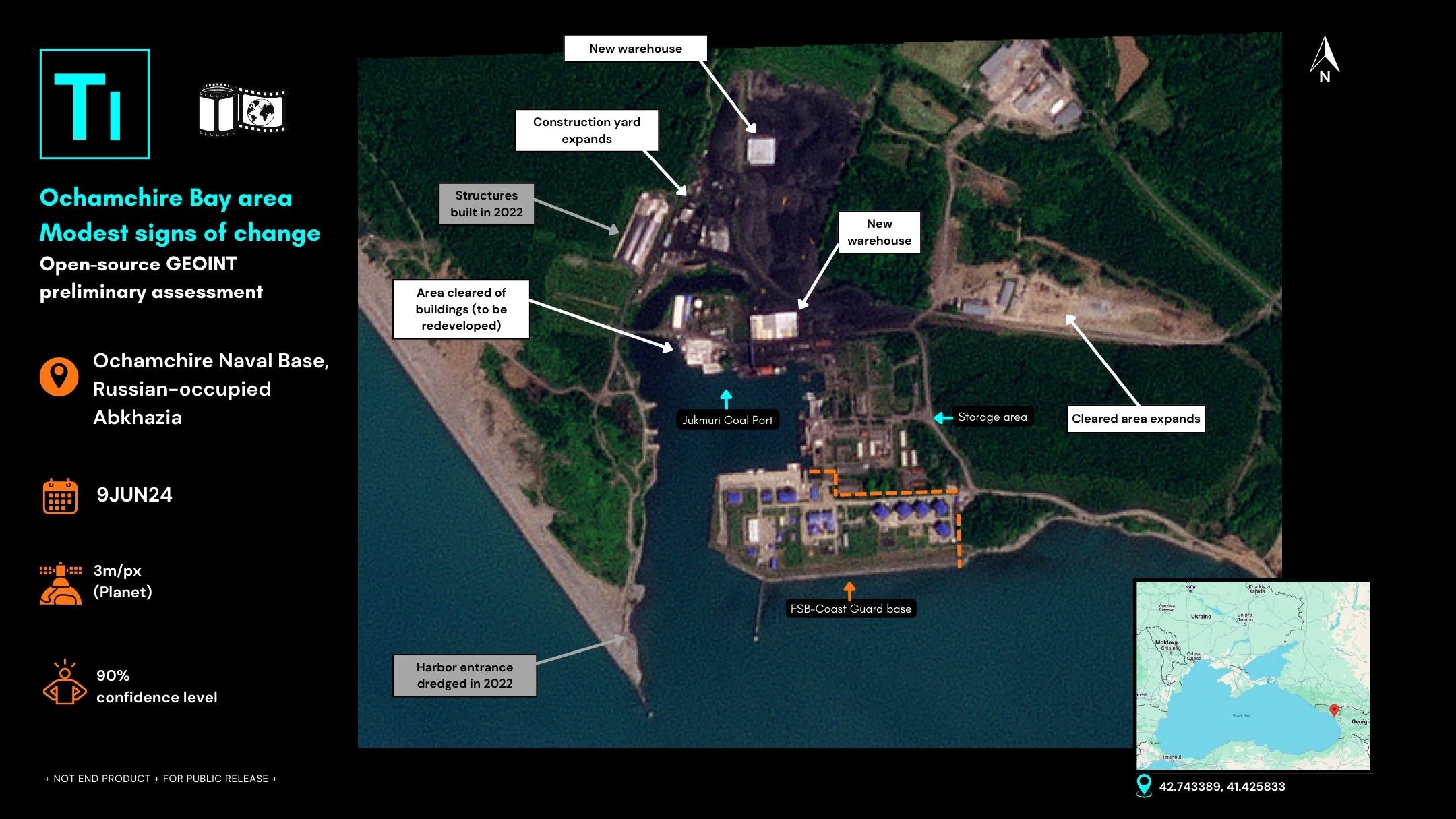

Signs of infrastructure expansion in Ochamchire Bay, Russian-occupied Abkhazia, are emerging. While no major developments occurred at the pre-existing Russian FSB-Coast Guard base, new warehouses and cleared land in the adjacent area suggest potential expansion in connection to the Kremlin’s plans. Ochamchrie could serve as a reserve base for Russian warships displaced from occupied Crimea […]

Posts Tagged

‘Black Sea’

