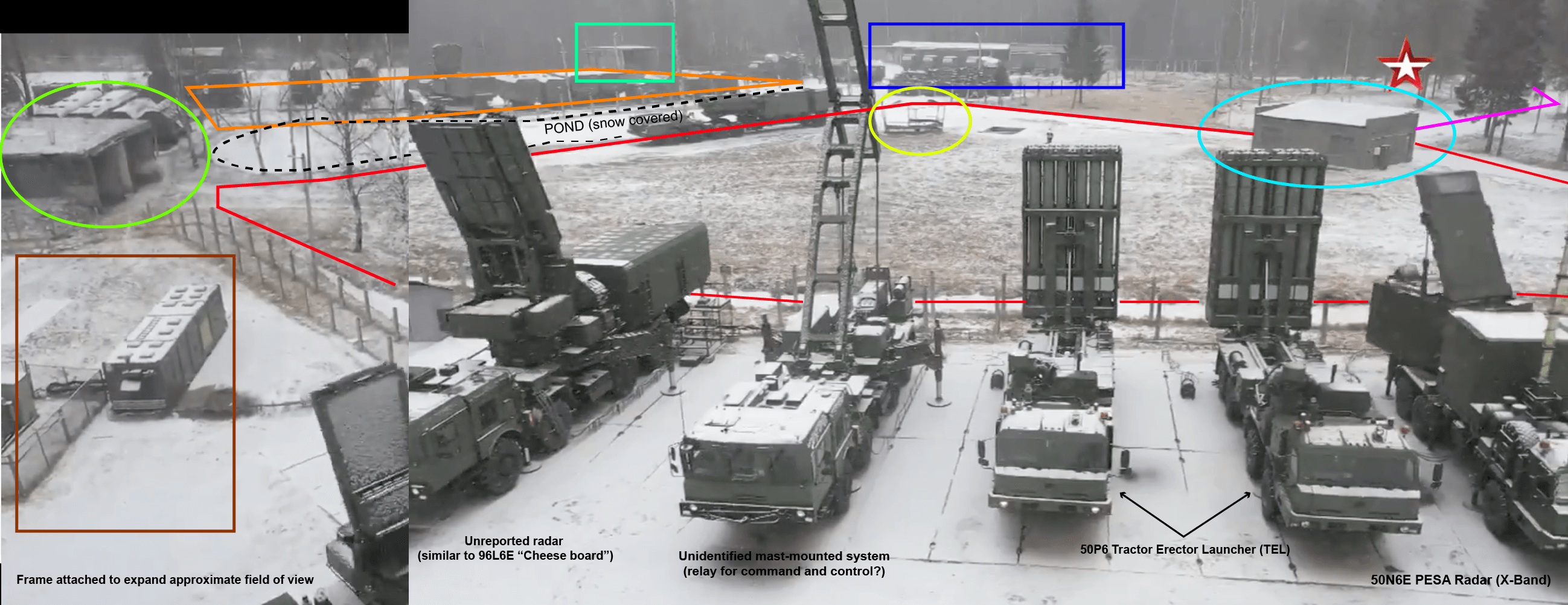

Confronting the S-300VM/ SA-23?

