Romania is in discussions with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to purchase the Giurgiulesti International Free Port (IFP) which is located in the Republic of Moldova. Romania’s plan to acquire Giurgiulesti IFP was first disclosed by Romanian Prime Minister Marcel Ciolacu during a Digi24 interview on 27SEP23 PM Ciolacu has stated that […]

Archive for the

‘Euro-Atlantic’ Category

The Arctic Circle is at the forefront of international geopolitical competition for shorter shipping routes, untapped oil & gas reserves, rare earth element & critical mineral deposits, and icebreaker shipbuilding and services. Unlock this free Executive Report and gain intelligence on: the global maritime shortcut offered by Arctic routes, including the Northern Sea Route, the […]

28 February 2024

Arctic Circle, Arctic Policy, Arctic shipping, China, Finland, Greenland, High North, Icebreaking, Intelligence Insights, Norway, Oil & Gas, Rare Earth Elements, russia, Sweden, United States

Arctic Rush, China, Critical Minerals, Geopolitical Risk, GIUK Gap, Greenland, Investments, Mining, Norway, Russia, Shipping, Sweden, United States

The Solomon Islands is in the early stages of state capture by China. With its growing geopolitical influence in the Solomons, China is expanding the Belt & Road Initiative into the South Pacific, an area of strategic importance for the Australia, United Kingdom, and United States (AUKUS) alliance. Unlock this free Executive Report and gain […]

Romania issued a tender for short-range air defense/very-short-range air defense (SHORAD/VHSORAD) on 17 November 2023. The contract, valued at around $1.908 billion, is anticipated to attract bidders from the United States, Europe, Israel, and South Korea. While years in planning, Romania’s SHORAD/VSHORAD program has likely been accelerated by the war next door in Ukraine. Mobile […]

24 November 2023

Chiron, defense procurment, Diehl Defence, Hanwha, IRIS-T, Kongsberg, LigNex1, MBDA, Mistral 3, NASAMS, Pegasus, Rafale, Romania, Romtehnica SA, RTX, Saab, SHORAD, Spyder, StarStreak, Thales Air Defence UK, VL Mica, VSHORAD

The Taurus air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) remains a coveted asset for Ukraine, offering unique bridge-busting capabilities that Storm Shadow/SCALP EG and ATAMCS lack. However, Taurus’ strength is also its weakness, as Berlin fears the missile would be used to destroy the Kerch Bridge and escalate the conflict. Despite some claims, Taurus production capacity is not […]