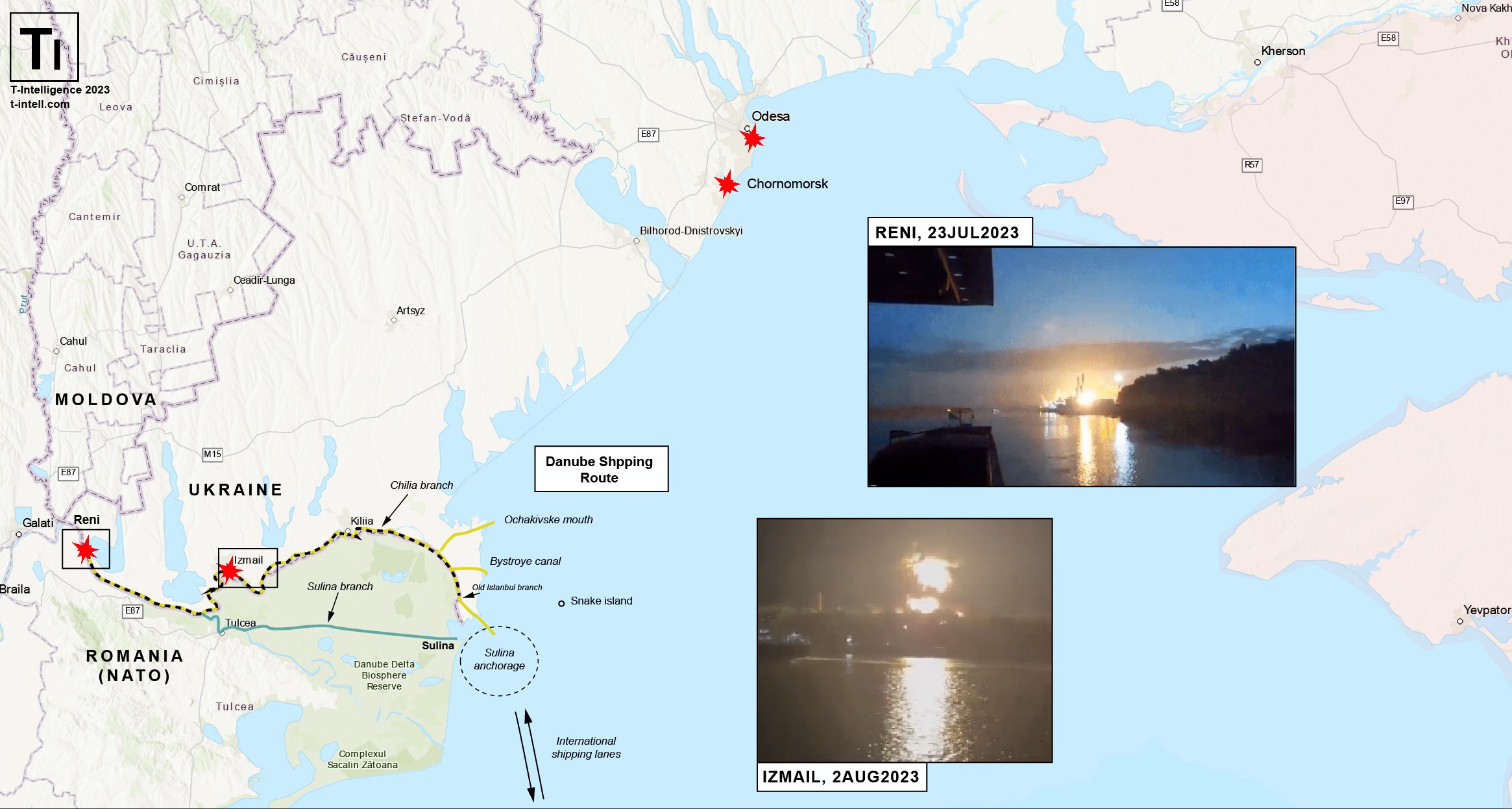

KEY JUDGEMENTS Russia’s missile and drone attacks against Reni and Izmail marked the first strikes on Ukraine’s Danube ports since the full-scale invasion began on 24 February 2022. The attacks are part of a new Russian campaign to degrade Ukraine’s ability to export agricultural goods and destroy grain stocks. They also seek to deter merchant […]

Snake Island, or Serpents Island (Ostriv Zmiinyi in Ukrainian; Insula Serpilor in Romanian) is an islet off Ukraine’s southwestern coast and near the Danube Delta in the Black Sea. With a surface of 17 ha, the islet became a major flashpoint between the Ukrainian Operational Command-South and the Russian Navy, following the Russian seizure of […]

