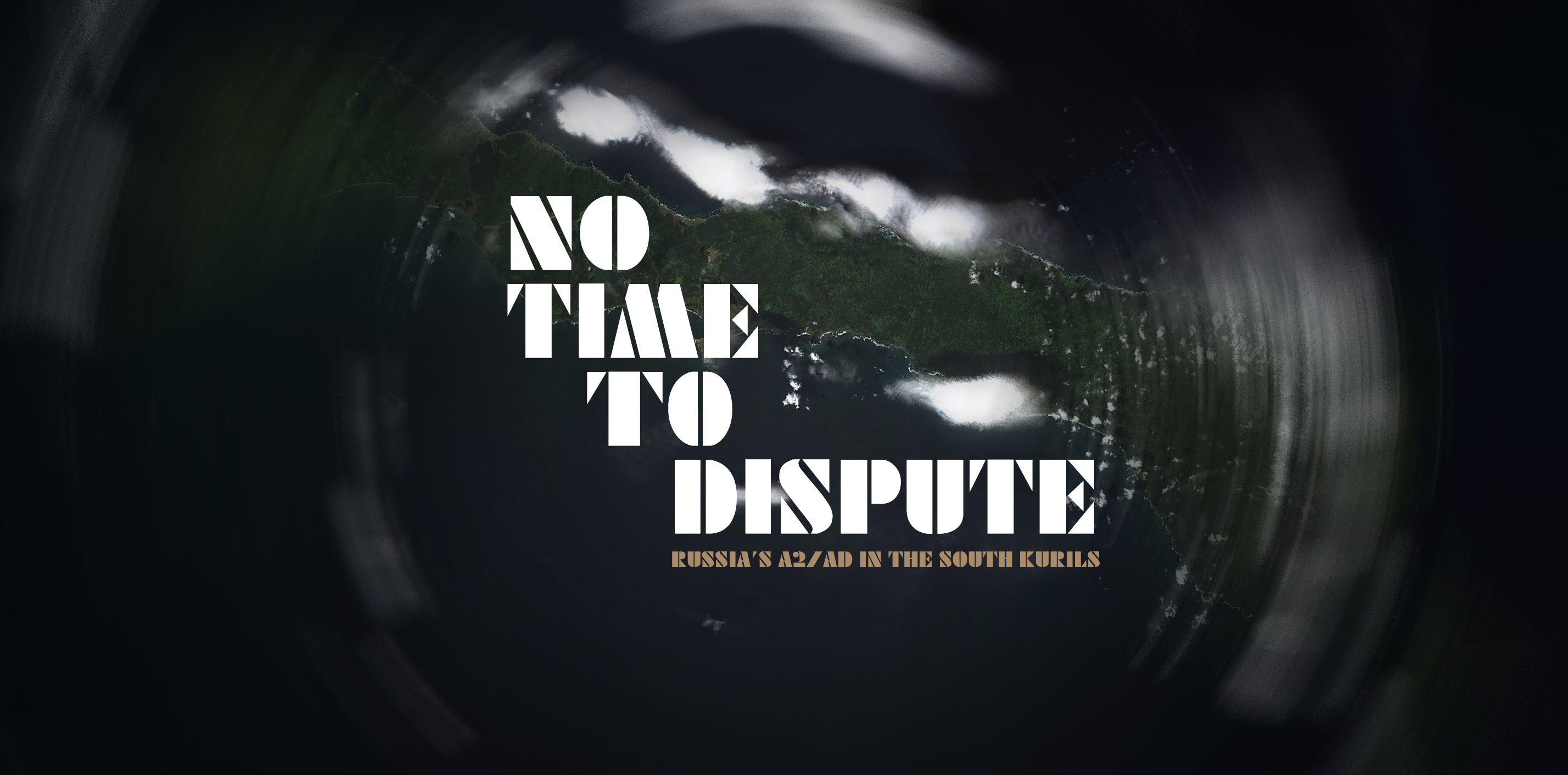

Remote and derelict, riddled with active volcanoes and disputed between Russia and Japan, the South Kurils make the perfect secret lair for any self-respecting evil genius. It’s no wonder the writers behind No Time to Die, the latest Bond film, chose the South Kurils as the setting for the film’s final act. While not directly […]

