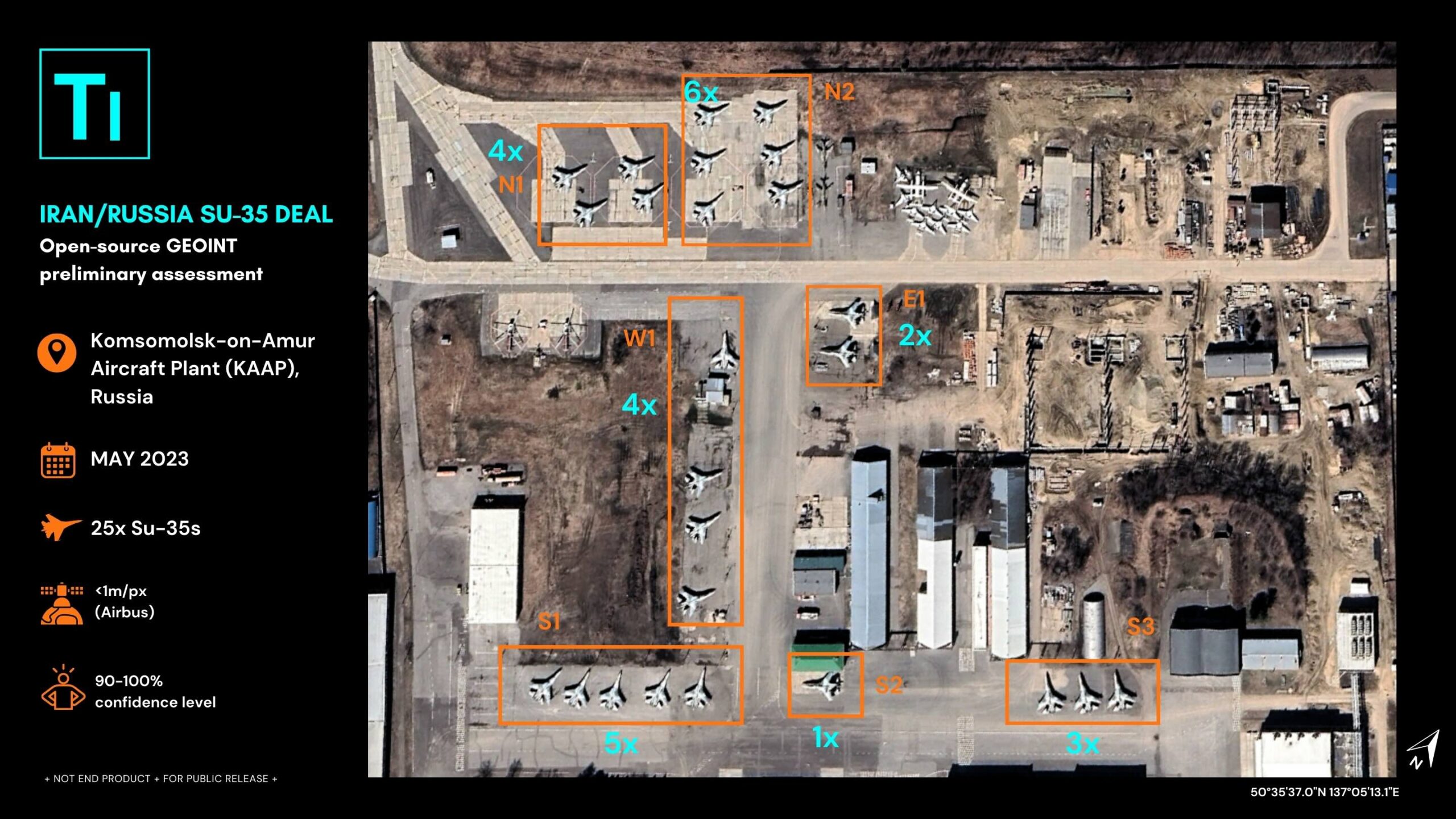

Iran has finalized a deal to acquire Su-35 fighter aircraft, the batch initially rejected by Egypt, from Russia, according to Iranian officials on 28 November 2023. Current data, up to 28OCT2023, shows 25 Su-35SE air superiority jets (AFIC/NATO reporting name: Flanker-E) still stationed at the Komsomolsk-on-Amur Aircraft Plant (KAAP) in Russia, with deliveries anticipated in […]

Posts Tagged

‘Middle East’

1. The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) have initiated Operation Northern Shield to identify and destroy Hezbollah cross-border tunnels in Northern Israel. At the moment, the IDF is operating exclusively on Israeli soil and has shown little intent to expand its operations across the Lebanese border. However, Jerusalem’s growing distrust of the United Nations Interim Force […]

16 December 2018

Galilee, Golan Heights, Hezbollah, Iran, IRGC, Israel, Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), Israeli-Iranian Shadow War, Lebanon, Middle East, Operation Northern Shield, syria, tunnels