Last week, the Black Sea became the latest theatre upon which tensions flared between the United Kingdom and Russia. On June 23, the British Royal Navy’s Type-45 HMS Defender entered contested waters off the Crimean Peninsula while sailing from Odessa (Ukraine) to Batumi (Georgia). As expected, Russia reacted aggressively, sending fighter jets and warships to […]

5 July 2021

Black Sea, Crimea, HMS Defender, Royal Navy, russia, Sea Breeze 21, UK, Ukraine

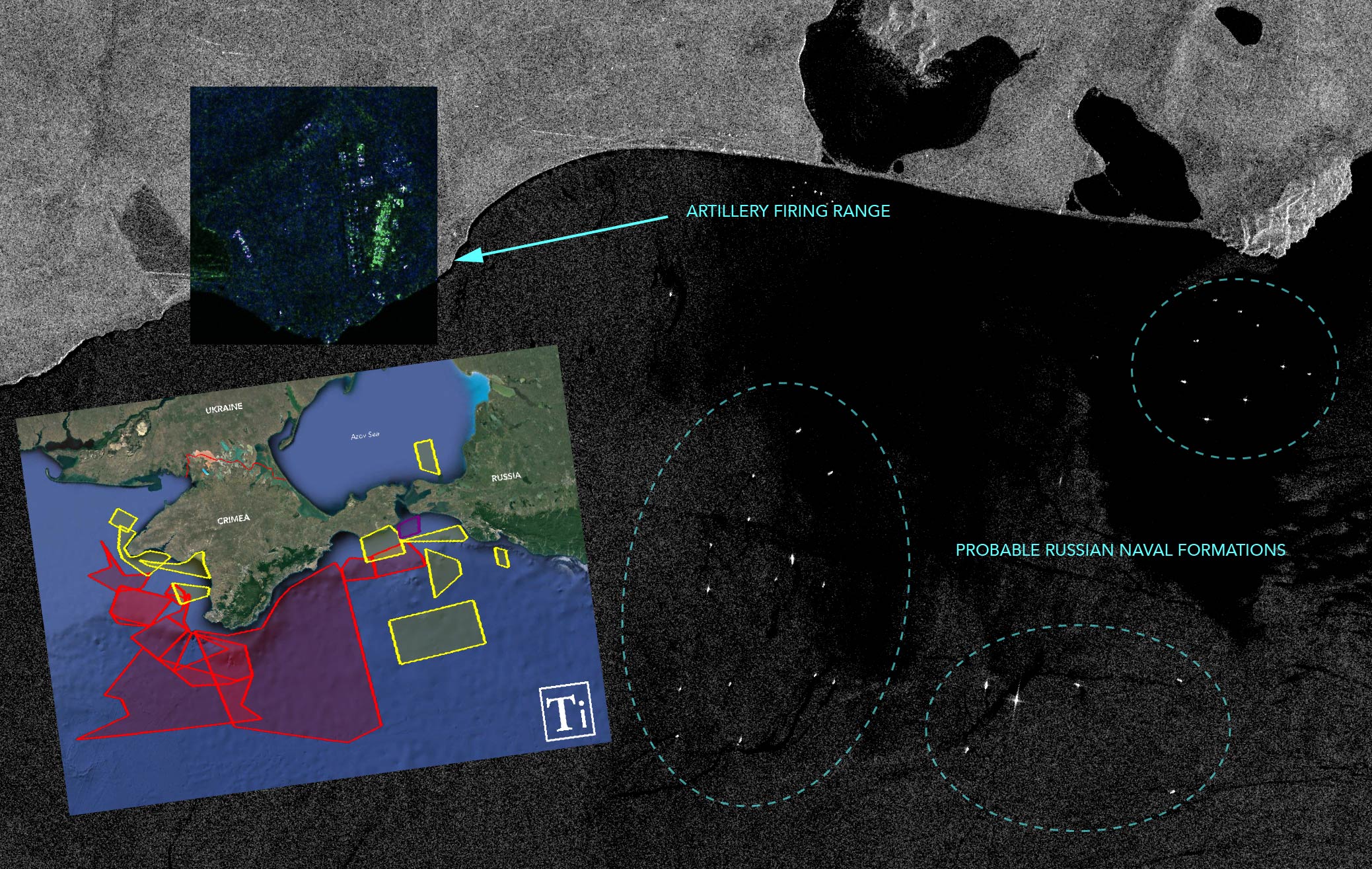

Russia has concentrated warships from all fleets, except the Pacific fleet, in the Black Sea for joint drills. While not unprecedented, it is rare to see such a show of force. The cross-theater deployments and large-scale exercises bear the hallmarks of a maritime build-up intended to intimidate Ukraine and deter NATO activities in the Black […]