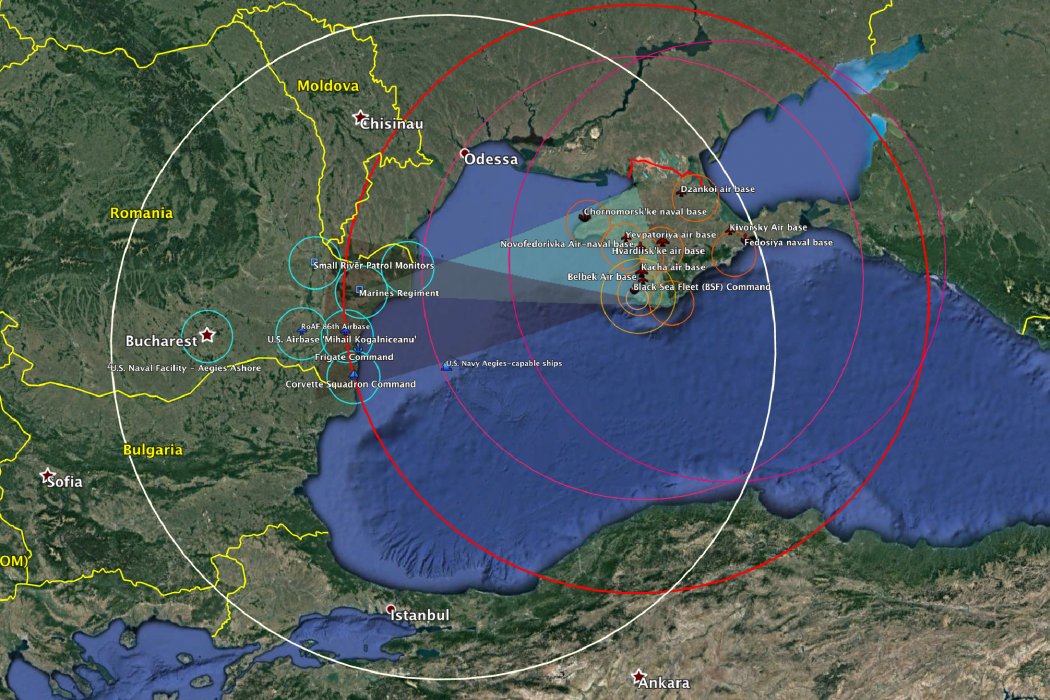

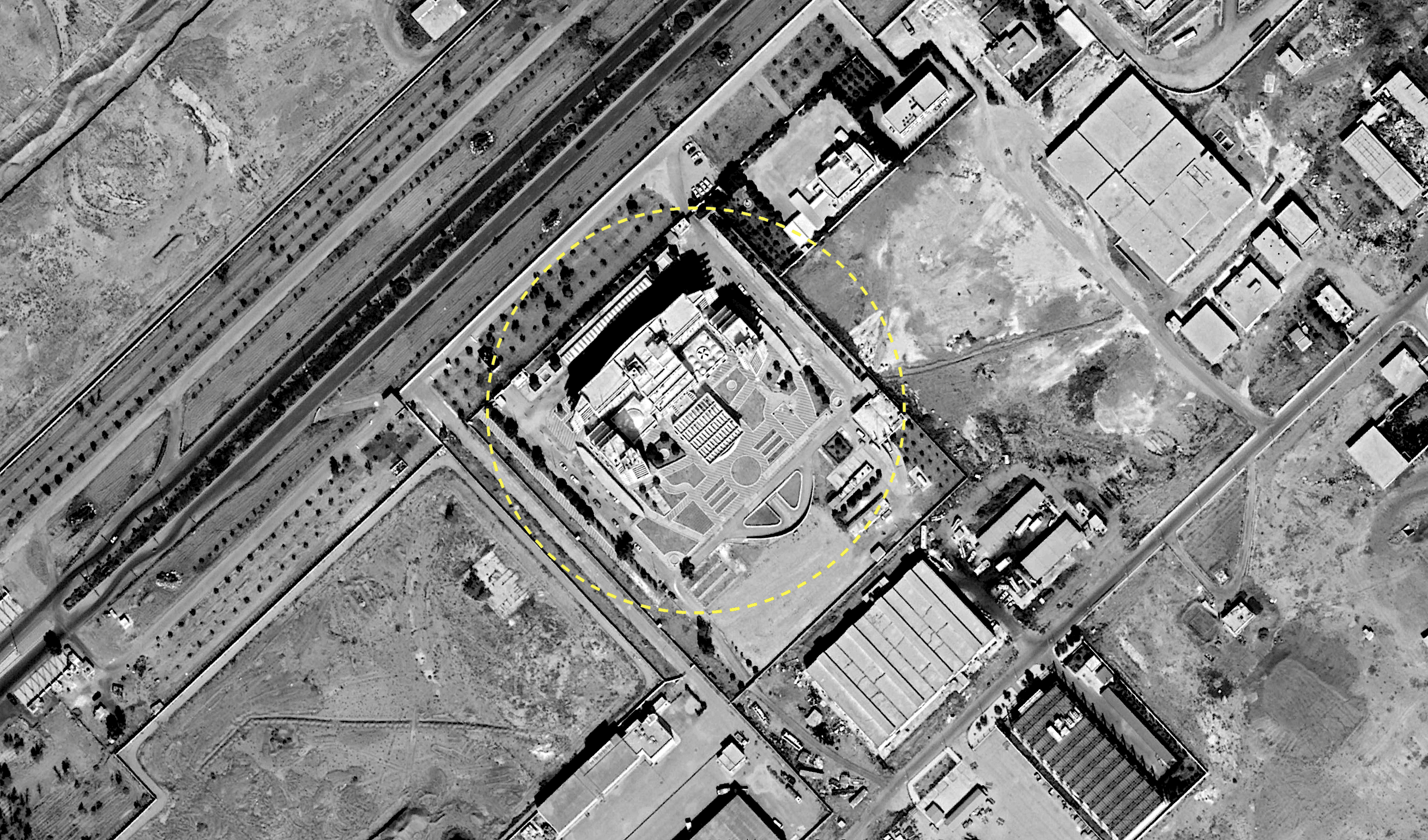

9. Venezuela has the most the most robust air defense in the region. The Comprehensive Aerospace Defense Command (Commando de Defense Aerospatial Integral/ CODAI) tasked with defending Venezuela’s airspace, is directly subordinated to the Operational Strategic Command of the Ministry of Defense. The mentionable assets operated by CODAI are three long-range S-300VM (SA-23 Gladiator) SAM systems used for area air defense (AAD) and several mid-range Buk M-2 (SA-17 Grizzly) for point air defense (PAD). Most assets are deployed to provide overlapping and saturated coverage over key governmental and military sites in Caracas.

