The Iraqi Parliament has voted to expel US and Coalition forces from Iraq. The draft resolution will force the Iraqi Government to cancel the request of assistance submitted to the Coalition in 2014 to fight ISIS. If enacted, the resolution will force all foreign forces participating in the Coalition against ISIS to leave Iraq permanently […]

Posts Tagged

‘Baghdad’

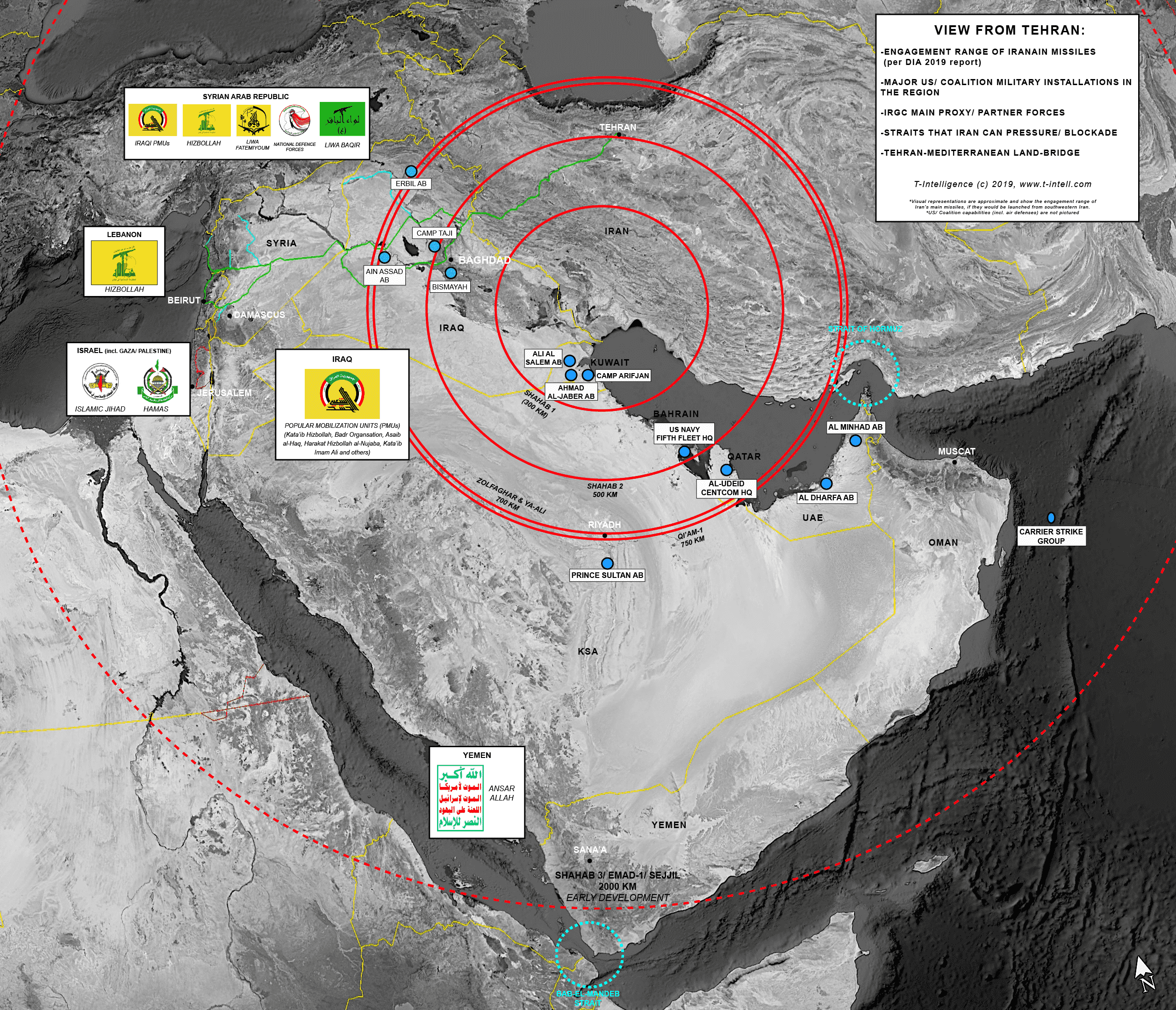

After the US airstrike that killed General Suleimani, Iranian retaliation is very likely, but not guaranteed. Given the magnitude of the US response to the Embassy attack in Baghdad, Tehran is likely exploring ways to retaliate without overplaying its hand. Iran can either use its own personnel (IRGC or Artesh) or proxy forces (in Lebanon, […]

4 January 2020

Baghdad, Iran, Iranian Regional Activities, iraq, IRGC, Qassim Soleimani, retaliation

IRGC-Quds Force Commander, General Qasim Soleimani, and Kata’ib Hizbollah (KH) Commander/PMU Deputy Chairman, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, were killed in a US airstrike in Baghdad International Airport. The targets are confirmed killed by all sources. Soleimani and his associates were planning to attack and kidnap American diplomats in Iraq. This is the biggest targeted killing operation […]

3 January 2020

air strike, al-Muhands, Baghdad, Iran, Iranian Regional Activities, iraq, IRGC, Kata'ib Hizbollah, PMU, Qasim Soleimani, Quds-Force