20 April 2021

Black Sea, Crimea, military exercise, NATO, OSINT, russia, Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine

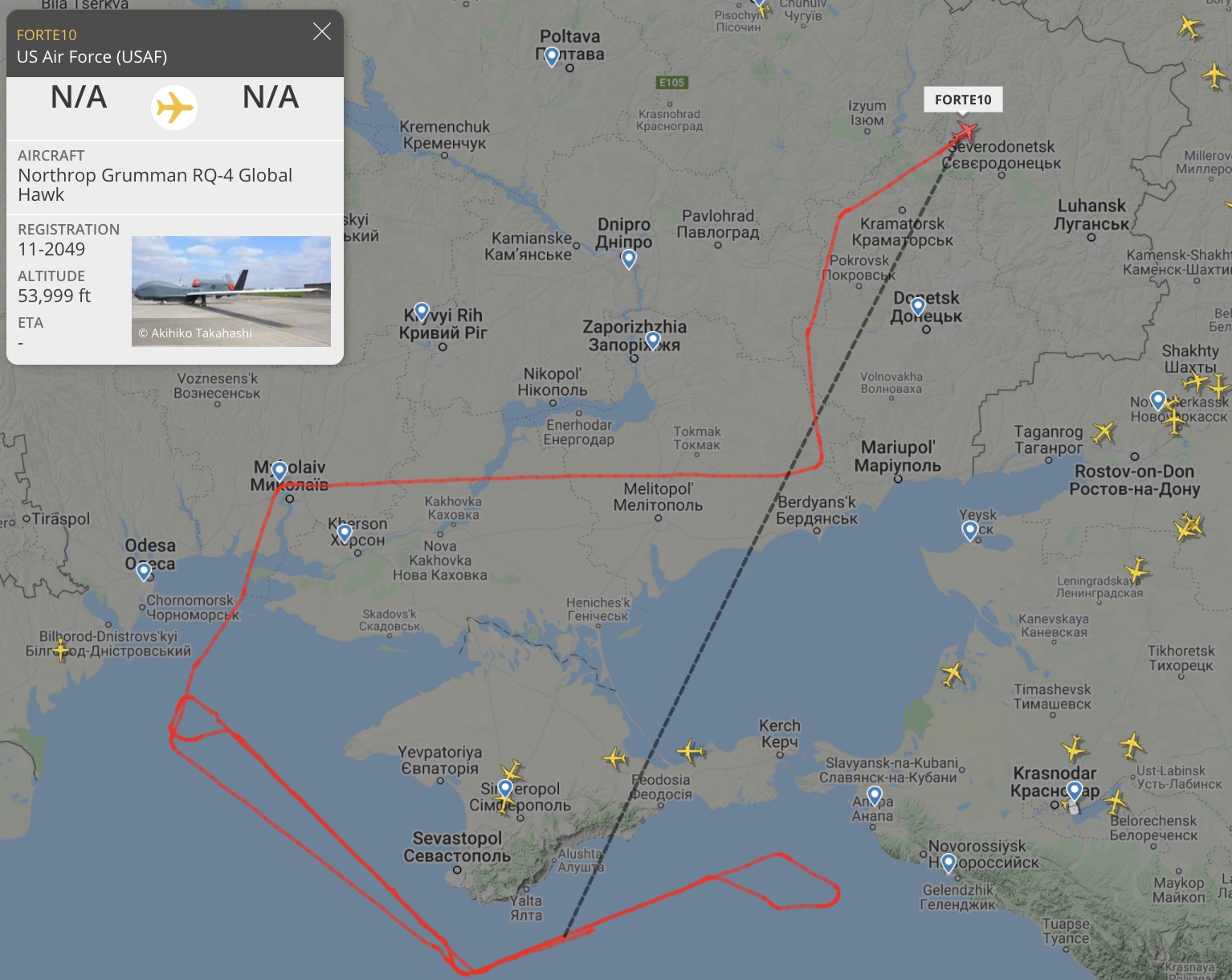

U.S. and British reconnaissance aircraft are intensively monitoring eastern Ukraine, Crimea, and Russia’s Black Sea coast amid fears of a renewed Russian offensive. RUSSIA’S 2021 BEAR SCARE In the past month, Russia has moved over 14,000 soldiers and a vast array of capabilities, including Iskander ballistic missiles, tanks, howitzers, and thermobaric rocket launchers towards the Ukrainian border. […]

The United States Air Force (USAF) will deploy MQ-9 Reaper drones to the 71st Air Base in Campia Turzii (Cluj county), Romania. The mission, starting in January 2020, has been fully coordinated with the Romanian government. Directed by the U.S. European Command’s air component, the deployment serves to promote stability and security within the region, and […]

22 January 2020

71st Campia Turzii, Air Force, Black Sea, drone, MQ-9 Reaper, Qassim Soleimani, Romania, russia, UAV

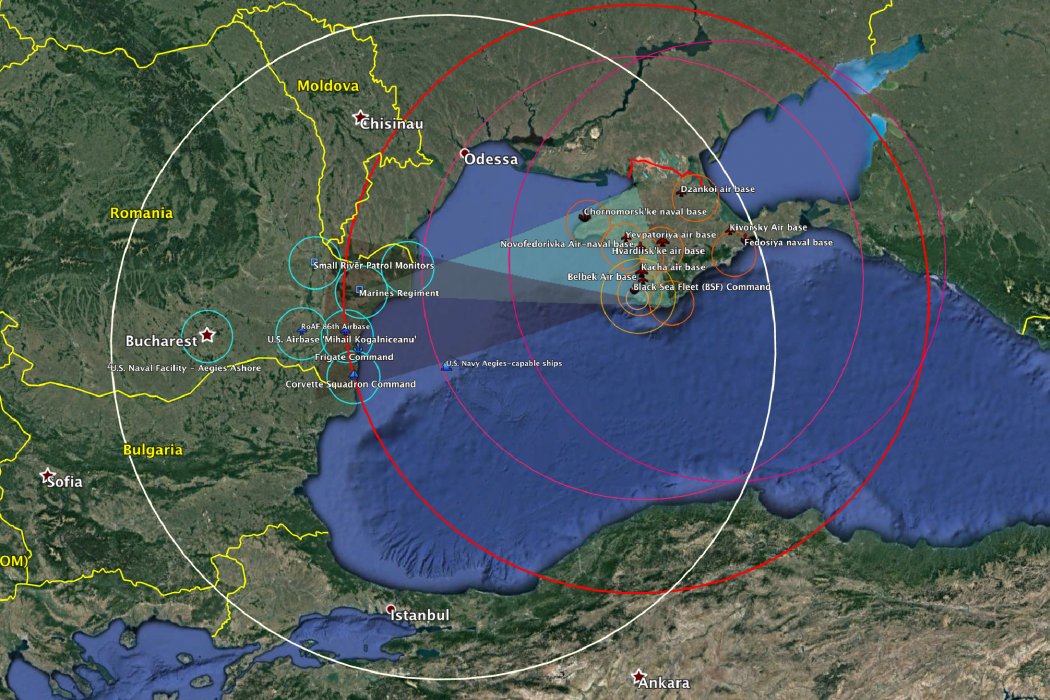

Russia continues the wholesale militarization of the Crimea peninsula with the upcoming deployment of nuclear-capable long-range Tu-22M3 bombers (NATO reporting name: Backfire-C) to Hvardiyske/Gvardeyskoye air base. The airfield’s large aircraft revetments and logistics facilities can host at least 20 Backfires. With the Backfire eyed as a future launching platform for the Kinzhal hypersonic aero-ballistic missile, […]

1. Satellite imagery shows several Kh-47 “Kinzhal” hypersonic aeroballistic missiles (NATO reporting name unavailable) next to Russian Aerospace Forces (RuAF) MiG-31K fighter jets (NATO reporting name: “Foxhound”) on the apron of the RuAF’s 929th State Flight Test Center (STFTC) in Akhtubinsk, Astrakhan oblast (Russia). The Kinzhals appear on Digital Globe images dating from September 3, […]

12 February 2019

Akhtubinsk, Black Sea, Caspian Sea, Foxhound, hypersonic missile, IMINT, Kinzhal, MiG-31K, russia, Russian Aerospace Forces

In 2017, Romania initiated a visionary defence procurement program that will reinforce NATO’s Eastern flank and make the Romanian military a leading force in the Black Sea by the early 2020s. The $11.6 billion shopping list includes top-of-the-line products such as Raytheon’s latest Patriot air defense system. The assets are specifically tailored to counter the Russian […]