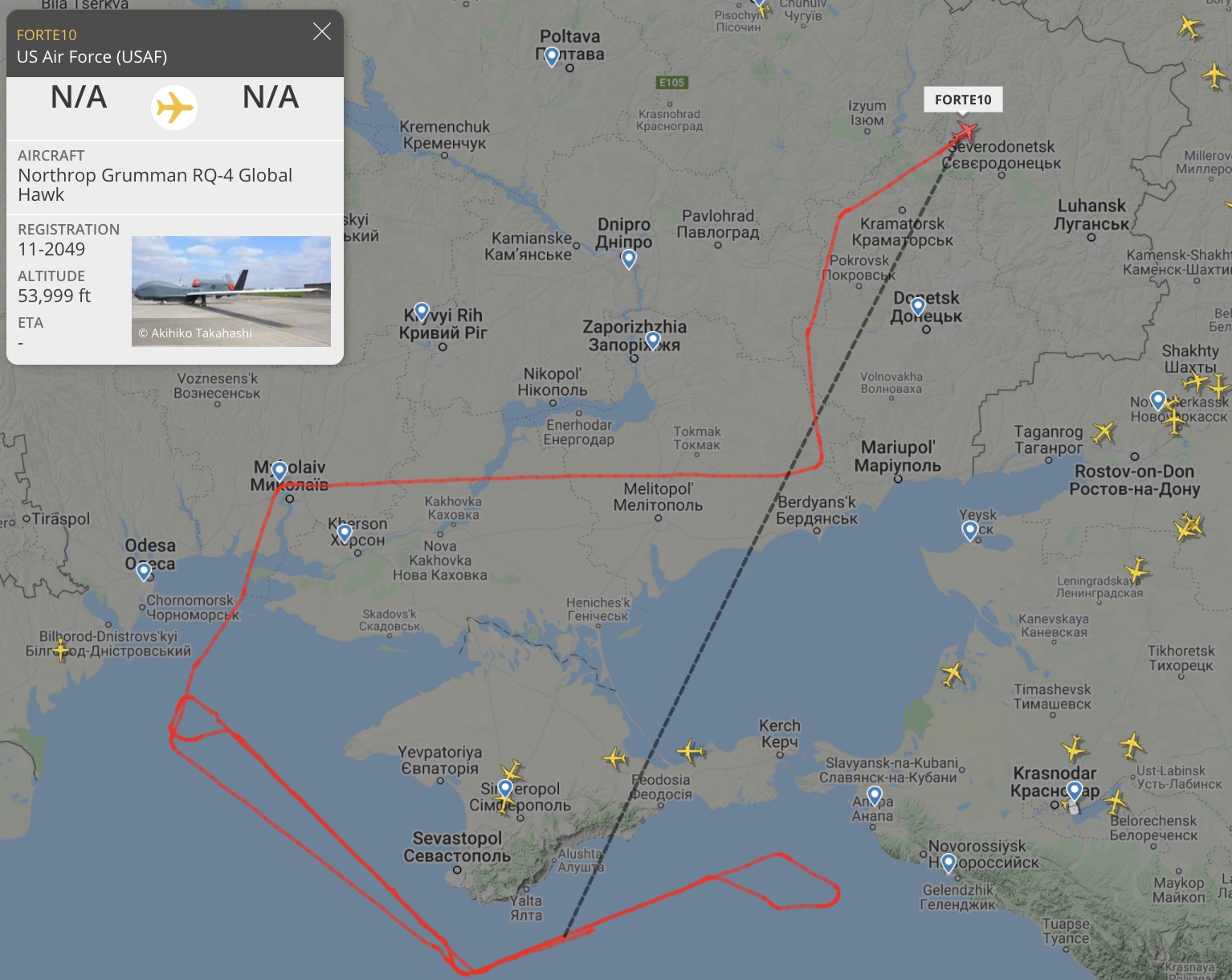

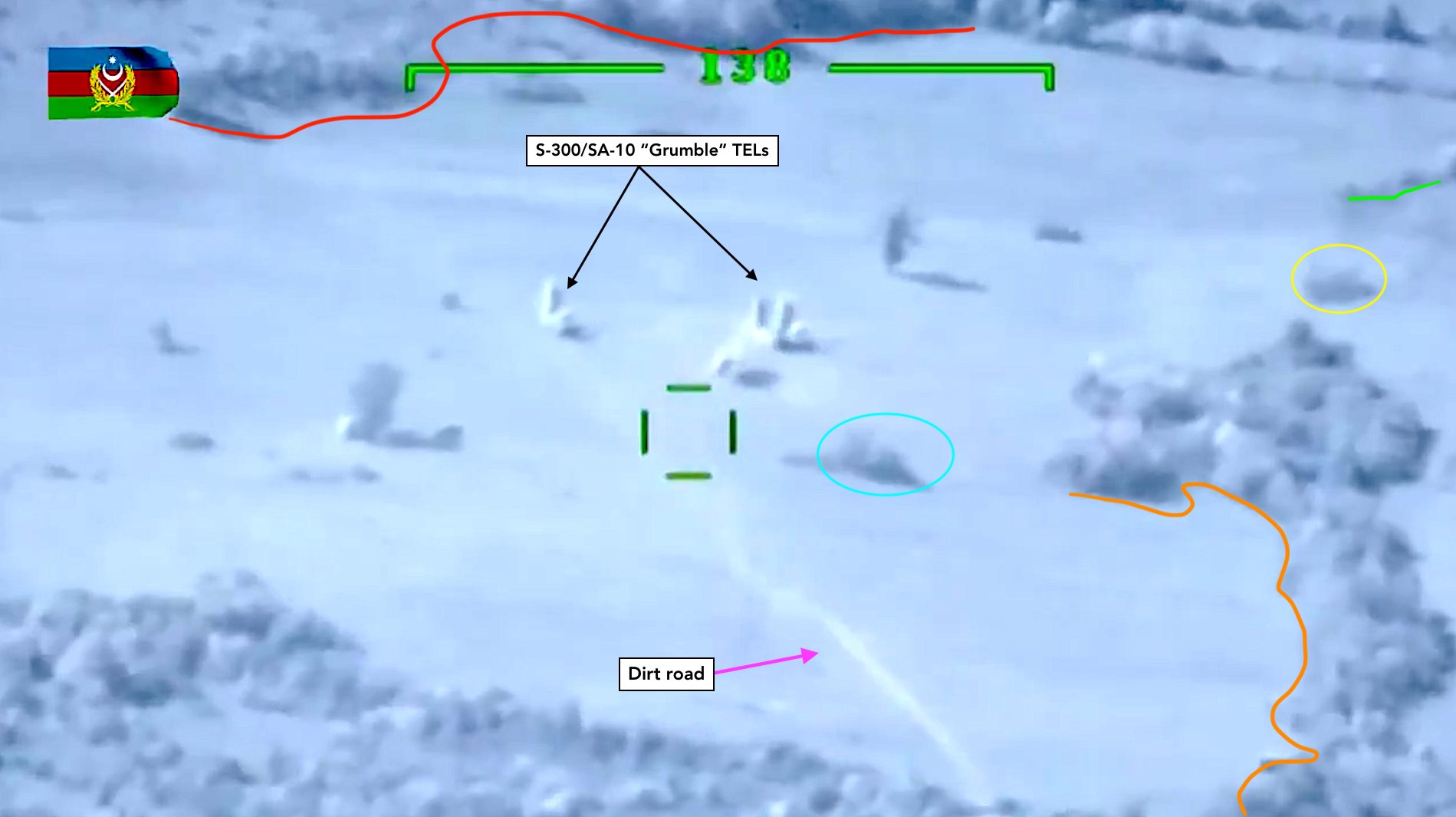

10. The SA-23 is a capable anti-access asset, threatening ballistic missiles, fighter jets, heavy lifters and even unmanned aerial vehicles. U.S. AWACS, AEW and ISR platforms would be at the highest risk, even at the SAM’s 200-350 km range edge. The U.S. operates its own S-300, acquired in the 1990s from Belarus that it uses for defense research and development purposes and for pilots to test ways to defeat the system. Likewise, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) has likely acquired critical intelligence on how the system functions from allied S-300 operators such as Slovakia, Greece and Bulgaria, and Ukraine.

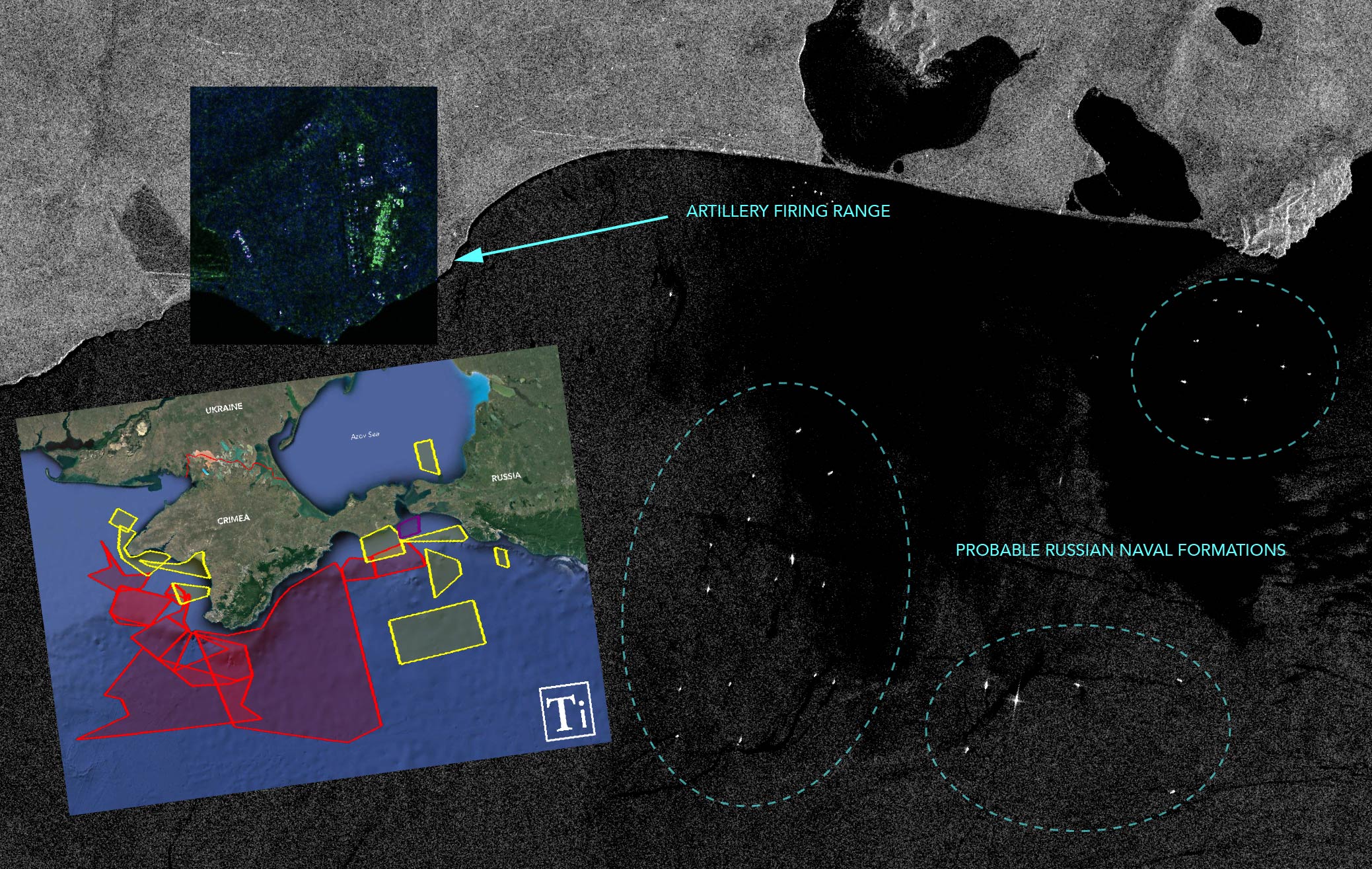

11. Theoretically, a F-22A or F-35B can enter a S-300 denied airspace and strike the battery or guide external-launched standoff and loitering munition to the target. Such a penetration would require a terrain hugging flight path, massive electronic attack support from airborne platforms, such as the E/A-8 Growlers, and a small payload for the F-22/F-35.

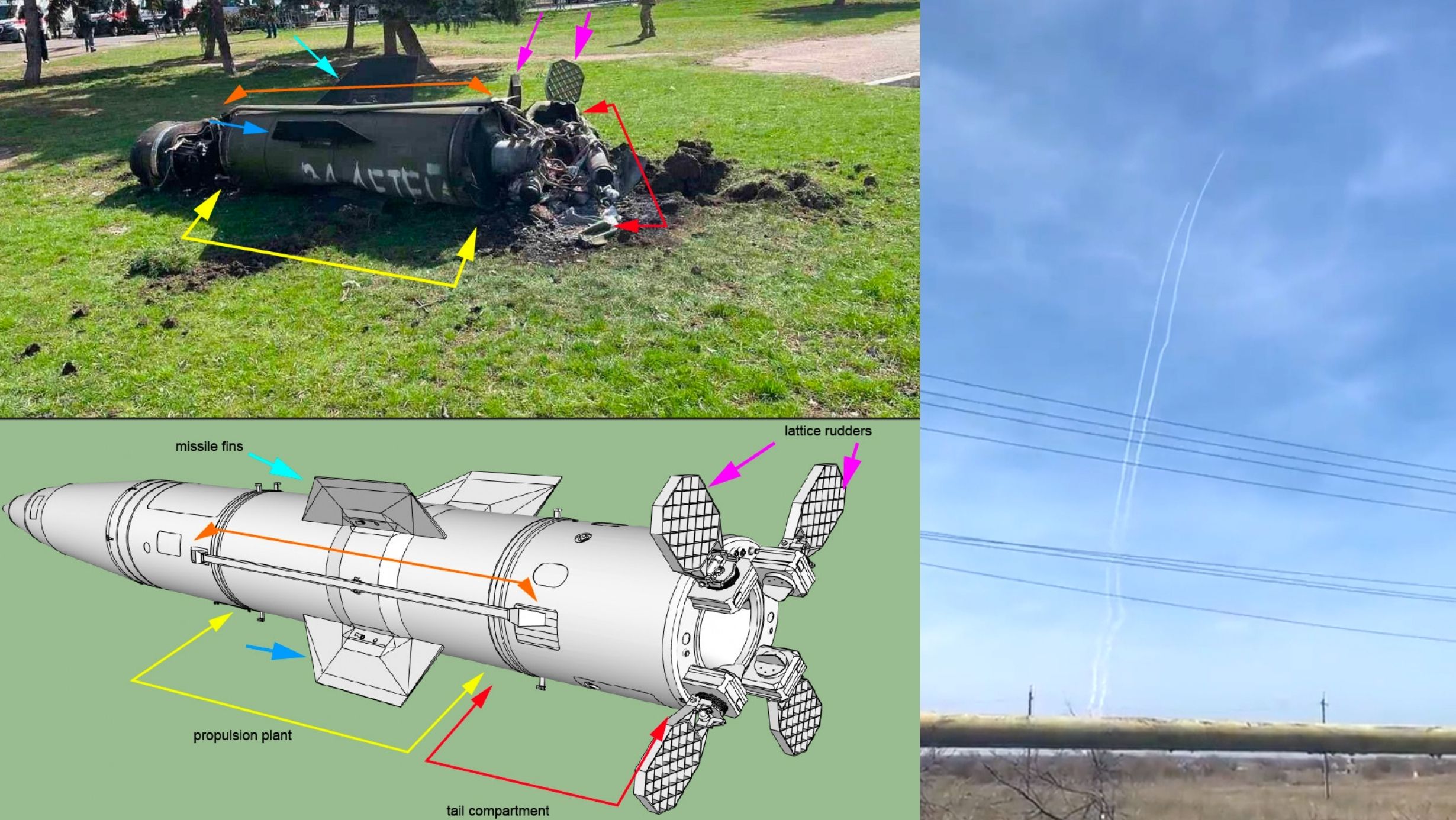

12. The VAF uses the highly-mobile self-propelled Buk M-2/SA-17 SAM to counter air-breathing threats. As the SA-23’s long-range high-altitude coverage would push aircraft to fly low and use terrain to hide from radars, the Buk M-2 would have a greater opportunity to intercept missile attacks. Some analysts estimate that the SA-17 is performing better than the Pantsir S-1 (SA-20 Greyhound).