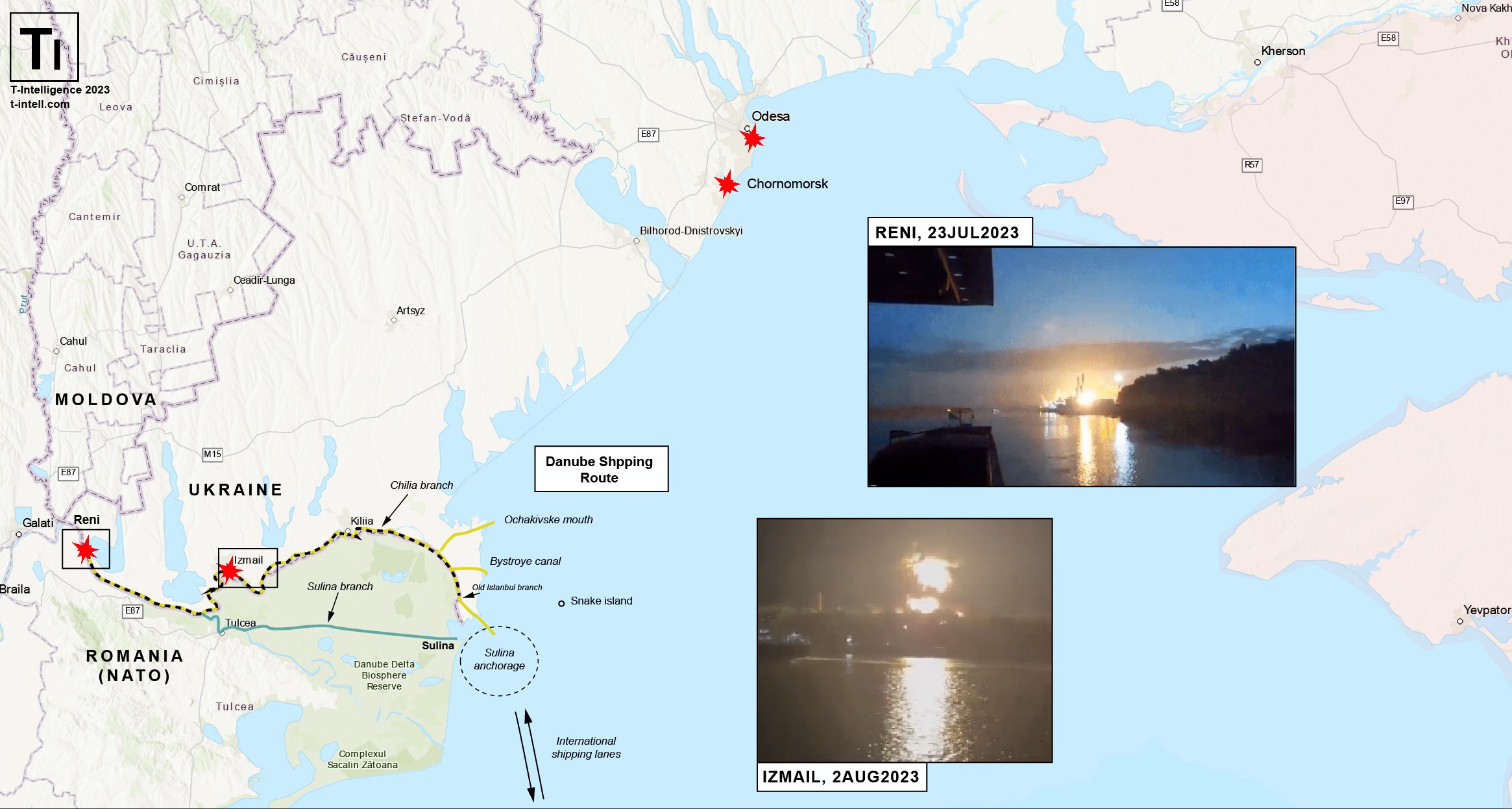

KEY JUDGEMENTS Russia’s missile and drone attacks against Reni and Izmail marked the first strikes on Ukraine’s Danube ports since the full-scale invasion began on 24 February 2022. The attacks are part of a new Russian campaign to degrade Ukraine’s ability to export agricultural goods and destroy grain stocks. They also seek to deter merchant […]

Snake Island, or Serpents Island (Ostriv Zmiinyi in Ukrainian; Insula Serpilor in Romanian) is an islet off Ukraine’s southwestern coast and near the Danube Delta in the Black Sea. With a surface of 17 ha, the islet became a major flashpoint between the Ukrainian Operational Command-South and the Russian Navy, following the Russian seizure of […]

In the early hours of 24 February 2022, Russia commenced a series of pre-assault operations to soften Ukrainian defenses ahead of an all-out, multi-axis invasion, which is now in progress. This course of events was extensively threatcasted by the OSINT community weeks in advance, including us. Those familiar with our estimates from January 2022, see here, would […]