Posts Tagged

‘S-300’

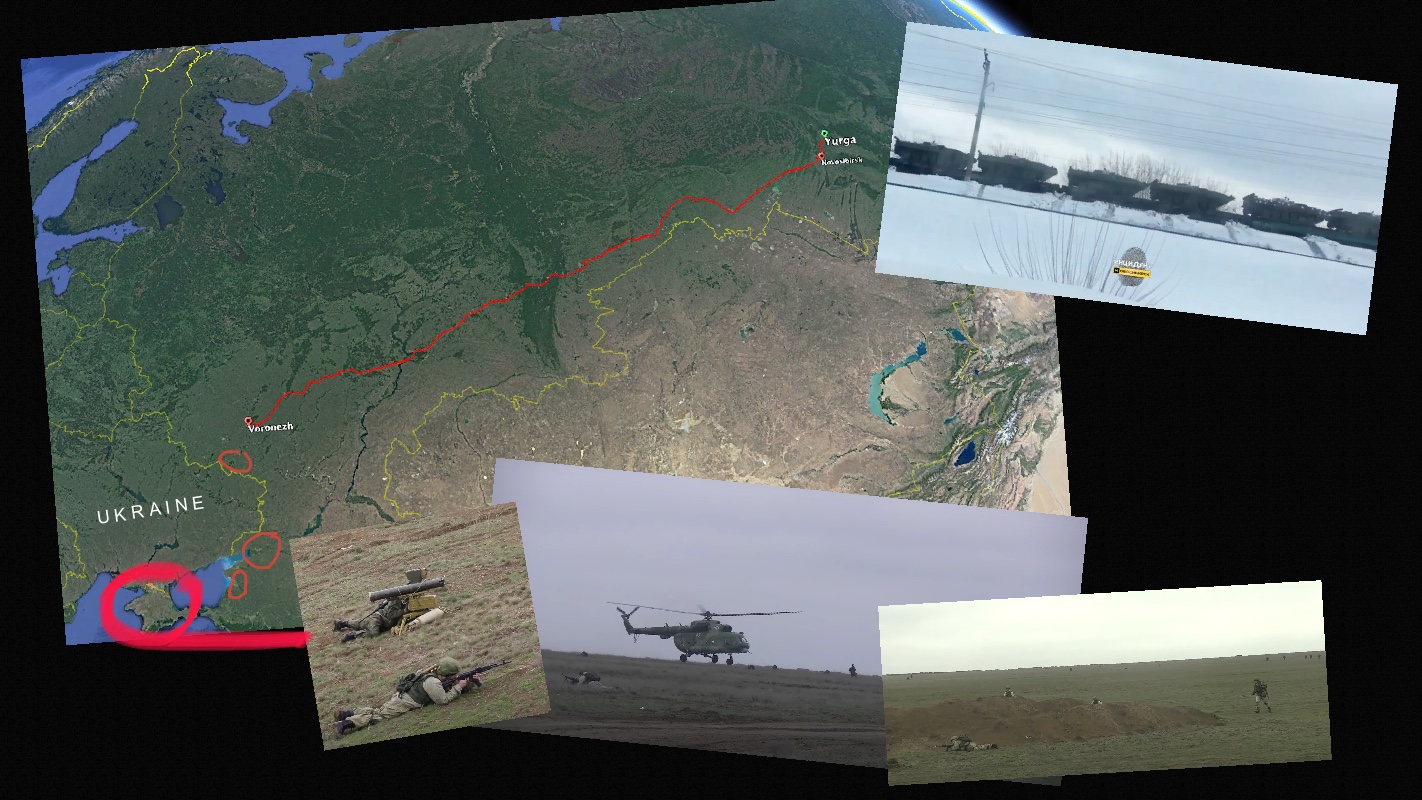

The Russian Federation’s military build-up near Ukraine is expanding, drawing forces from the Central Military District and escalating as thousands of snap exercises take place throughout the country. Social media users have continued to capture scores of rail flatbeds hauling main battle tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, rocket launchers, fuel trucks, and even air defenses. Sequel […]