13. CODAI also operates SA-2 and SA-3 SAMs. However, NATO does not consider these systems as anti-access capabilities, given how inefficient they are in the face of current technology. On the other hand, CODAI is equipped with approximately 5,000 Russian-made Igla-S (SA-24) man-portable air defense missile systems (MANPADS). The shoulder-fired SAM is quickly deployable, difficult to track and poses a great threat to low altitude penetrations.

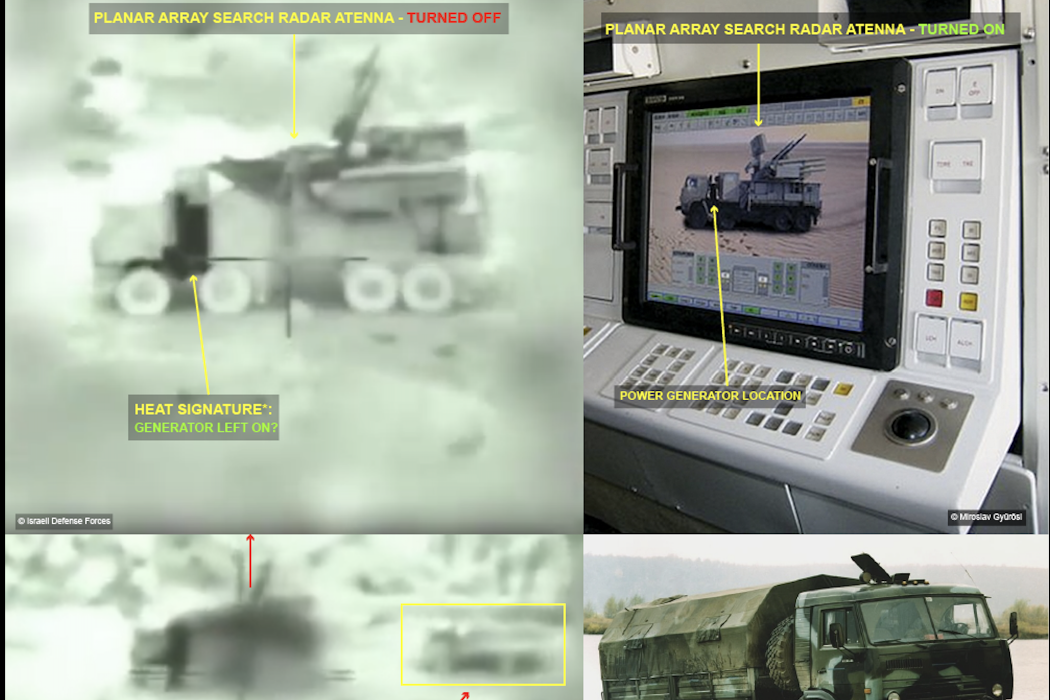

14. Should the unlikely NFZ operation also contain a suppression/ destruction of enemy air defense (S/DEAD) element, the U.S. would likely conduct multi-platform air-naval saturation strikes, which would overwhelm the CODAI’s SAMs and subsequent radars. As seen in recent SEAD engagements, air defense unit cannot maintain a 24/7 high readiness. SAM systems can be caught off guard, the personnel can be unprepared or give in to psychological pressure. Overall, Venezuela will not be able to protect its airspace if the United States takes out its Flanker-Cs. Follow-up S/DEAD sorties might not even be needed.

15. In past NFZ operations, adversaries regularly complied to the new operational environment after the “first day of war”. The defenders chose to ground their aircraft and switch the SAM radars off to increase survivability of their armed forces, when attacking forces were reported in the area. In other engagements, such as the air campaigns in Yugoslavia and Vietnam, defending SAM personnel caused tactical surprises. While we cannot estimate how a hypothetical NFZ operation in Venezuela will turn out, it would certainly be the most contested airspace that U.S. forces experienced in the past decades.

