Approximately one hundred men in Burkinabé black military uniforms attacked Karma village in Burkina Faso’s Nord region, killing more than 130 people and displacing countless others on 20 April 2023.

In the days following the incident, three main narratives regarding responsibility and motive for the attack have been gaining traction. Leveraging Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), our assessment examines these key narratives and prescribes responsibility for the attack.

For a brief look at our tradecraft and methodology, visit our Knowmad OSINT blog post that explains how we used OSINT to investigate the Karma massacre.

Disclaimer: viewer discretion is advised

KEY JUDGEMENTS

- Due to the large amount of authenticated imagery, eyewitness accounts, and converging evidence among diverse sources, we can confidently assess that the Burkinabé Army, and specifically one of the Battalion d’Intervention Rapide (BIR), is almost certainly responsible for the Karma massacre.

- We are highly confident that the growing trend of State-led civilian targeting which has intensified after the Traoré coup, is highly likely to persist over the next six months. The past actions, analysed massacre, climate of impunity, and this OSINT report findings sustain this claim.

- We are moderately confident that the alternative explanations of the massacre, such as a Paris-directed conspiracy or a jihadist false flag operation, remain unlikely. Easily refuted evidence and the absence of historical precedents constitute substantial weaknesses in these hypotheses.

COMPETING NARRATIVES

Three main narratives were identified in the aftermath of the massacre. According to the chronological order of appearance:

a. First narrative: According to international news agencies and human rights NGOs, the Burkinabé armed forces perpetrated the massacre against unarmed civilians in retaliation for an earlier Jihadist attack at an airfield near the village of Aoréma.

b. Second narrative: The Burkinabé military junta and its aligned media sources replied to the first narrative by discrediting the initial accusations and sustaining that the available information was not sufficient to identify the perpetrator.

c. Third narrative: Some Facebook and YouTube profiles spread the theory that French Special Operations Command coordinated a false flag operation aimed at smearing Burkina Faso in retaliation for the termination of Opération Sabre in January 2023.