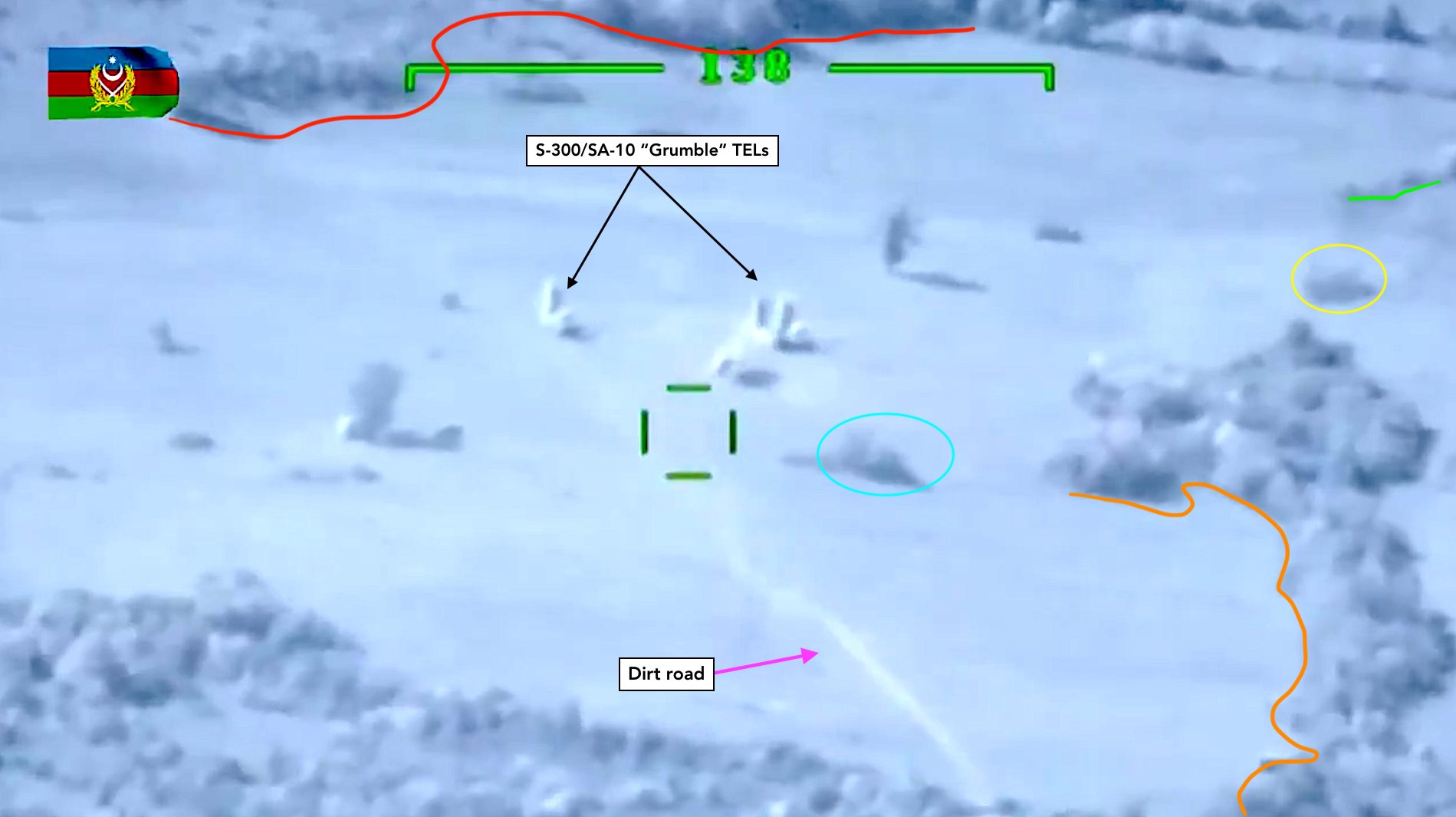

Azerbaijan has destroyed an Armenian S-300PS air defense system (AIFC/NATO: SA-10 “Grumble”) on 17 September 2020. The Azeri Ministry of Defense has released footage of an air strike on at least two entities consistent with S-300 tractor erector launchers (TELs). The blast radius indicates that Azerbaijan has used a heavy payload, possibly the Israeli ballistic […]