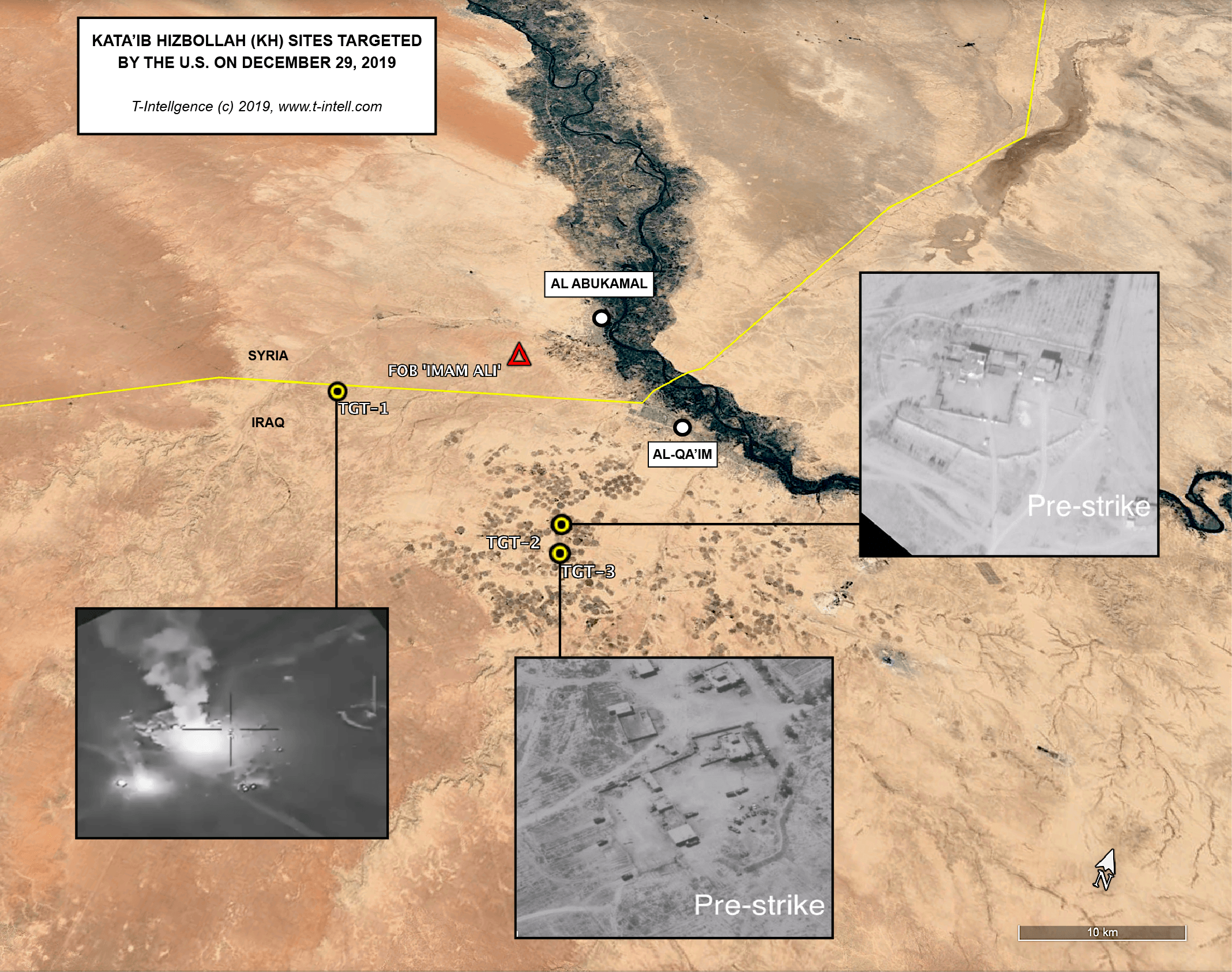

The American air strikes against Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH), one of the strongest Iraqi Shiite militias, on 29 December are a “game-changer.” The strikes prove that the United States is finally willing to retaliate militarily against Iran’s covert aggression. While the kinetic retribution will instate some degree of deterrence, Washington will likely remain passive towards Iranian […]

31 December 2019

al-Qaim, Badr Organization, Baghdad, Iran, Iranian Regional Activities, iraq, IRGC, ISF, isis, Kata'ib Hizbollah, land-bridge, Shiite Crescent, Special Groups, Tehran, US

Situation Report – After 3 years of ISIS occupation, Iraq’s second largest city, Mosul, has been completely liberated. The 9-months long battle saw Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) alongside allies, Shi’a PMU and the U.S.-led Coalition fighting their way block-to-block from the rigged, mined bridges of East Mosul, to the Euphrates river crossing of early 2017, […]

10 July 2017

Abadi, after ISIS, al-Baghdadi, al-Nuri mosque, Al-Qaeda in Iraq, anti-terror, Baghdad, CENTCOM, falls, Iran, iraq, Iraqi Security Forces, isis, Islamic State of Iraq, Kurds, Middle East, Mosul, Niniveh, Salafism, Tel Afar, US, US-led Coalition

SITUATION REPORT – A video appeared online supposedly showing a military build-up in the Turkish southeastern region of Hakkari, near the Iraqi border. The convoy is formed by dozens of vehicles; the number may even reach a hundred.

5 January 2017

Ankara, Arrests in turkey, Assault on Mosul, Baghdad, Barzani, Hakkari, iraq, Irbil, Kurdistan, Mosul, Pashmerga, PKK, Terrorism, turkey, Turkish forces in Iraq