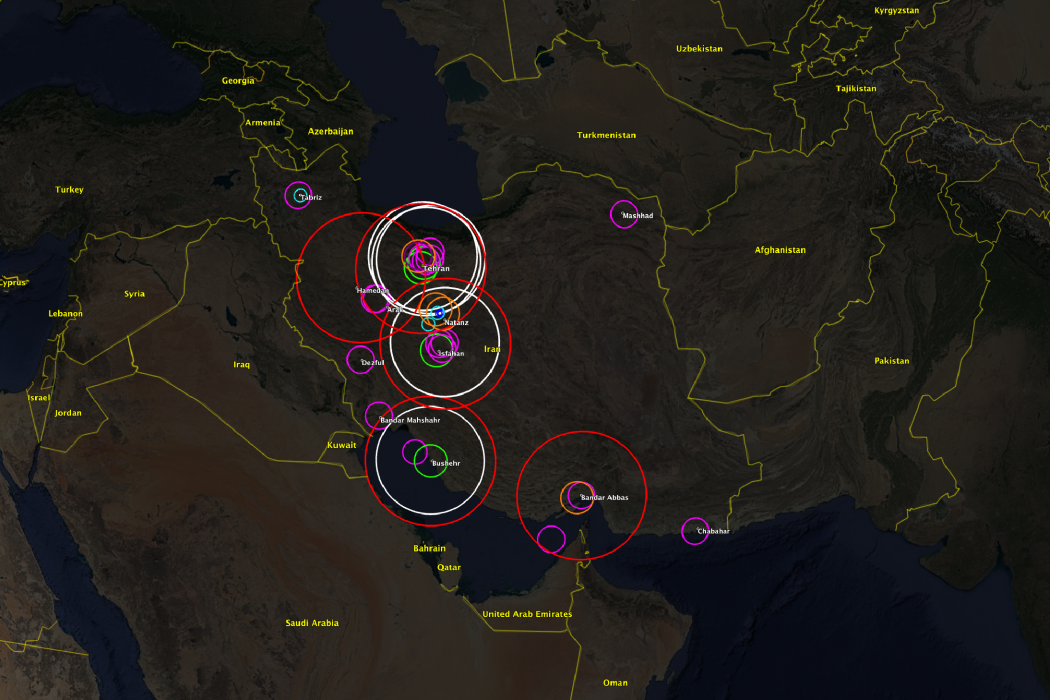

1. Over the last years, Iran has visibly improved its air defense (AD) systems by phasing in modern indigenous surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems. The Iranian SAM deployments primarily safeguard the regime as well as the nuclear and ballistic missiles (BM) programs. The protection of major population centers represents a secondary concern. Given the escalating tensions […]

5 December 2018

A2/AD, Iran, Iranian Air Defenses, IRGC, Middle East, S-300, SAM systems, Sayyad-2

1. NATO has agreed to organize a military training mission in Iraq to project stability in the Middle East – Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg announced on Thursday following the North Atlantic Council (NAC) assembly of the Ministries of Defense gathered in Brussels. The project was considered the government from Baghdad and Prime-Minister Abadi sent an official request […]

16 February 2018

Counter-terrorism, iraq, Iraqi Security Forces, Middle East, NATO, non-combatant, training mission

Situation Report – After 3 years of ISIS occupation, Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul, has been completely liberated. The 9-months long battle saw Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) alongside allies, Shi’a PMU and the U.S.-led Coalition fighting their way block-to-block from the rigged, mined bridges of East Mosul, to the Euphrates river crossing of early 2017, […]

10 July 2017

Abadi, after ISIS, al-Baghdadi, al-Nuri mosque, Al-Qaeda in Iraq, anti-terror, Baghdad, CENTCOM, falls, Iran, iraq, Iraqi Security Forces, isis, Islamic State of Iraq, Kurds, Middle East, Mosul, Niniveh, Salafism, Tel Afar, US, US-led Coalition

T-Intelligence presents the daily journal for Raqqa. This space will contain (hopefully) daily entries regarding the developments in the battle for Raqqa, yet time gaps may very as this project depends not only on what happens in the field but also on what amount of data (quantity, quality, credibility) surfaces online. Methodology and Objectives From […]

SITUATION REPORT – The Houthis (Arabic: الحوثيون al-Ḥūthiyyūn ; officially called Ansar Allah أنصار الله “Supporters of God”) and Saleh Ali al-Sammad’s Supreme Political Council in Yemen have claimed that a ballistic missile hit a military target near Saudi Arabia’s capital Riyadh – a communique released yesterday by Houthi affiliated media informs, as sighted by […]

6 February 2017

Decisive Storm, Emirati soldiers, Hadi, Houthi, humanitarian crisis, Immigration, Iran, Iranian aid, Iranian Regional Activities, isis, Middle East, Qatar, Red Sea, Riyadh, Saleh, Saudi air strikes, Saudi Arabia, Teheran, United Arab Emirates, US, USS Cole, Yemen

The following is an operational review focused on Operation Euphrates Shield, launched, coordinated by the Turkish Armed Forces and spearheaded by the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and allies. Preface On 24th July 2016, limited Turkish tanks assets alongside Special Operators have passed the border into Syria, also assisting hundreds of Free Syrian Army (FSA) rebels […]

5 September 2016

Aleppo, Ankara, anti-ISIS operation, assad, Da'esh, Erdogan, failed Coup, Incirlik air base, isis, Jarabulus, Middle East, Operation Euphrates Shield, Rojava, Syria Civil War, Turkey invades Syria, Turkey's safe zone, USA, YPG

Following Jabhat al-Nusra’s decision to split from the main Al-Qaeda structure with mutual acceptance, this descriptive analysis explores the organization’s history and its motives of this decision. It also considers prospective outcomes, taking into account all the major inputs of the regional and local chessboard as well as the geopolitical array.