18 October 2020

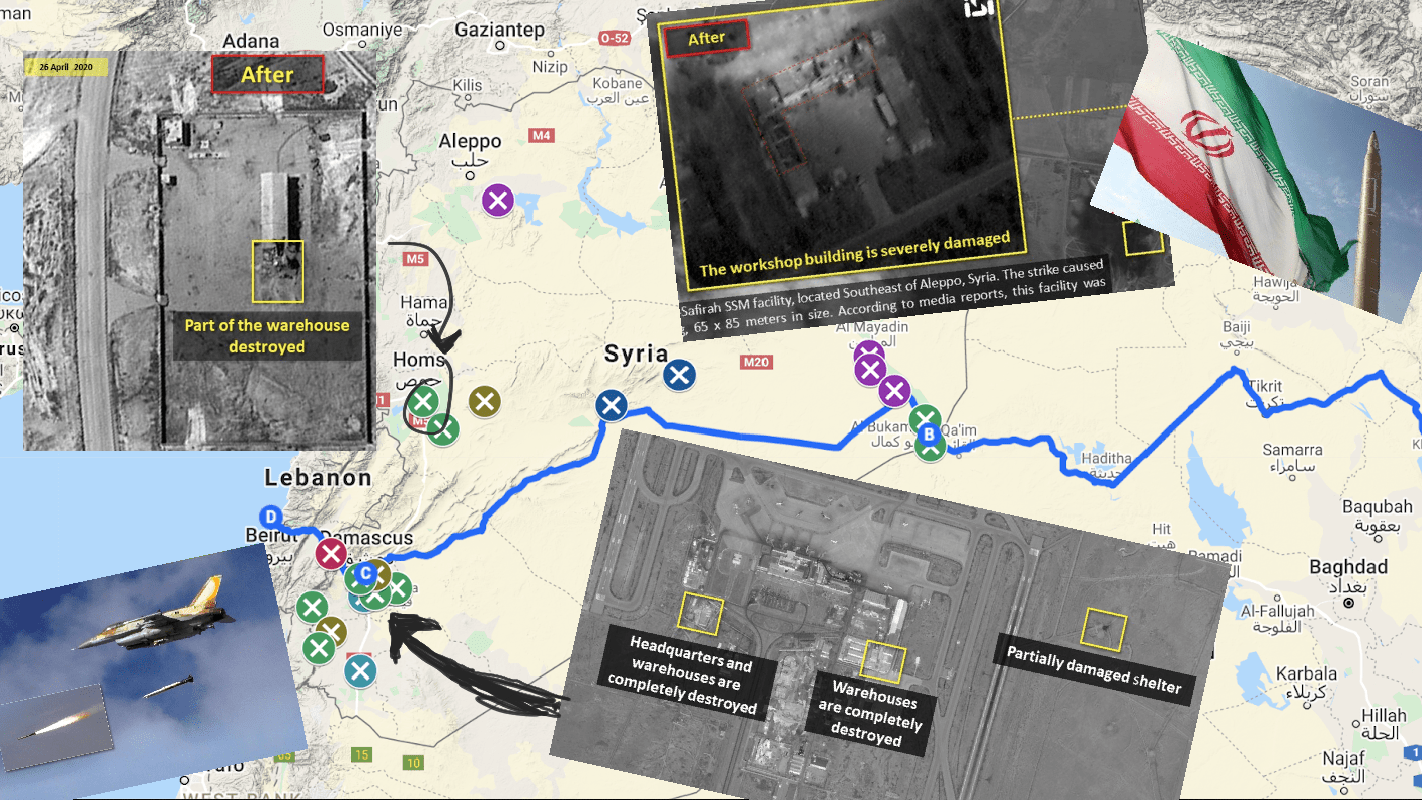

Over the past eight years, The Israeli Air Force (IAF) has conducted over 300 “unclaimed” airstrikes against the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) and its axis of transnational Shiite militias (the Iranian Threat Network/ITN) in Syria. Israel’s covert air campaign aims to avert an Iranian entrenchment in Syria and prevent the transfer of advanced weapons to […]