UPDATE 24.2.2018

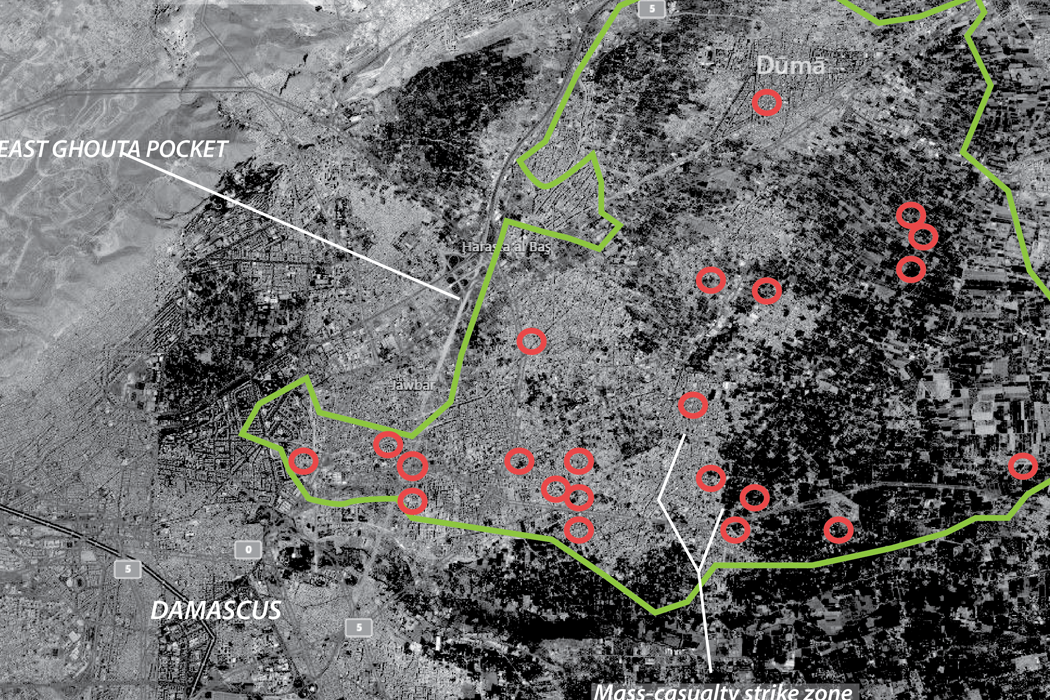

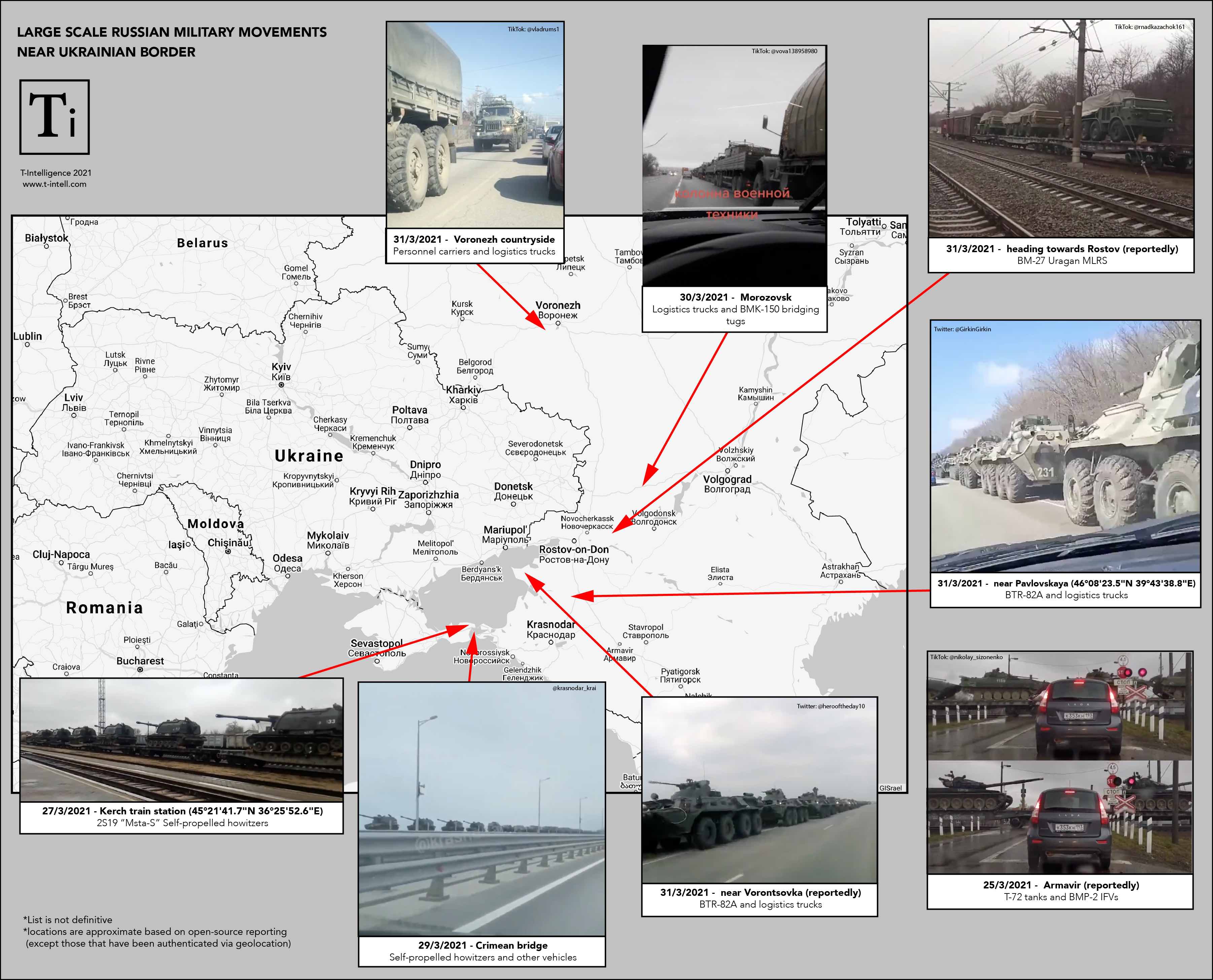

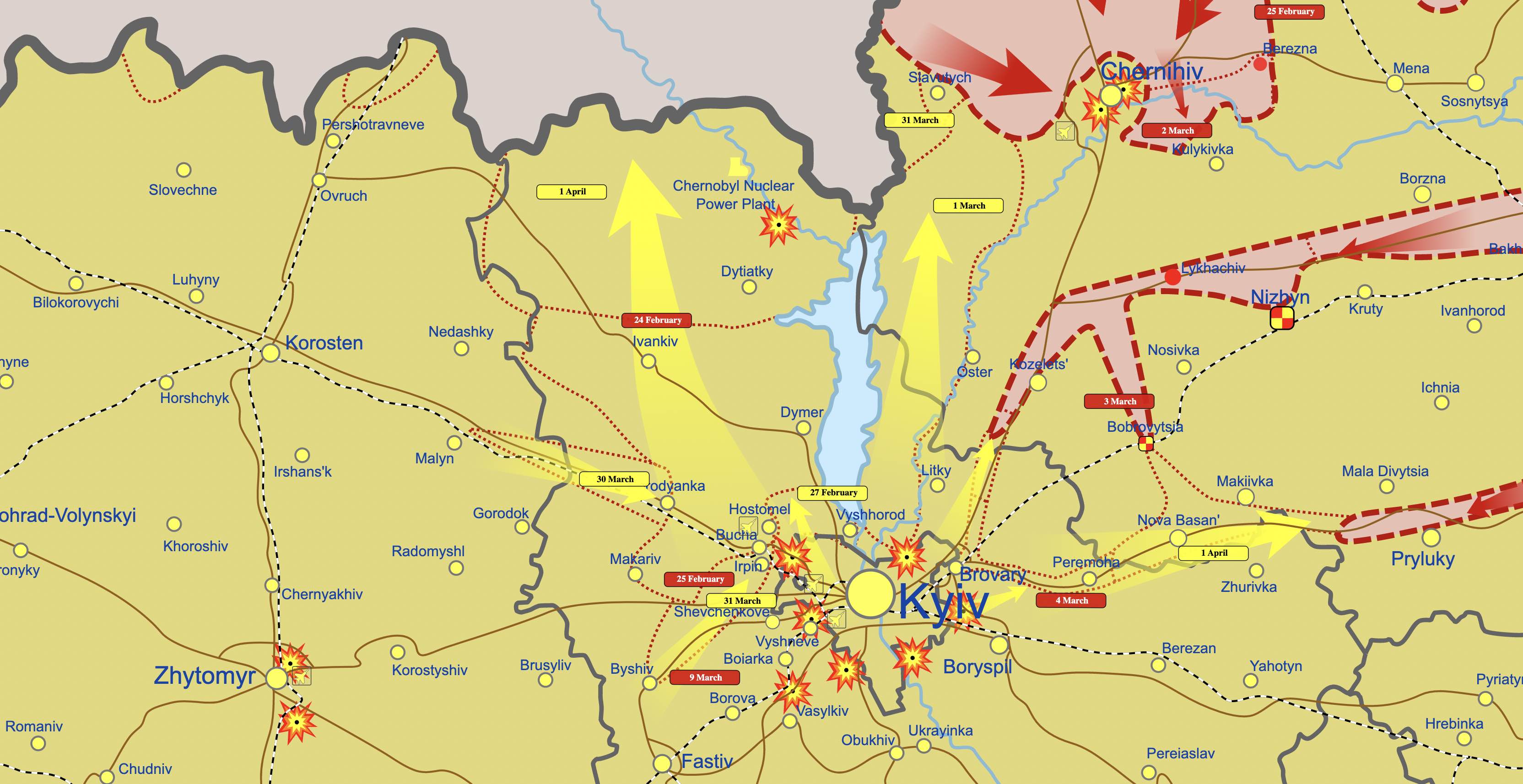

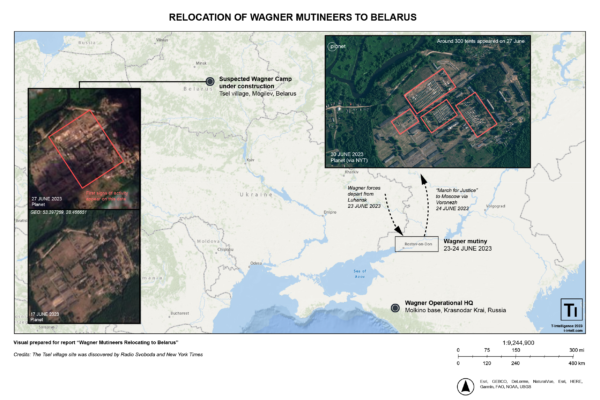

16. This analysis has been updated with an OSINT-based imagery intelligence map showcasing the known SA-23/S-300VM deployments at Manuel Rios air base (AB) and the Brazil-Guyana border. Several Flankers have been forward deployed from Luise del Valle Garcia AB (near Barcelona) to Caracas. Not all SA-23 tractor erector launchers (TELs) are concentrated in the pint-pointed positions. While impossible to verify at this point, a third SA-23 system is rumored to be deployed in an AB north of Caracas.

VAF’s ABs and SA-23 sites via T-Intelligence

By HARM

Editing by Gecko

This analysis is neither news nor a forecast, but a purely hypothetical assessment.

VAF’s official name is the Venezuelan National Bolivarian Military Aviation (VNBMA).

VAF placed an order for 12 more Su-30MK2 from Russia, rising the overall inventory number to 35, however a delivery or initial operational capability date has not been estimated or announced.

If you like our content, please consider supporting us with a coffee: buymeacoff.ee/ur9UYj038

Founder of T-Intelligence. OSINT analyst & instructor, with experience in defense intelligence (private sector), armed conflicts, and geopolitical flashpoints.

![Pride of Belarus: Baranovichi 61st Fighter Air Base [GEOINT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/cover_article.jpg)

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 2]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TelSalman24.2.2018_optimized.png)

![This is How Iran Bombed Saudi Arabia [PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/map4cover-01-compressor.png)

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 1]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/KLZJan.62018copy_optimized.png)