Snake Island, or Serpents Island (Ostriv Zmiinyi in Ukrainian; Insula Serpilor in Romanian) is an islet off Ukraine’s southwestern coast and near the Danube Delta in the Black Sea. With a surface of 17 ha, the islet became a major flashpoint between the Ukrainian Operational Command-South and the Russian Navy, following the Russian seizure of […]

Posts Tagged

‘Bayraktar’

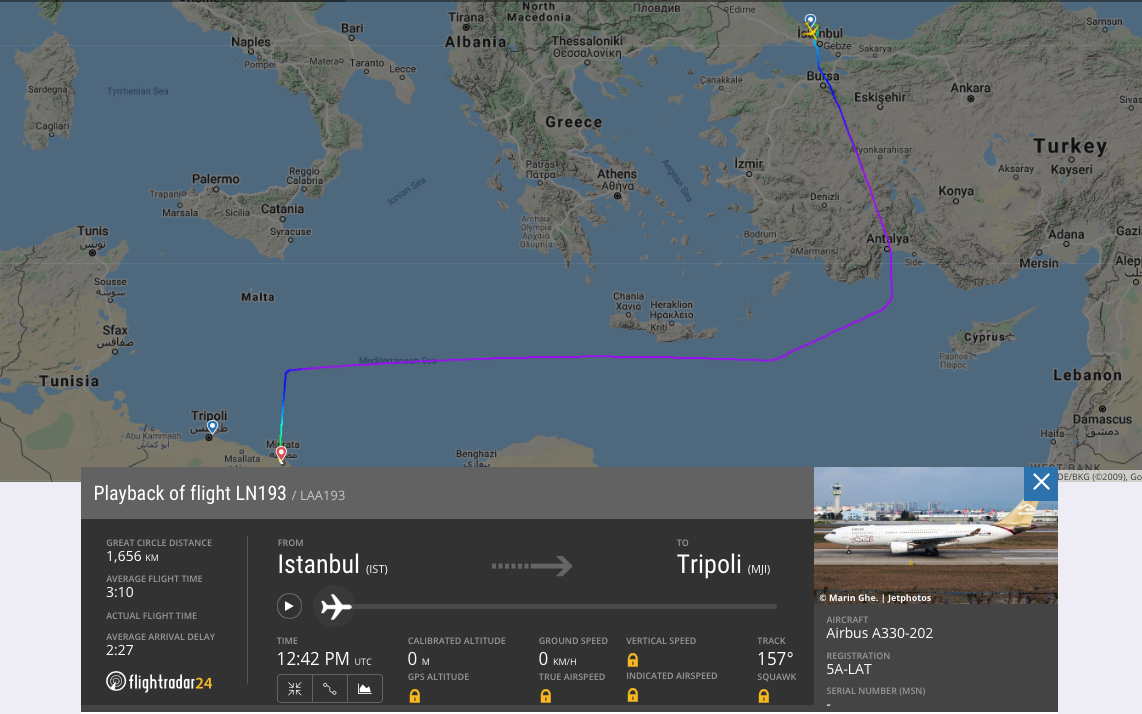

Mounting evidence shows that Turkey is deploying “Syrian National Army” (SNA) militiamen to Libya by using commercial airlines. In December 2019, major media outlets broke the news that Ankara plans to send SNA militants to reinforce the “Government of National Accord” (GNA). Since then, there has been a growing number of indicators and reports that […]

18 January 2020

AeroTransCargo, air-bridge, Bayraktar, GNA, Haftar, Libya, Libya Airlines, Libyan Air, Libyan Civil War, LNA, Mitiga, Qatar, SNA, Syrian Rebels, Tripoli, turkey, UAE, UCAV