13 May 2020

Abu Kamal, airstrikes, al-Safirah, Damascus, Damascus International Airport, IAF, Iran, iraq, IRGC, Israel, Israeli Air Force, Lebanon, Mezzeh, PMU, russia, S-300, Soleimani, syria, Syrian Civil War

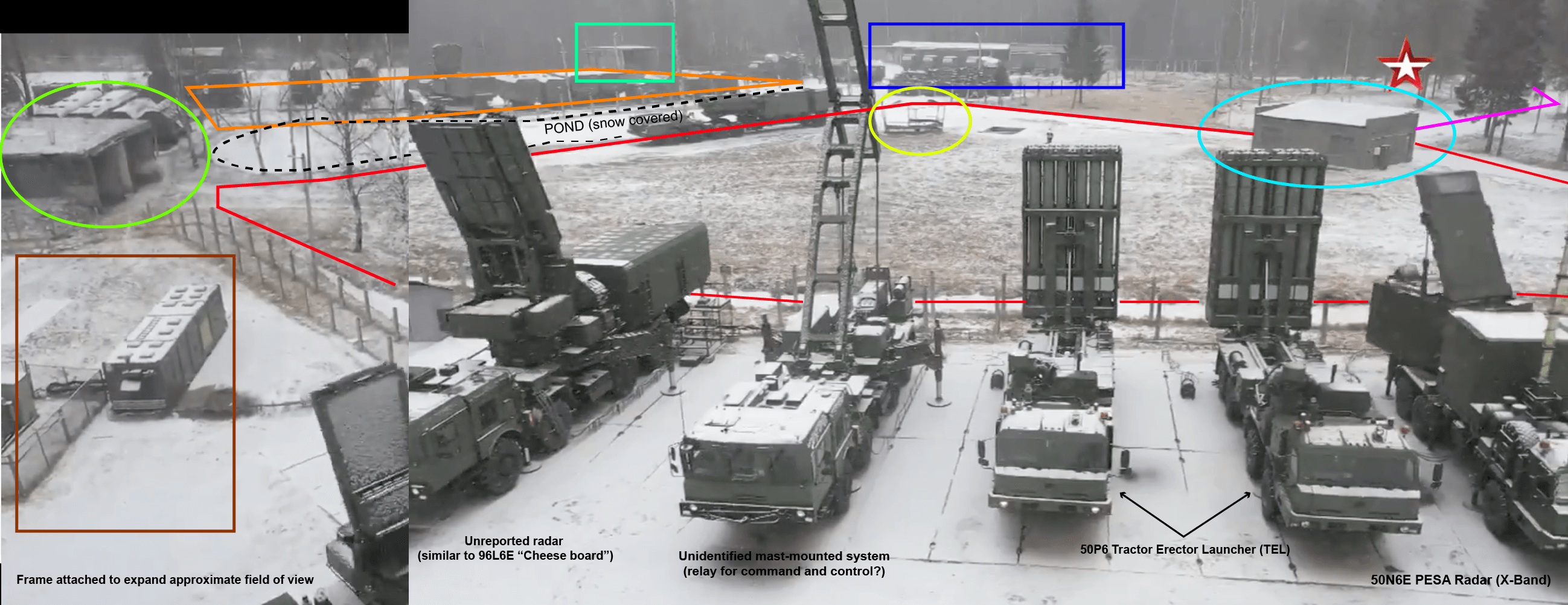

After long delays and setbacks, the S-350 “Vityaz ” SAM system finally entered service with the Russian Aerospace Forces (RuAF). The S-350’s first deployment is at the Gatchina training center in Leningrad oblast. We geolocated the exact deployment site shown in the “Zvezda TV” video to these GPS coordinates 59°32’44.4″N 29°56’46.1″E The RuAF is scheduled […]