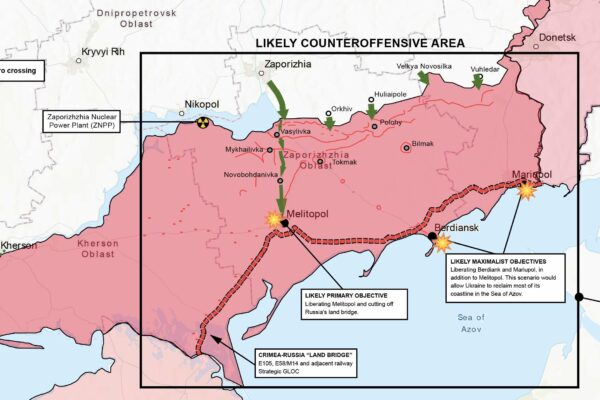

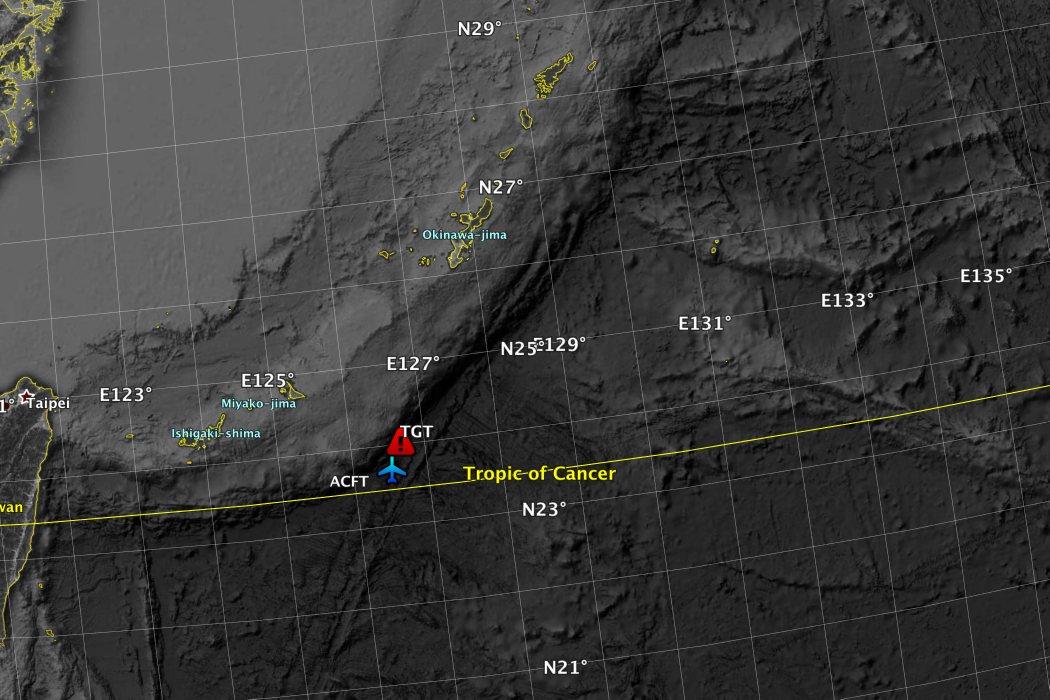

Assessed convoy route from Ouahigouya to Karma

FIRST NARRATIVE

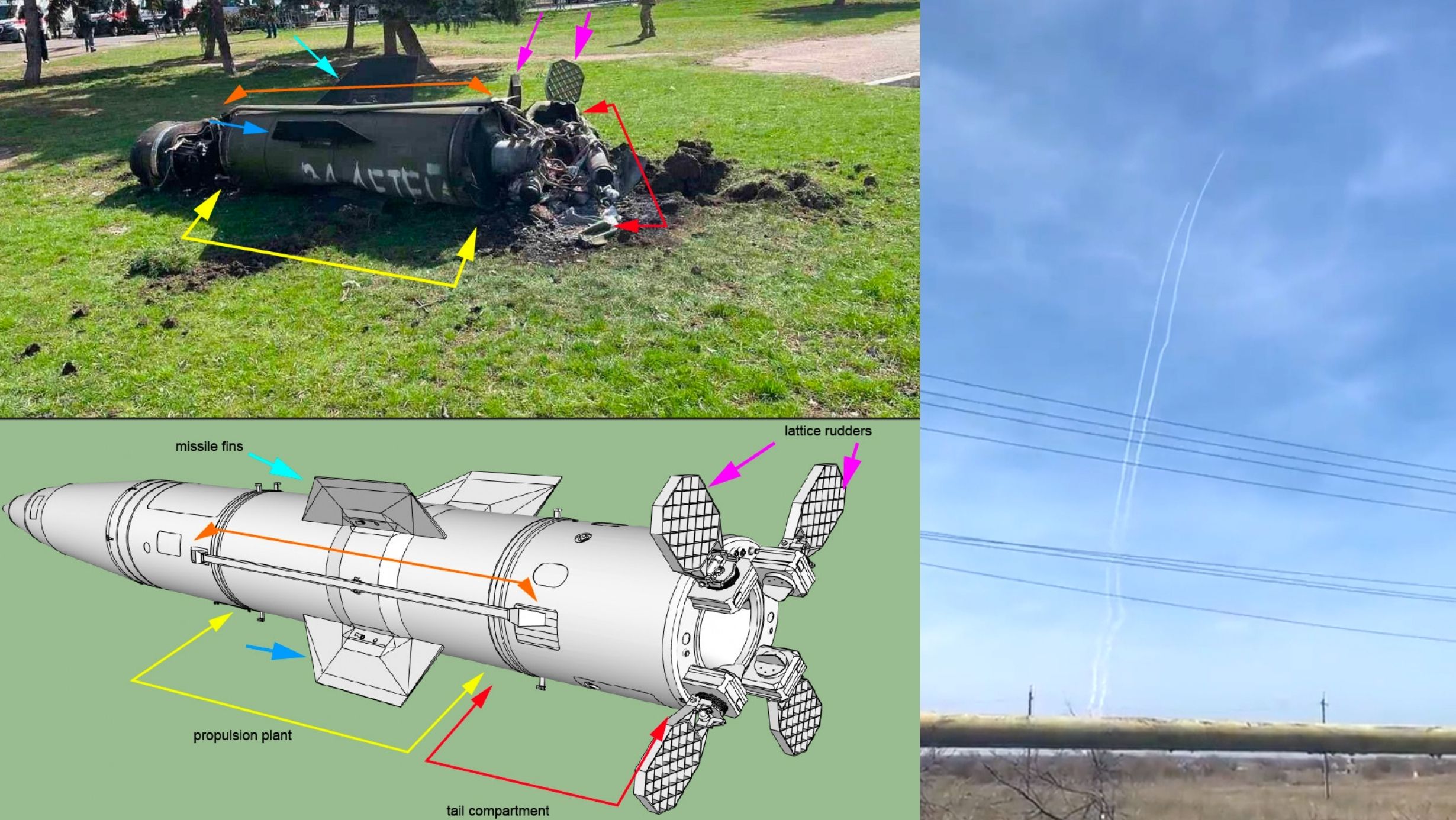

The massacre’s photographs are almost certainly authentic. After an extensive IMINT analysis and Reverse Image Search no editing was found and no similar photo appeared online before the massacre. The first narrative results are strengthened by this check given that the totality of the massacre’s pictures come from international media outlets.

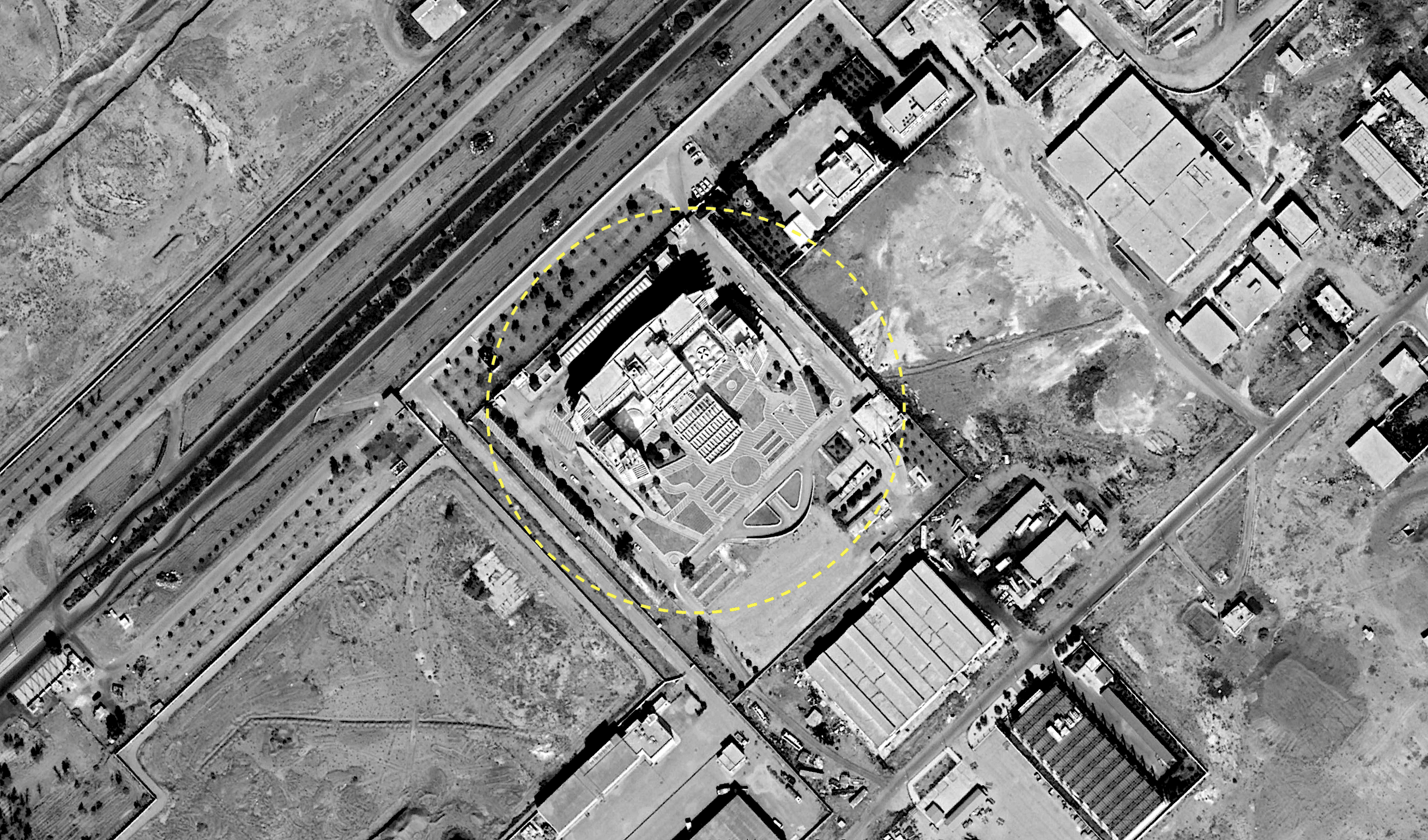

Geolocation confirms that the sites of the massacre was the village of Karma. The comparison between the available pictures and satellite imagery reveals a perfect match with the central mosque and a highly likely match for the massacre site. This finding further upheld the first narrative.

Geolocation of mosque in Karma using Google Earth Pro

Geolocation of bodies in Karma using Google Earth Pro

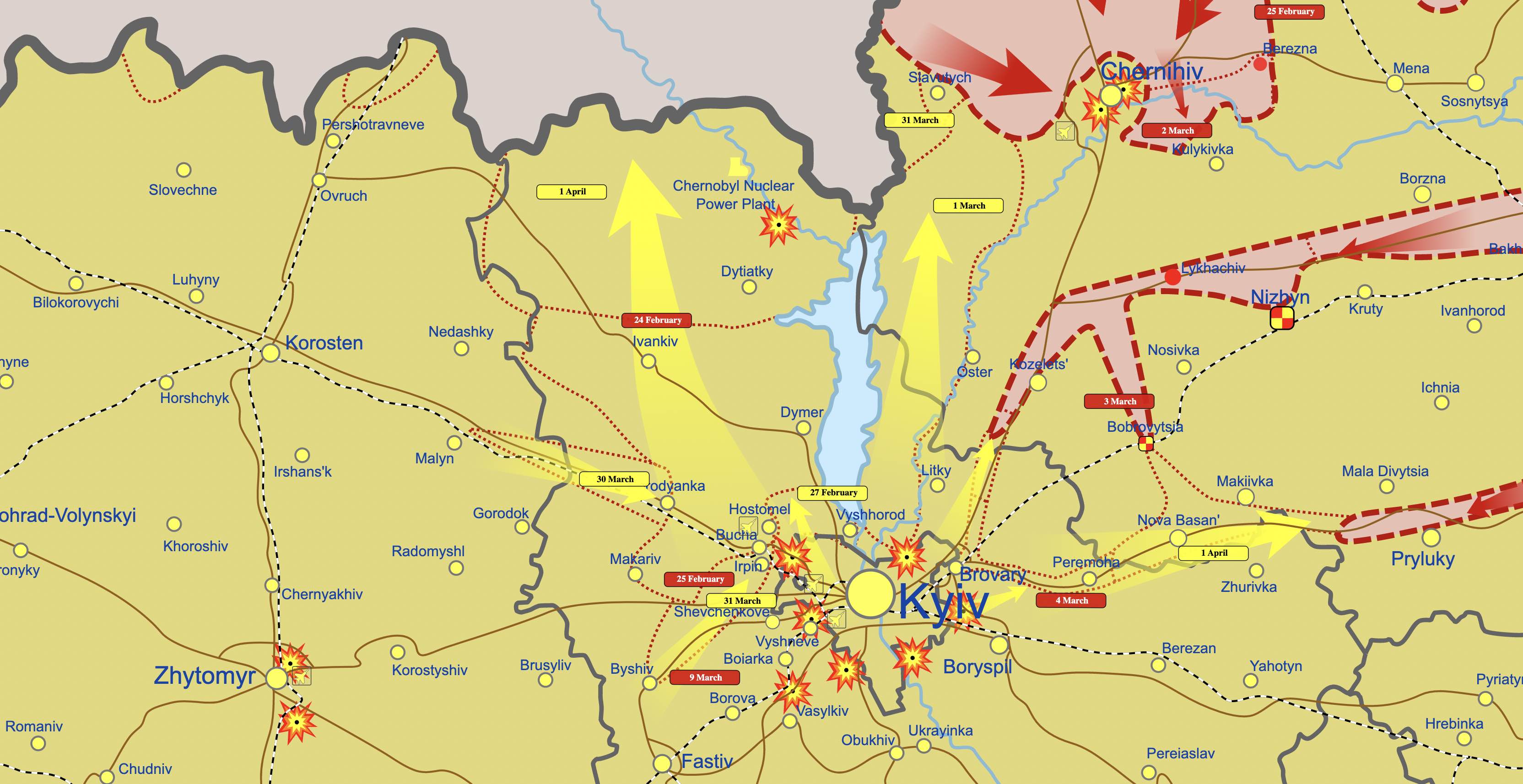

The first narrative temporal description is accurate. International media reported the passing of a military motorcycle column at dawn on 20 April (5:30-6:00 am local time) through the city of Ouahigouya. Considering the 24 km of paved and unpaved street linking Ouahigouya to Karma and an average speed of 30-40 km/h, the travel time is between 40 minutes and 1 hour and 25 minutes. The timeline is coherent with the reported beginning of the attack around 7:30 am.

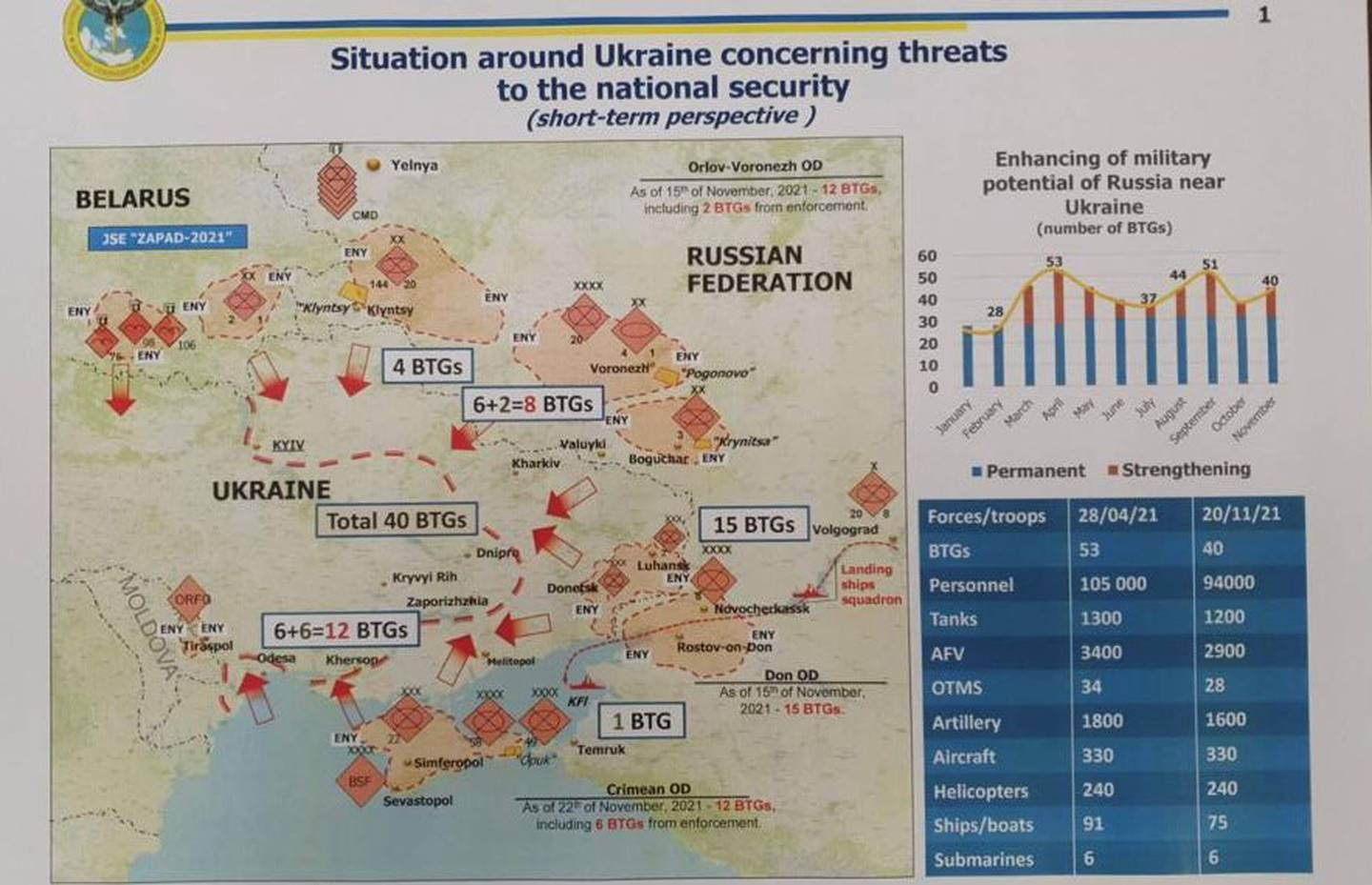

The GIS analysis of the ACLED database exposes a consolidated and upward trend of State Forces’ violence against civilians. Burkinabé State Forces are blatantly the most significant perpetrator accounting for almost 70 % of the events and more than half of the total fatalities concerning civilian targeting since 1997. Specifically, after the coup in September 2022 and the creation of the Battalions de Intervention Rapide (BIR) the following November, the exactions committed by Burkinabé Armed Forces rose markedly. In less than two years, the army perpetrated almost 40% of the civilian fatalities caused by State Forces since 1997.

SECOND NARRATIVE

Traoré’s skepticism regarding the army’s reasons for killing Burkinabé civilians is inconsistent with ACLED civilian targeting data. On multiple occasions State Forces killed civilians especially in the areas most affected by the insurgency, predominantly targeting ethnic minorities. Relatively ineffectual intelligence gathering and analysis processes on behalf of the Burkinabe forces complicate the identification of insurgents.

While it is true that insurgents came into possession of army material, Traoré’s suggestion of false flag attack by the insurgents remains highly unlikely. First, jihadist groups operating in Burkina Faso have often resorted to violence against civilians, thereby causing more than one third of the total civilian fatalities since 1997. Namely, the insurgents systematically engage in one-sided, indiscriminate violence against the local population. Second, the military column that attacked Karma was composed of roughly one hundred men. Organizing a false flag attack would require the theft of approximately one hundred uniforms and fifty army motorcycles from the newly formed BIR forces.

Despite Traoré’s promise of a formal enquiry, no update has yet been published yet. Military junta and Burkinabé media’s silence about the massacre, combined with the army blocking off access to Karma, compromise the transparency of the investigative process raising doubts on the effective willingness to avoid impunity.

THIRD NARRATIVE

The first posts suspecting a French involvement in the massacre appear only twelve days after the massacre. Whereas this does not directly confute this hypothesis, this inexplicable delay and its defensive/reactive attitude partially discredit it.

The images used in articles accusing France are out-of-context and mislead the reader. The image published by the Facebook page “INFOS DU FASO” was actually taken in southern Mali in 2016 and is publicly available through Wikicommons. Apart from the spelling mistake, the image posted by Abdoul de Rimka is a photo of the French army in Niamey (not Ayorou) from 29 June 2022.

Reverse Image Search (RIS) check of supposed evidence of French involvement

Another RIS check of supposed evidence of French involvement

One of the main sources of this narrative, Simon Paul Bangbo Ndobo, is almost certainly unreliable. The lack of any tangible evidence combined with his self-proclaimed “nomination by the Saint Spirit to the defense ministry of Africa” totally undermines the reliability of this source.

Screenshot of fringe conspiracy theorist from a video claiming that France was responsible for the attack

CONCLUSION

State-led violence on civilians is unfortunately not a novelty in Burkina Faso and the evidence regarding the Karma massacre further bolster this trend.

Although over three months have passed since the massacre, the enquiry committee has not yet published its findings on the carnage.

Based on available sources, we can confidently assess that the Burkinabé Army, specifically one of the BIR, is almost certainly responsible for the Karma massacre.

We will continue to monitor one-sided violence in Burkina Faso, publishing updates as new evidence emerges.

by Samuele Minelli Zufa and Christopher Dunn

Cover image copyright © D.R.

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 2]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TelSalman24.2.2018_optimized.png)

![Pride of Belarus: Baranovichi 61st Fighter Air Base [GEOINT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/cover_article.jpg)

![This is How Iran Bombed Saudi Arabia [PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/map4cover-01-compressor.png)

![Evacuation “Shattered Glass”: The US/ Coalition Bases in Syria [Part 1]](https://t-intell.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/KLZJan.62018copy_optimized.png)