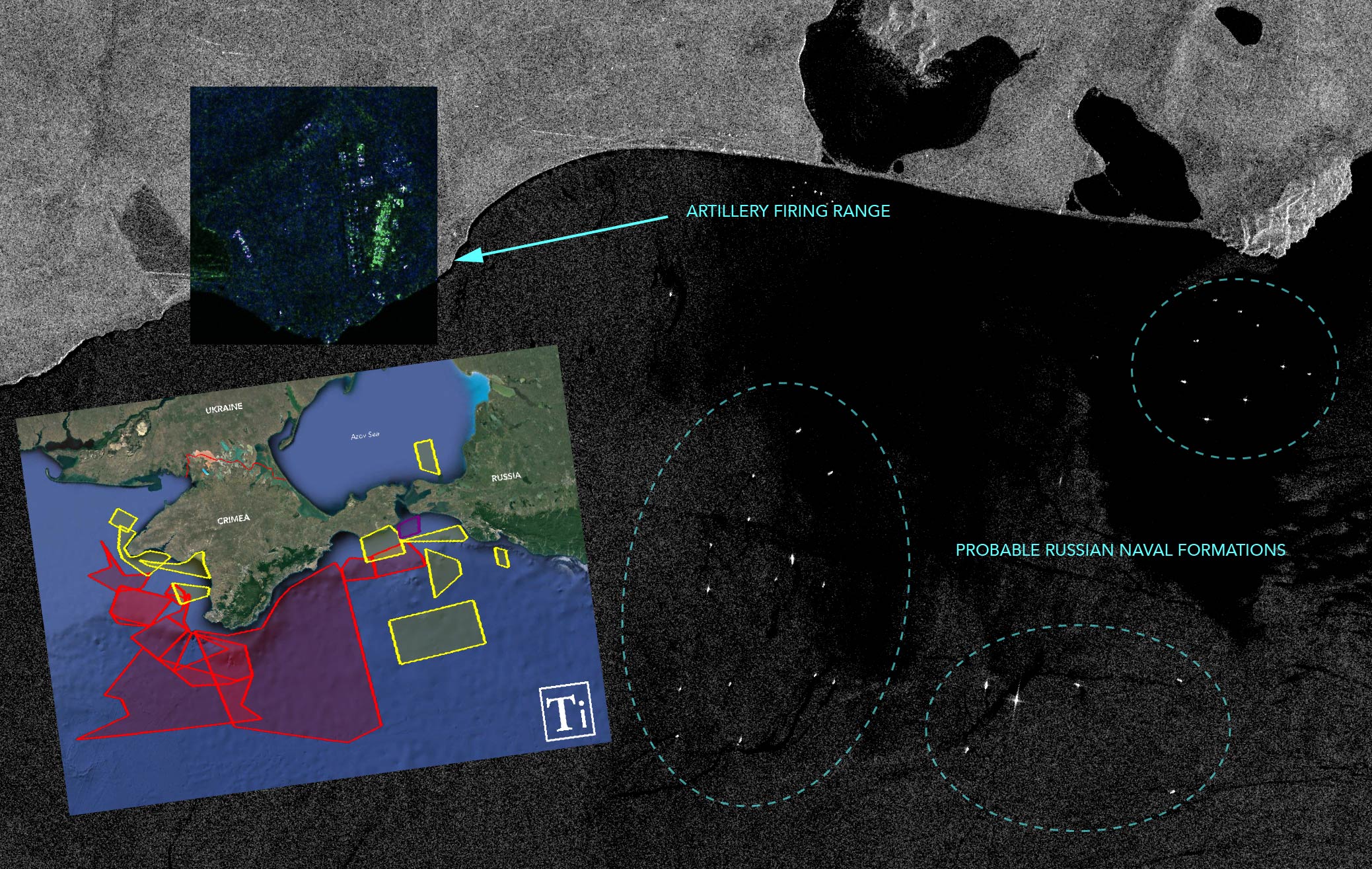

Last week, the Black Sea became the latest theatre upon which tensions flared between the United Kingdom and Russia. On June 23, the British Royal Navy’s Type-45 HMS Defender entered contested waters off the Crimean Peninsula while sailing from Odessa (Ukraine) to Batumi (Georgia). As expected, Russia reacted aggressively, sending fighter jets and warships to […]

5 July 2021

Black Sea, Crimea, HMS Defender, Royal Navy, russia, Sea Breeze 21, UK, Ukraine

Russia has concentrated warships from all fleets, except the Pacific fleet, in the Black Sea for joint drills. While not unprecedented, it is rare to see such a show of force. The cross-theater deployments and large-scale exercises bear the hallmarks of a maritime build-up intended to intimidate Ukraine and deter NATO activities in the Black […]

20 April 2021

Black Sea, Crimea, military exercise, NATO, OSINT, russia, Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine