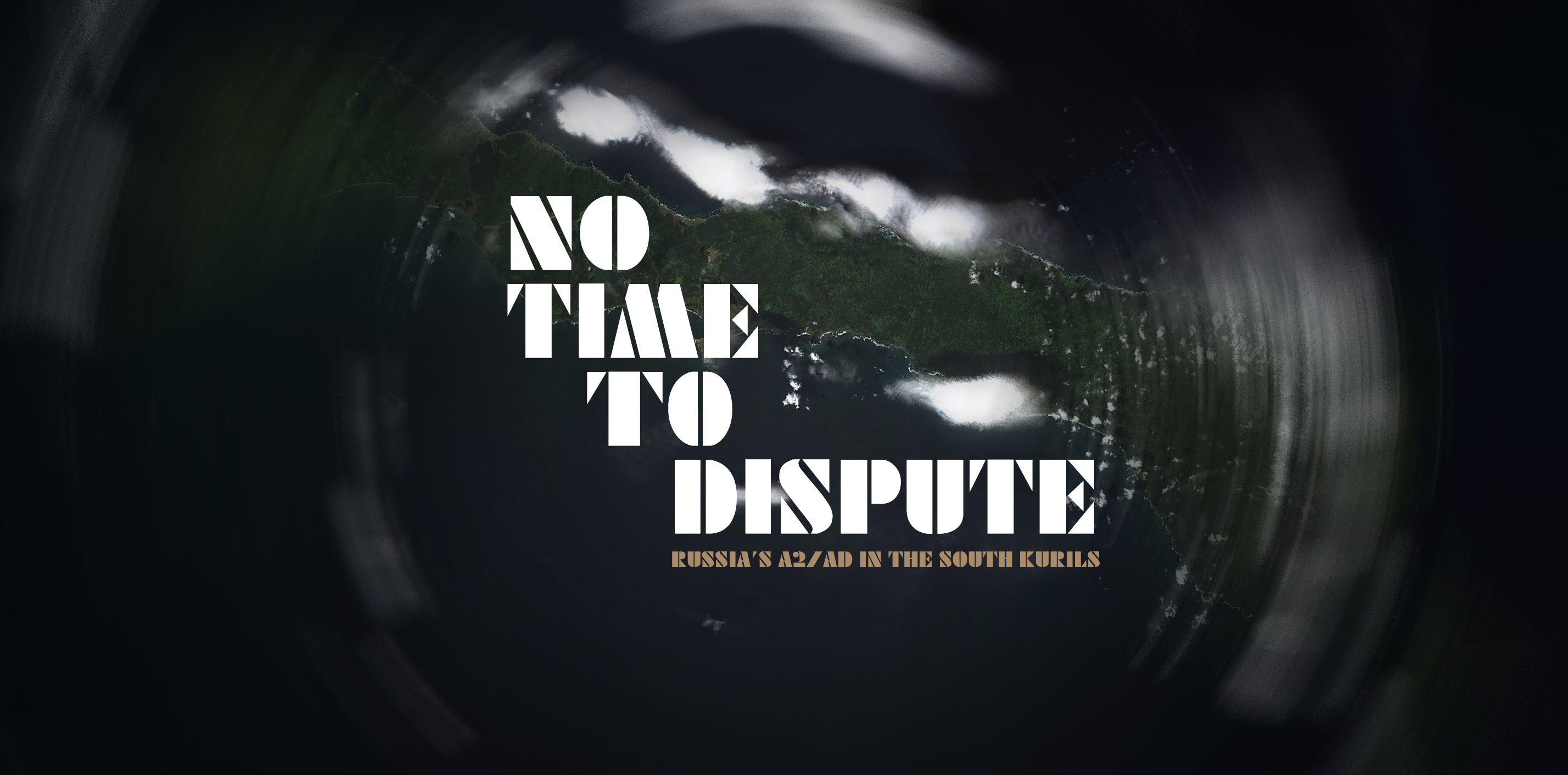

Remote and derelict, riddled with active volcanoes and disputed between Russia and Japan, the South Kurils make the perfect secret lair for any self-respecting evil genius. It’s no wonder the writers behind No Time to Die, the latest Bond film, chose the South Kurils as the setting for the film’s final act. While not directly […]