28 February 2020

9m100, 9m96, air defense, Gatchina, russia, S-300, S-350, SAM system

Syria’s S-300PM2 surface-to-air missile (SAM) system (NATO reporting name: SA20-B Gargoyle) has likely achieved initial operational capability (IOC) or is about to achieve IOC by May/June 2019. In response to the Ilyushin-20 incident of September 2018, Russia transferred three battalion sets (with eight 5P85SE launchers each) of the SA-20B/S-300PM2 version (domestic/non-export) from its own inventory […]

18 March 2019

Ilushyin-20, Israeli Air Force, Latakia, russia, S-300, syria, Syrian Civil War

The following analysis is neither news nor a forecast, but a purely hypothetical assessment. (a) If the situation in Venezuela escalates and Russia moves forward with its plans to establish a strategic bomber presence in the Caribbeans, it is not out of the question that the United States will step up its opposition to the […]

1 February 2019

Columbia, F-22A Raptor, Maduro, military intervention, no-fly zone, russia, S-300, SA-23, South America, Su-30MK2, US, Venezuela

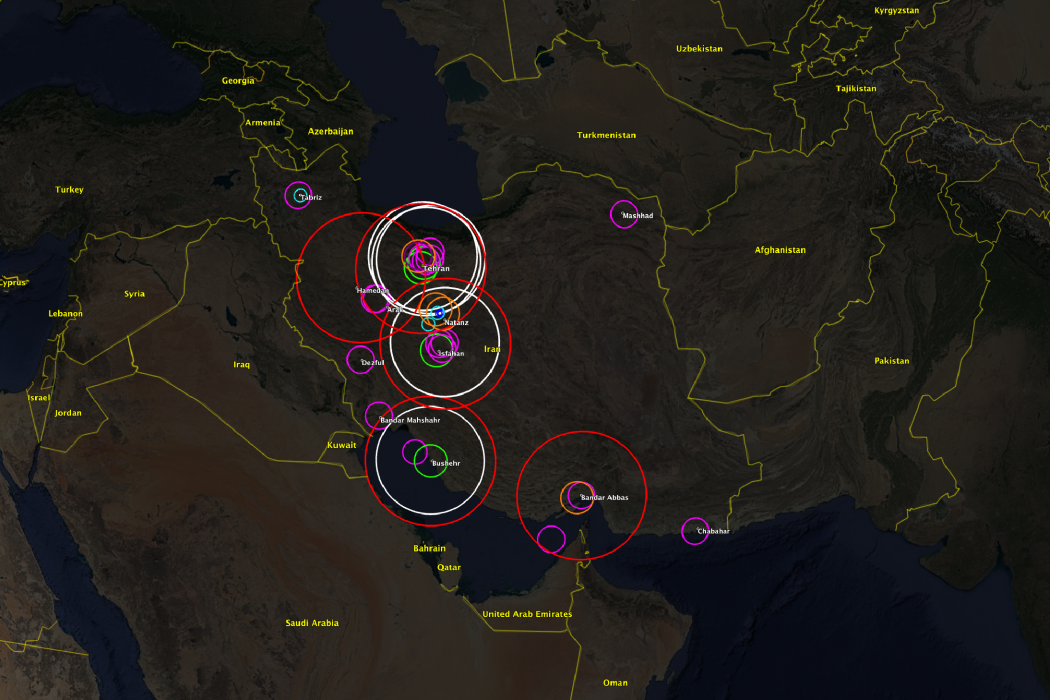

1. Over the last years, Iran has visibly improved its air defense (AD) systems by phasing in modern indigenous surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems. The Iranian SAM deployments primarily safeguard the regime as well as the nuclear and ballistic missiles (BM) programs. The protection of major population centers represents a secondary concern. Given the escalating tensions […]

5 December 2018

A2/AD, Iran, Iranian Air Defenses, IRGC, Middle East, S-300, SAM systems, Sayyad-2