Posts Tagged

‘A2/AD’

The Polish government has signed a contract with Lockheed Martin to buy 32 F-35A stealth multirole fighter jets for the Polish Air Force, on January 31, 2020. The contract is estimated to be worth $4.6 billion, making it the biggest military purchase in the country’s history. The first F-35As are expected to arrive in Poland […]

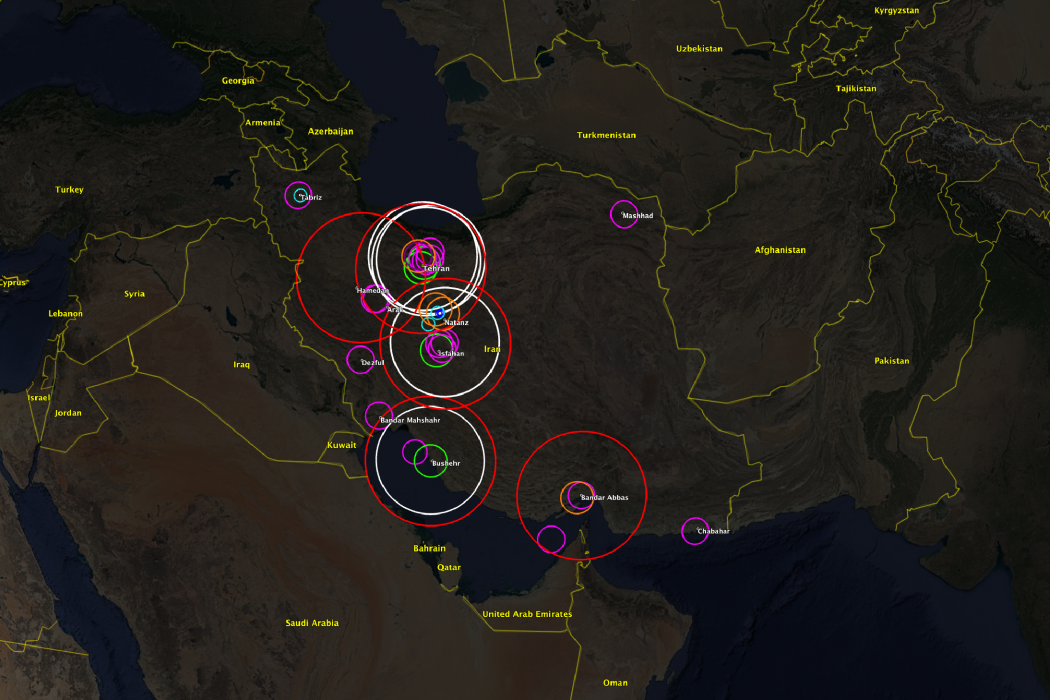

1. Over the last years, Iran has visibly improved its air defense (AD) systems by phasing in modern indigenous surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems. The Iranian SAM deployments primarily safeguard the regime as well as the nuclear and ballistic missiles (BM) programs. The protection of major population centers represents a secondary concern. Given the escalating tensions […]

5 December 2018

A2/AD, Iran, Iranian Air Defenses, IRGC, Middle East, S-300, SAM systems, Sayyad-2

In 2017, Romania initiated a visionary defence procurement program that will reinforce NATO’s Eastern flank and make the Romanian military a leading force in the Black Sea by the early 2020s. The $11.6 billion shopping list includes top-of-the-line products such as Raytheon’s latest Patriot air defense system. The assets are specifically tailored to counter the Russian […]

Strategic Analysis (20 min read) – The Syrian quagmire is nearing the end. The Assad regime is quasi-victorious with more than half of the national territory regained and over 75% of the Syrian population under its control. The Opposition forces are utterly degraded and boxed into a few isolated patches of land in the western […]

10 January 2018

A2/AD, Cold War 2, isis, Latakia, Mediterranean Sea, Moscow, NATO, permanent presence in Syria, Rebels, russia, Russian air strikes, syria, Syrian Civil War, Tartus